Postliberals are assembling reading lists. In contravention perhaps of a basic precept held by many conservative thinkers—the idea, namely, that conservatism is not, in fact, an ideology and cannot plausibly be theorised about at all—postliberals are compiling a canon. The canon includes a lot of explicit conservatives. It is made up, in the main, however, of the merely conservative-minded: repentant Marxists, disenchanted liberals, and Christians who oppose the moral relativism and materialism of secular capitalist society.

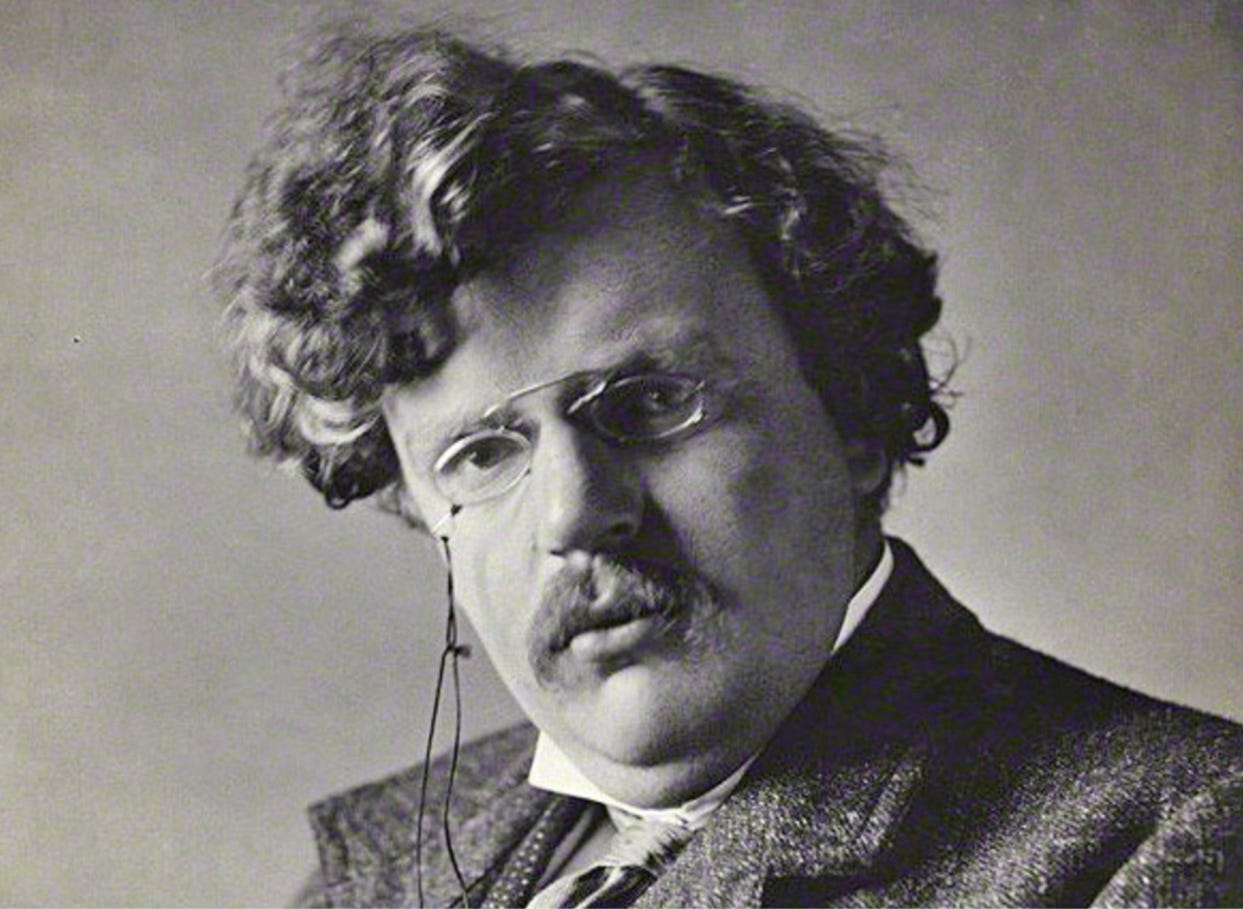

So far, though, it is seriously incomplete. Yet, there is one omission, which, above all, stands out: the absence of the philosopher, lay theologian, and critic, G. K. Chesterton (1874-1936). For just as much as Christopher Lasch or Simone Weil, both extraordinary prophets and prognosticators and, for that reason, postliberal favourites, Chesterton is a thinker for our time. More, he shows us, at a moment of existential crisis, concretely, how we must live.

Chesterton was not a conservative. Certainly, he regarded an overly zealous commitment to reason as tantamount to madness and he believed in conservation and tradition. But conservatives, in his view, were guilty of conserving all the wrong things. Failing to account for the natural tendency of things to get worse, they were guilty, most importantly, of defending capitalism, an insane and nefarious economic and political system with relatively shallow and uneven historical roots. To be truly conservative one needed a long view and one could not eschew revolution.

Notwithstanding the associations his name evokes, Chesterton was a self-proclaimed liberal. A fierce democrat, he believed that the most important things in life ought to be left to ordinary people themselves. He did not, however, believe in the hidden hand of the market, as other liberals did. Like parliamentary politics, private enterprise was a sham, he maintained. Economic Man was capable only of creating monopoly.

To take the liberty of describing his political position for him: Chesterton was a reactionary. Situating himself between “the two extremes” of capitalism and communism, he advocated a policy of “small distributed property” (distributism), akin to what was typical, he held—rightly or wrongly—during the European Middle Ages. In short, according to Chesterton, we must become peasants again.

Writing in 1926, amidst the General Strike in Britain, Chesterton argued that capitalism represented a “danger” and was rapidly becoming a “death-trap.” The very label “capitalism” was indeed a misnomer since the use of capital was far from peculiar to the system of capitalist production. A far more accurate appellation would be “proletarianism,” he claimed because what typified capitalism was not that “some people had capital, but that most people only have wages.”

To be a proletarian is, in the absence of a culture of paternalism, to be susceptible to socialist propaganda. I work in a warehouse. I put hooks, and knobs, and handles in boxes and send them to Sheila White in Swindon, Matteo Schmid in Zurich, and Tony Rogers in Tunbridge Wells. Now, I’m lucky. Not only do I pack those products; I pick them. The warehouse I work in is small and the division of labour is, therefore, less extreme than it otherwise would be. Still, it does not stop me from waging a Marxisant class war in my head from 9 'til 5 each day, imagining an alternative use for the sticky tape with which I carefully seal my parcels.

However, what Chesterton understood better than anyone was that Marx was a false prophet. Instead of presiding over a fair distribution of wealth, communism would merely put capital in “the hands of even fewer people,” namely, politicians. Moreover, the difference between capitalism and communism as modes of production was modest. They were both centralised, impersonal, and monotonous civilisations, where ones’ life was set in a groove established by other people, people unknown to the individual beset by the officials’ or entrepreneurs’ baleful and philistine decisions. The only option was this: restore property to the masses once more, not in the form of collective ownership, but in individual parcels of land.

Chesterton distinguished, then, between private enterprise and private property. They were certainly not incompatible, but under capitalism, the extension of business was almost invariably at the expense of personal belongings. With a logic of gross inevitability, the one tended to consume the other. Yet it is precisely private property that confers dignity and meaning to a life, he posited. A propertied person is a free person. A person who reproduces themselves directly, day in day out, unaided by outside help and complex machinery, is a fulfilled person. Unlike the one-dimensional men and women of industrial society ensnared by the division of labour and the proliferation of bullshit jobs, a peasant leads not merely a simple life, but a complete one.

For a peasant, on Chesterton’s reading, property is a point of honour. Peasant society is not acquisitive. It is only capitalism that creates inequality through the process of buying and selling. Independence, Chesterton averred, is “valued exactly as any other dignity is valued when it is regarded as normal” by a society. That is to say, it is not to be merrily traded away. And, historically speaking, according to Chesterton, it hasn’t been. For capitalism to develop organically has been the exception, not the rule. It is “a monster which grows in deserts”, it emerges in spaces only where the older civilisation is sparse or indeed entirely absent: the North of England rather than the South and North America rather than Europe.

Tenuous history? Perhaps. Or rather, most definitely. Without doubt, Chesterton worked with a very broad brush in painting his picture of the past. Nonetheless, he was right to pour scorn on the fatuous claim, endlessly recycled by the partisans of “progress,” that “peasants are dreary and degraded savages, crawling about on all fours and eating grass like the beasts of the field.” To Chesterton the superiority of the peasant over the proletarian or bourgeois was plain. Peasants held stately and ceremonial dances; they produced beautiful embroideries and handicrafts; and, crucially, they knew the causes of things. In contrast to the modern urbanite and townsperson, the peasant knew that milk does not originally come from cartons. In many ways, as any good anthropologist will tell you, these pre-industrial subjects were far more intelligent than you and I.

Chesterton may have engaged in some romance (although it must be said, this can be easily overstated). His predilection, however, for the independent proprietor is readily explicable. When I was a child, most of the men I knew were self-employed tradesmen. They were affable, upright, plain-speaking individuals, who owned their own tools, managed their own time and knew their own worth. Self-assured and self-respecting, they were not crushed by life, depressed and disgruntled, like my colleagues and those like them condemned to perform a single, senseless task. They were not asked to demean themselves in robotic, superfluous activity. They did things that needed to be done. And consequently, as true equals, they harboured no resentment towards their clients or the world at large. Happy, indeed, “were he who could know the causes of things.” I know as much from experience. Distributism, moreover, is also more practical than it sounds.

As a proponent of Original Sin, Chesterton was a realist. With distributism, he did not offer perfection. What he offered, instead, was proportion, a mixed economy comprising private and public property, rural life and aspects of urbanity. Distributism could merely mean the gradual extension of profit-sharing. It could mean the management of every business by a guild, which organises themselves and distributes the proceeds of their industry in a more radically egalitarian way. Or it could mean, as Chesterton wanted it to, small economies of largely self-sufficient farmers, producing and consuming within their social circles. A Chestertonian peasant state did not mean that all people must be peasants in the way that, in a communist state, all people must be communists. All the same, for Chesterton, the only truly reasonable person was “the peasant who owns his own well,” since it is this kind of small proprietor alone who is properly independent.

Chesterton, to be sure, did not imagine that a majority were secretly hankering for “a simpler sort of England.” However, the number of people who did want “to get back nearer to the root of things, where things are made directly out of nature,” was not inconsiderable, he surmised. He guessed this from the attention suburbans lavished upon their gardens; from the way the rich were envied for the empty spaces they enjoyed; because of the general desire for the country he observed among the populace; due to the popularity of breeding or training animals; and owing to the reluctance of slum dwellers to give up a rabbit in a rabbit-hutch or a chicken in a hen-coop. The same could be said today of phenomena such as “wild swimming,” urban bee-keeping, or “wild camping.” For a significant portion of the population, the attraction of a simple, strenuous life is strong. Even so, it did not matter much to Chesterton if enthusiasm for peasant life was lacking. If apathy prevailed, ardour would simply have to be generated instead. The alternative was social failure.

“The sort of call that must be made on the modern English,” he wrote, “is the sort of call that is made before a great war or a great revolution.” Commerce was bankrupt. Trade was not coming back. The formation of a neo-peasantry represented the only viable way out of the impasse. With parliament beset by hypocrisy and inertia, what was needed was volunteers. Chesterton identified two sorts of recruit: first, actual or potential peasants, who were ready to “take over the responsibility of small farms, for the sake of self-sufficiency, of real property, and of saving England in a desperate hour;” and second, landlords who were prepared to furnish the land for such an experiment. In 1914, it was possible to raise “three million heroes with a blast of a bugle.” If the trumpet was sounded again, a new crisis as menacing as a great war could also be met. If England was to eat, he averred, its citizens would have to take “independent individual action on a mass scale.”

To modern ears, Chesterton’s strictures sound like hyperbole. British society did not self-destruct in 1926. Global capitalism did not implode, irrecoverably, in 1929. It came close in 1939-45. But for the thirty years, between 1945 and 1979, it fared remarkably well. It was precisely during that period, however, a time of prosperity and consumerism for all, that we prepared ourselves for real catastrophe. Through our addiction to comfort, hygiene, and luxury, we created a natural environment hostile to human life, and due to get much more belligerent. Chesterton, in other words, was ninety years too early. Had he succeeded in mustering his army of volunteers we would have averted disaster. But his call for a military-style conscription of peasants sounds incredibly current, uncannily so.

Chesterton was apposite then. He is essential now. It is a question of survival. Yet, even if it wasn’t, we still ought to listen carefully to what he had to say: ‘There is no obligation on us to be richer, or busier, or more efficient, or more productive, or more progressive, or in any way worldlier or wealthier, if it does not make us happier.” Postliberals should not forget him.

right on in my opinion. if we don't heed this, and fairly quickly, we will not survive, tenuous as survival is anyway under collapse.