US Engages a Chastened Modi in Office

India Cannot and Will Not Be a Hindu Rashtra

The US president Joe Biden has deputed his trouble shooter National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan to travel to New Delhi no sooner than Prime Minister Narendra Modi forms his new government. This may remind us in some ways of the 1990 Mission by Robert Gates, then deputy national security advisor in the George HW Bush presidency to New Delhi in the shadow of a purported impending nuclear apocalypse in the subcontinent.

Of course, history never repeats itself. The “Gates Mission,” as it is known in diplomatic archives, had at its core a tricky nuclear non-proliferation agenda that Washington was navigating thirty-five years ago at a juncture when New Delhi could not depend anymore on Moscow as a pivotal ally.

However, today, there is a profound difference. A resurgent Russia under Vladimir Putin’s leadership has recaptured the verve of the “privileged strategic partnership” with India. The Ukraine conflict turned out to have a “multiplier effect” on that relationship.

The Indian ambassador to Moscow Vinay Kumar told Izvestia two days ago that India has not yet decided on participation in the forthcoming conference on Ukraine scheduled to take place in Switzerland next week, which cannot be a fruitful event without Russia’s participation; and, furthermore, that India will support the proposed peace plan for Ukraine only if it is approved by both sides of the conflict. This must indeed be music to Russian ears.

So, what is Sullivan’s mission to Delhi about? The White House said in a readout that Sullivan plans “to engage the new [Indian] government on shared U.S.-India priorities, including the trusted, strategic technology partnership.”

Nikkei Asia reported quoting Mira Rapp-Hooper, Special Assistant to the President and Senior Director for East Asia and Oceania at the White House National Security Council, that Biden plans to attend the summit of the QUAD in New Delhi after the US presidential election in November.

“The preparatory work for … the [QUAD] leaders’ summit is well underway… And we are very confident that we will have really substantial deliverables that continue to build upon the QUAD’s mission,” she revealed.

That said, it is predictable that Sullivan will keenly explore the positioning of New Delhi in the tumultuous developments lately in the confrontation between the US and Russia. Things have come to such a dangerous pass that Biden felt it necessary to rule out a US missile attack on Moscow and the Kremlin!

Putin, in turn, reminded the US that Russia can also pay back in the same coin by allowing its weapons to be sent to regions where there are actors locked in mortal combat with these very same western powers that supply weapons to Ukraine to attack Russian territory.

Conceivably, Sullivan will make another determined attempt to force the weakened Modi government to join the Western camp as a natural ally. Whereas, India has become a mainstay of the Russian economy due to its massive purchase of Russian oil.

India’s Bank of Baroda reported that the country’s imports of Russian oil soared tenfold in 2023. Russia has successfully weathered the EU embargo on Russian seaborne oil and the West’s price cap by rerouting most of its energy exports to Asia – particularly to India and China. According to the Russian Finance Ministry, income from energy exports between January and April soared by 50% compared to the same period in 2023.

Reuters reported that last month, India’s largest private corporation Reliance Industries and the Russian company Rosneft signed a one-year contract for monthly supplies of up to three million barrels of oil that will be paid for in rubles. This is the unkindest cut of all, since cross-border settlements in local currency undercuts the West’s attempts to cut off Russia’s access to its financial system while promoting “de-dollarisation.”

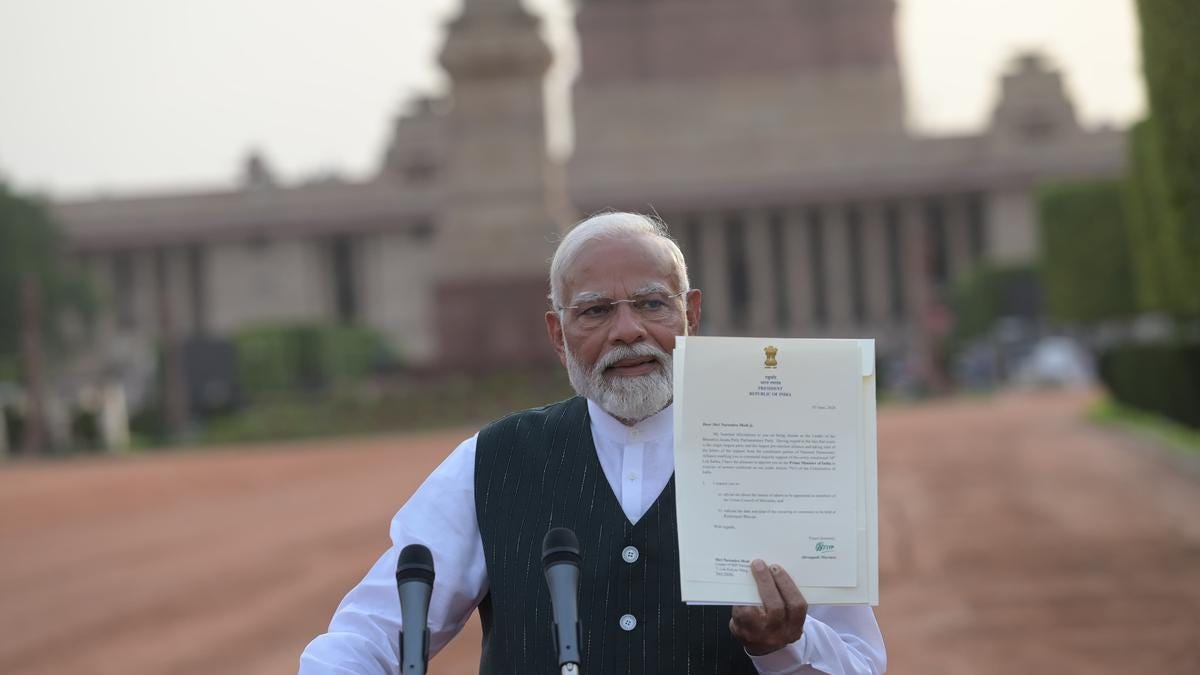

Suffice to say, India has successfully pushed back the US pressure. But the recent parliamentary election has been a big setback for the ruling BJP (Bharatiya Janata Party) and Modi personally. There is palpable angst in the Russian commentaries on Modi’s pyrrhic victory.

On the contrary, across the board, there is a sense of elation in the western commentaries, which estimate that the election has diminished Modi’s “stature as an elected strongman with a mission from God.” An expert opinion at the influential Council for Foreign Relations noted that Modi will be leading a “fragile coalition” and will be facing daunting economic and social issues that have no easy solution.

The Cfr commentary concluded that “Another challenge relates to India’s foreign relations. Modi and the BJP have massively traded on his reputation of popularity and his credentials as a devout Hindu nationalist with a new vision for India. Both of these have now received a setback… there is little doubt that Modi’s stature of invincibility as a leader of a rising power and a community of Global South nations with a large mandate has been diminished abroad.”

To be sure, Sullivan will look for opportunities to navigate US interests from a position of strength—something Modi resisted. The US traditionally abhors “strongman” politics, especially in the Global South.

From such a perspective, Sullivan can be trusted to explore the advantages that may now be opening up. Without doubt, India’s Russia ties will be listed somewhere at the top of his talking points. But there are other pressure points too, which the Biden administration had developed during the past several months, especially the Modi government’s alleged assassination plots in North America.

However, at the end of the day, the election result may hold the potential to do good for the US-Indian relationship, if handled with sensitivity. The election is living proof that India remains a vibrant democracy and, therefore, has much in common with the liberal democratic world that the western media is unwilling to acknowledge. With some effort, India can even aspire to be a model democracy.

As an opinion piece in the Hill newspaper put it, “The result of India’s latest elections is in some ways a reminder of how democracies can successfully apply self-correction mechanisms. In addition to concerns about over implementing BJP’s Hindutva ideology, which equates Indianness with Hinduism, some observers were worried about the prospect of authoritarianism in India.”

Clearly, the anxiety that democracy was dying in Modi’s India was vastly exaggerated.

Secondly, in a curious way, the human rights situation in India is likely to improve under a coalition government that takes recourse to consensual politics and where there is a strong opposition in the parliament. Indeed, Rahul Gandhi is now a serious contender for power.

All this restores the political balance, with the Congress in a position to insistently question the government’s policies and the ruling BJP obliged to be accountable.

Equally, the reassertion of regional parties highlights India’s ethnic diversity. Thus, the rhetoric of “cultural nationalism” though the past decade, which pitched India’s Hindu majority against the country’s Muslim minority and helped the BJP in the previous two general elections, has run out of steam.

People’s primary concerns are about economic distress, and the limits of religious identity as a basis for voters’ choices have been reached. The bottom line is that India cannot and will not be a Hindu Rashtra.

Suffice to say, a major concern of the western world—that India was lurching toward ethno-nationalism and falling victim to its attendant dangers of militancy and extremism—stands defused. This helps the US-Indian discourses.