Understanding Libya’s Relentless Destabilisation

A Brief History of Libya’s Ethnic, Cultural and Islamist Disputes

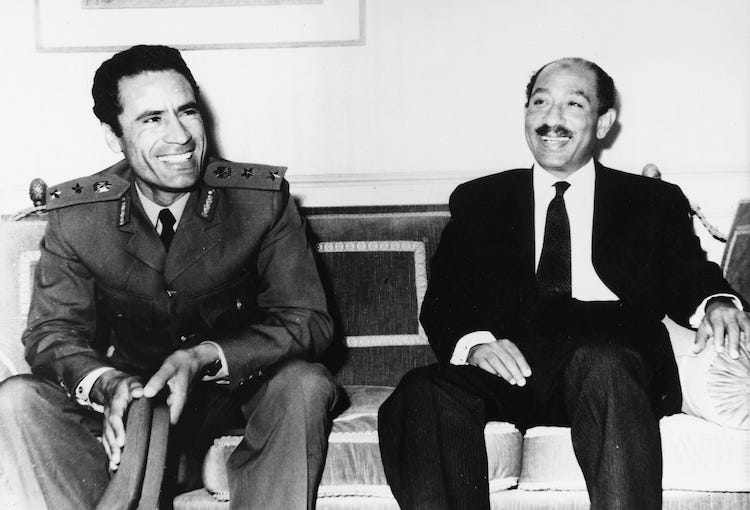

After leading a military coup in 1969, Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi cemented his rule over Libya for more than 40 years. A variety of different political ideologies—Pan-Arabism, Pan-Africanism, socialism, Islamic leftism, and others—characterised his leadership, which were further reinforced by a cult of personality. While living standards for Libyans increased under his rule, Gaddafi attracted resentment among some non-Arab populations, Islamic extremists, and other political opponents.

As the Arab Spring spread outward from neighbouring Tunisia into Libya in February 2011, protestors and militant groups seized parts of the country. Loyalist armed forces retook control of much of what they had lost over the next few weeks after the outbreak of the protests, but Gaddafi’s historical antagonism toward Western governments saw them seize the opportunity to impose a no-fly zone and bombing campaign against Libyan forces in March 2011.

Alongside assistance from regional Middle Eastern allies, the NATO-led intervention was successful in helping local militant groups topple Gaddafi, who was later captured and executed in October 2011. Soon after his death, questions were immediately raised about how Libya could be politically restructured and avoid becoming a failed state. After militant groups refused to disarm, they along with their allies began to contest territory and control over Libya’s fragile new national institutions.

The National Transitional Council (NTC) was established to coordinate rebel groups against Gaddafi, and naturally inherited much of the Libyan government after the war. But a number of countries did not recognise its authority, and after handing power over to the General National Congress (GNC) in 2012, Libya’s weak central government steadily lost political control over its enormous territory to competing groups.

Libya’s population of almost 7 million people lives in a highly urbanised society that has led to the development of strong regional identities among those living in its northern coastal cities. There has also historically been an east-west divide between the two coastal provinces of Cyrenaica in the east and Tripolitania in the west.

A large Turkish and part-Turkish minority also live throughout Libya’s major cities, particularly in the city of Misrata. Most of them have descended from the Ottoman troops who married local women during Ottoman rule from 1551-1912, and though not a strictly homogenous group, the majority revolted against Gaddafi as nationwide protests began in Libya.

The historical lack of central authority in Libya’s more rural south resulted in widespread autonomy for the Tuareg tribe in the southwest and the Tubu tribe in the southeast. While the Tuaregs largely supported Gaddafi, the Tubu joined the revolutionaries, sparking increased tension between these two tribes to gain control over the city of Ubari, local smuggling routes, and energy infrastructure.

Alongside ethnic and cultural disputes, Libya was further destabilised by radical Islamists after the fall of Gaddafi. Mass unemployment among Libya’s relatively young population fueled recruitment for ISIS and the Al Qaeda-affiliated Ansar al-Sharia. Having gained battlefield experience and with limited economic prospects, many militants in Libya had little incentive to return to civilian life, while the influx of foreign jihadists also kept the violence ongoing.

Rivalries between these numerous factions helped lead to the outbreak of the second Libyan civil war in 2014. The UN-brokered Libyan Political Agreement (LPA) was signed in December 2015 to create a Presidential Council (PC) for appointing a unity government in Tripoli but failed to curtail growing violence between local actors.

Two major entities came to dominate the country. The Government of National Accord (GNA), which was presided over by the PC, was recognised in March 2016 to lead Libya, with Fayez Serraj as the Libyan prime minister. This move partly incorporated elements of Libya’s political Islamic factions.

The Libyan House of Representatives (HoR), meanwhile, refused to endorse the GNA and relocated to Tobruk in Cyrenaica after political pressure and Islamist militias forced it out of Tripoli in 2014. The HoR is led by former General Khalifa Haftar, who commands the Libyan National Army (LNA).

The GNA retained official recognition by the UN as well as Libya’s most important economic institutions, including the Central Bank of Libya (CBL). But both the GNA and the HoR continued to fight for influence over the National Oil Corporation (NOC), while many other national institutions were forced to work with both factions.

Military force has also been integral to enforcing rival claims to Libya’s leadership. In 2017, Haftar’s forces seized Benghazi, consolidating power across much of the east and centre of the country. But his attempt to take Tripoli in 2019-2020 was repelled by GNA and allied forces, prompting an HoR retreat on several fronts. A ceasefire between the GNA and the rival administration of the LNA declared an end to the war in October 2020, but tensions and violence persisted.

Libya’s civil conflict has also been inflamed by outside powers. Turkey opposed the original NATO-led intervention in 2011 but supported Libyan Turks, some of whom founded the Libya Koroglu Association in 2015, to coordinate with Turkey. Ankara has also supported the GNA with arms, money, and diplomatic support for years, and Turkish forces and military technology were integral to repelling Haftar’s assault on Tripoli.

Turkey’s business interests in Libya and desire to increase its power in the Mediterranean remain Ankara’s core initiatives, and in June it voted to extend the mandate for military deployment in Libya for another 18 months. Both Turkey and Qatar, which has also been a strong backer of the GNA, are close with the Libyan branch of the Muslim Brotherhood and associated political circles in Libya, to attempt to promote a brand of political Islam that rivals Saudi-led initiatives.

With few core interests in Libya, the U.S. has shown tacit support for intervening again in a conflict it had allegedly won, but from 2015 to 2019, U.S. airstrikes and military support helped the GNA push ISIS out of many Libyan cities. Yet, Washington has remained wary of being associated with the Libyan conflict and with Islamists allied with the GNA, and the U.S. harboured and provided support to Haftarfor decades to pressure Gaddafi before the civil war.

Egypt has been one of the HoR’s most crucial allies, providing weapons, military support, and safe haven through Libya’s eastern border. Besides protecting Libya’s Egyptian population, Egypt’s military-led government is also seeking to suppress political Islam in the region after Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood briefly ruled Egypt from 2011 to 2013 following Egypt’s own revolution. In 2020, Cairo approved its own intervention in Libya.

Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) have similar interests in suppressing rival political Islamic forces in the region and have provided funding and weaponry to Haftar. Doing so has brought them closer to Russia, which has also supported Haftar with substantial military assistance. This includes warplanes piloted by the Russian private military company Wagner, which is suspected to be partially bankrolled in Libya by the UAE.

Libya’s destabilization complements the Kremlin’s attempts to influence Europe. Haftar’s forces and supporters managed to block Libyan oil exports in 2020 and again earlier this year, threatening continental supply and increasing Russia’s leverage. Additionally, instability in the region and porous borders encourage migrant flows to Europe, often increasing the popularity of right-wing political parties which have grown closer to Russia over the last two decades.

The HoR has also found less direct aid from France. Officially, Paris has supported UN negotiations and the GNA and has sought to minimise perceptions of its involvement in the conflict. But the death of three undercover French soldiers in Libya in 2016 showed that Paris remained deeply involved in the country’s civil war, and it has sold billions in weapons to Saudi Arabia and the UAE to help Haftar. This is part of France’s efforts to suppress Islamist groups in Africa, where France retains considerable interests.

France’s position has brought criticism from Western allies. In 2019, Paris blocked an EU statement calling on Haftar to stop his offensive on Tripoli, while its support for Haftar has severely undermined its relationship with Italy, which has seen its economic influence in Libya decline.

Since the conclusion of the second Libyan civil war in 2020, steps have been taken to unify the country. A Government of National Unity was established in 2021 to consolidate Libya’s political forces, and the new Prime Minister Abdul Hamid Dbeibeh reached an agreement with Haftar in July 2022 to enforce a ceasefire.

But based on the current dynamics of limited intervention, there is relatively little risk and high rewards for foreign powers to continue destabilizing Libya. Turkey and Russia are also using the conflict to add to their leverage over one another in Syria. With repeated delays in holding elections in Libya and rival local and foreign actors seeking to dominate the country, Libyan citizens risk continuing to be used instead of being helped to ensure a stable and secure future for their country.