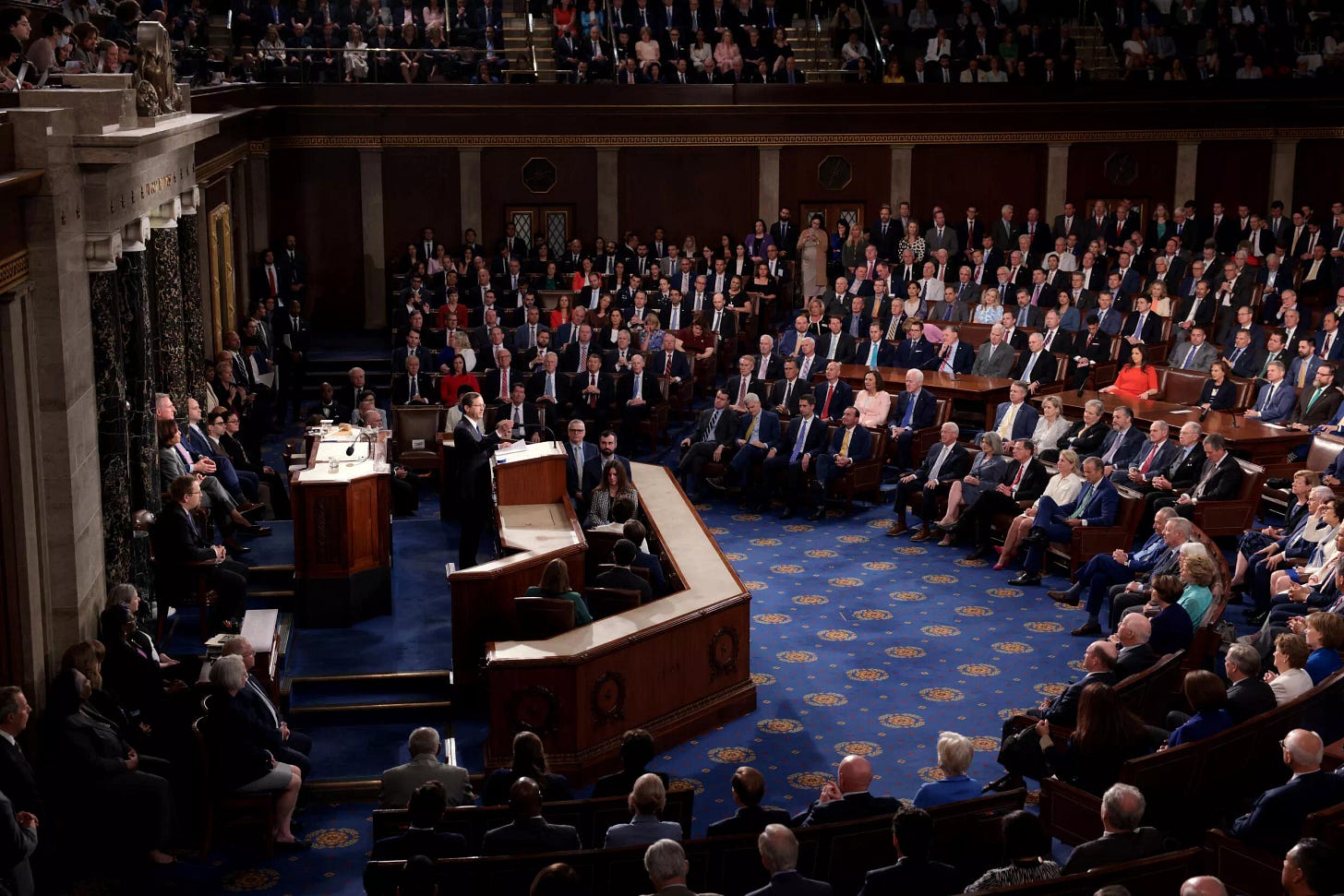

Israeli President Isaac Herzog added nothing of great value in his speech at the United States Congress on 19 July.

His was the typical language. He spoke of a “sacred bond,” touted the shared experience between both nations as “unique in scope and quality,” and celebrated the great, common “values that reach across generations.”

But this theatrical language was meant to hide an uncomfortable truth: the relationship between Israel and the US is changing at a fundamental level.

Two days before Herzog’s speech, Israel’s opposition leader and former prime minister, Yair Lapid, declared that “the United States is no longer (Israel’s) closest ally.”

Lapid’s words were a mix of facts and political opportunism.

Lapid and others in his camp are keen on blaming Israeli Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, for the waning relationship between both countries; or to use more pertinent language, for weakening the “sacred,” “unbreakable bond,” which has for many years joined the two countries together.

Lapid’s assessment, however, is imprecise. While it is true that Netanyahu played a role in widening the distance between Tel Aviv and Washington, that distance was growing based on other dynamics—a mixture of political, geopolitical, and demographic changes and trends.

But whose assessment is closer to the truth? Herzog’s claim of a “sacred bond” or Lapid’s more dramatic assertion of a faltering alliance?

To address this question, we must look beyond the exaggerated public statements made by officials from both countries and particularly from the leaders of the US’ two powerful parties, the Republicans and the Democrats.

In terms of language, the leaderships of both parties insist that Washington’s devotion to Israel is beyond politics and that Israel’s security is above America’s own political polarization.

In a speech at the Israeli Knesset (parliament) on 1 May, US House speaker Kevin McCarthy followed the typical American script on Israel. He, too, spoke of “unbreakable bond” and “bipartisan US support” and, expectedly, was met with resounding applause.

Biden, too, is a resolute supporter of Israel. His oft-repeated phrase “You don’t have to be Jewish to be a Zionist” is now a mantra among US allies of Israel.

Yet, while Republican kinship to Israel remains strong, that of the Democrats is not; so weak, in fact, that in June 2022, a Pew Research Center poll said that “more Democrats and those who lean Democratic express a favorable view of Palestinians than of Israelis.”

So, the notion that Israel is a common cause between America’s top political parties is simply untrue. No wonder that Biden has, for seven months, delayed inviting Netanyahu to the White House following the formation of Israel’s latest government coalition.

Crowded with far-right politicians, Netanyahu’s coalition is simply a liability to any democratic system anywhere in the world.

Many Israelis agree, believing wholly or partially that their government is no longer democratic—due to Netanyahu’s growing control over the country’s once-independent institutions.

Amid all of this, Biden is struggling to find the balance.

“I'm very concerned,” Biden told reporters last May. “(Israel) cannot continue down this road, and I've sort of made that clear."

This is the same Biden who described as “bizarre” a proposal by former US Presidential candidate, Bernie Sanders, to withhold funds from Israel due to its mistreatment of Palestinians.

Washington gives Israel at least $3.8 billion annually in military aid. If the anti-Israel trend among Democrats continues, the calls of withholding funds might, in the coming year, no longer appear so “bizarre.”

Under intense pressure from the pro-Israel lobby, on 17 July, Biden finally invited Netanyahu to the White House. The visit, however, considering the intensifying anti-Netanyahu protests, is unlikely to reset the relationship between Washington and Tel Aviv.

In fact, even if the protests subside, relations between the US and Israel will not be the same.

For over a decade, the US has slowly, but unmistakably, walked away from the Middle East, partly because of the disastrous outcomes of the Iraq invasion, and partly due to the growing power of China in the Asia-Pacific region.

The US retreat has rung alarm bells in Israel, with Israeli politicians and mainstream intellectuals urging self-reliance. This led to an unrelenting Israeli search for new allies, mostly in the Global South.

The success, from Netanyahu’s viewpoint, of this campaign has helped Israel somewhat liberate itself from any commitment to the US agenda in the Middle East, including engaging in the US-led “peace process” with the Palestinian leadership.

Despite Biden’s insistence, during his Middle East trip in July 2022, on the need for a “reinvigorated” peace process, Tel Aviv neither supported nor even seemed to notice Washington’s new quest.

Back then, Netanyahu was not even a prime minister, as Israel was ruled by a government coalition under the leadership of Lapid himself.

While Netanyahu is being conveniently blamed for the dwindling ties, the disengagement from Washington was, in fact, mostly a collective decision and protracted process.

When, on 10 July, Israel’s far-right minister of National Security, Itamar Ben-Gvir, declared that “President Biden must internalize that Israel is no longer another star in the American flag,” he was merely reiterating a popular line used by others before him.

Even Netanyahu resorted to similar language when, in March, he told the US Administration that Israel is “a strong, proud and independent democracy.”

Though much of Israel’s self-proclaimed “independence” was an outcome of unconditional US support, Israelis hardly acknowledge this fact.

Israel’s Ministry of International Defense Cooperation Directorate (SIBAT) is constantly reporting on the growth in Tel Aviv’s military exports to the rest of the world. These exports reached $12.5 billion last year. Most of this technology was either developed by the US, or jointly with the US, and much of the research was funded by American taxpayers.

Nonetheless, this sense of “independence” has given Netanyahu the needed confidence to abandon the Democratic Party in favor of the more accommodating Republicans.

For their part, the new generation of Democratic politicians is viewing Israel, at least the Israeli Right, as an extension of the Republican Party, thus the growing hostility towards Israel.

In the final analysis, both Herzog and Lapid are partly wrong: The “sacred bond” is less sacred than ever and, whether the US is Israel’s closest ally or not, it makes little difference, since Israel is unlikely to find an alternative to Washington’s blind support anytime soon.