Last winter, Hamline University made national news when it fired Erica Lopez Prater, an art history professor who had offended one of her students by showing a painting depicting the Prophet Muhammad. By all accounts Lopez Prater was a conscientious instructor who had provided her class with multiple warnings and opt-out opportunities before showing the image. Lopez Prater, it has been frequently noted, was also an adjunct instructor, the most exploited and vulnerable professor in the university hierarchy. While the administration, which described Lopez Prater’s act as “undeniably Islamophobic,” expressed its commitment to keeping students “safe” and “supported,” some observed that—considering the school’s exorbitant tuition and the fact that most of its students would likely graduate with overwhelming debt—its concerns about student welfare were facile and self-serving. Instead, it appeared that the administration was merely invoking politically correct ideology and pandering to students in order to do what employers do whenever they get the opportunity: control labor.

Conservatives generally responded to Lopez Prater’s firing with outrage (notwithstanding conservative “then-she-should-get-another-job” anti-workerism), insisting that the case was emblematic of woke, or politically correct, ideology “run amok.” Liberals and leftists also largely condemned the firing, although some argued that the university’s mistreatment of Lopez Prater occurred not due to woke ideology but in spite of it, with Hamline in fact betraying “true” liberal ideals of free speech and academic freedom. This argument, however, ignores key differences between woke ideology and liberalism, including their views on free inquiry and expression. Those advancing the “not a true liberalism” argument also, necessarily, assumed the authority to unilaterally deny the presence of a particular form of politics even as Hamline’s administration overtly identified with it. This “power to name” characterizes the story in another way. Namely, what does institutionalization imply for ostensibly liberatory politics? What would it say, for instance, if an African American employee were punished by white employers for racism? And insofar as administrators have weaponized wokeness to moralistically discipline labor, does this imply an appropriation of a previously radical ideology or indicate that the ideology has always been retrogressive?

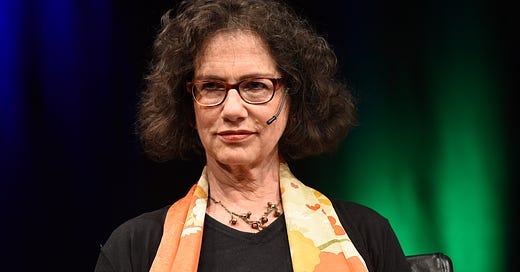

It is in light of these and related concerns that several left authors have recently published books seeking to clarify the meaning of wokeness and to distinguish it from liberalism and leftism. One such effort is Susan Neiman’s Left Is Not Woke, which asserts that woke ideology represents a repudiation of the left liberatory project that began with the Enlightenment, and that adherents of woke ideology have abandoned traditional left ideals of universalism, justice, and progress. Neiman asserts that today’s woke activists, though often well-meaning, have been unwittingly colonized by the misanthropic conservativism of philosophers including Carl Schmitt and Michel Foucault, who respectively teach, for Neiman, that we should embrace the friend-enemy divide and abandon all hope of changing our institutions since reform only produces more insidious techniques of oppression. Woke thinkers have similarly been hijacked by Adorno and Horkheimer’s Dialectic of Enlightenment, which advances a negative and surprisingly undialectical description of the Enlightenment; for Neiman, instrumental reason is neither negative nor dialectical but good. Mistakenly concluding that governments’ abuse of Enlightenment ideals means that the Enlightenment itself was “Eurocentric” and “colonialist,” woke activists, Neiman argues, have abandoned a project they know tragically little about and have instead opted for tribalism, an inability to distinguish justice from power, and a self-defeating nihilistic sense of doom instead of a liberatory belief in progress and hope. While acknowledging that woke politics originated as a corrective to the historic failures of leftism to grapple with racial and sexual oppression both inside and outside the left, Neiman asserts that woke ideology has deviated from its original path and has now become a regressive force.

To be sure, there is much to criticize about liberal identitarianism or wokeness. As others have noted, liberal identitarian politics notably expanded following the failures of more class-oriented protest movements within the context of a contracting welfare state. Competing for increasingly scarce resources, identity politics has also followed the structural pathways engineered by the most undemocratic of all government institutions, the Supreme Court, which allocates rights to groups based on race, ethnicity, religion, disability, and sex, but not poverty or class. Glorifying victimhood upon the premise that, as Neiman paraphrases it, “the voice of pain is the most authentic,” woke ideology can be said to advance the interests of elites from historically marginalized groups at the expense of members of other, historically advantaged, groups. In so doing, wokeness opportunistically commandeers, rather than structurally challenges, exploitative institutions. Because wokeness presents self-appointed spokespersons as stand-ins for whole groups, it additionally prefigures a backlash that harms vulnerable people on the ground rather than the insulated elites who self-servingly speak in their name.

While one could identify relatively innocuous precursors to the Democrats’ identity politics in the ethnic-based resource allocation of Tammany Hall, one could also identify parallels by examining contemporary cases of genocide. Discussing the civil wars that have repeatedly plagued postcolonial states, Mahmood Mamdani’s Neither Settler nor Native forcefully criticizes the “politicization of cultural identity.” Beyond the politics of redistribution and social equality, this politicization is ultimately based on the question of who is included in, and excluded from, the political community. Mamdani shows that fluid and heterogeneous identities preceding colonialism were distorted and ossified under colonial government, which buttressed its rule by allocating resources to privileged minorities that it defined into being in order to grant legibility and legitimacy to the colonial system at the primary expense of an embittered majority. The consequences following independence have often been catastrophic and, at times, genocidal. In the U.S., this “politicization of cultural identity” has accompanied both political parties’ increasing adoption of the language of illegitimacy (in which Obama was not a U.S. citizen, Trump was a Russian mole, and Biden stole the election) along with a retaliatory political vindictiveness featuring threats of imprisonment of rivals and escalating administrative turf wars. This does not guarantee civil war or genocide, but it is no less a bad sign for those who fear an increase in political violence.

At the same time, positing that the answer to woke tribalism and its growing backlash is to return to Enlightenment values is not especially persuasive, as it overlooks trenchant good faith critiques of that movement as well as the historic question of how we arrived at woke thinking in the first place. Commenting on MoMA’s 1955 “Family of Man” exhibit that depicted the supposed universality of birth, marriage, and death, Roland Barthes reportedly commented, “Tell that to Emmett Till.” It has been quite obvious for a long time that different groups experience social existence, depending among other things on their race and sex, in different ways. Neiman does not dispute this, but asserts that universality should be taken as a normative claim that, although unfulfilled, provides us with a constructive political orientation. It is undoubtedly true that the ideal of Enlightenment universality spread like wildfire beyond the imagination or even intent of its originators, bringing to mind accounts of the Haitian revolutionaries singing the Marseillaise before battling their dumbstruck French colonizers. The trouble, though, is how, without falling into the fallacy of “not a true Scotsman,” do we praise Enlightenment liberty for the Haitian Revolution without blaming Enlightenment instrumental reason for everything from Nazi genocide to climate change?

There are nonetheless other ways, beyond the language of hypocrisy and unfulfilled ideals, of thinking about universalism. On one hand, Jefferson’s assertion that “all men are created equal” (i.e., kings and white male elites) was undoubtedly revolutionary and would have constituted blasphemy in the Middle Ages. On the other hand, it is ahistorical to suggest that such universalism, excluding the majority of humanity and written by an owner of slaves, was inauthentic or incomplete and merely needed time for the requisite “progress” to fulfill its true purpose. Rather, the Declaration of Independence complained that King George III was not only taxing the colonists but also preventing them from settling west and thereby destroying the indigenous population. That is, the Declaration’s universalism was based not on an abuse of freedom but on a freedom defined in part by the right to be unconstrained from oppressing those excluded from or subordinated within the political community. At minimum, as Adorno and Horkheimer carefully explain, there is a dialectic at work, which is why the universalism of the French Revolution produced, in practice, a legally standardized French citizen equivalent to all other French citizens, legible to the state for purposes of governance, taxation, and war-making. To speak of rights, then, as abstract claims apart from their historic authorization (and recurrent withdrawals via Schmitt’s states of “exception”) is to abandon materialism for metaphysics, a move that is highly germane to the left-woke debate but unexplored by Neiman.

While Neiman has little patience for Adorno and Horkheimer or Foucault, she is generous with those philosophers she agrees with, arguing that woke thinkers should jettison their “bad theory” by acquainting themselves with Kant, Voltaire, Rousseau, and Diderot. Neiman scoffs at woke thinkers who believe that the Enlightenment was Eurocentric, and instead compares Diderot’s fulminations against European colonialism to the postcolonial writings of Frantz Fanon. Here, though, is one of several cases of Neiman talking past her opponent, failing to interrogate what a good faith critique of Diderot might look like and what it would imply about woke ideology. Diderot was appalled by Europe’s brutalization of indigenous populations, whom he treated as theoretical equals. Simultaneously, in Principles of Colonization, Diderot wrote:

Both reason and equity permit the establishment of colonies, but they also mark out the principles from which one must not stray when founding them… If it is fully inhabited I can lay legitimate claim only to the hospitality and assistance which one man owes another… If the country is partly deserted and partly occupied, then the deserted part is mine…. I can extend my domain up to the borders of his land… An uninhabited and deserted country is the only one which can be appropriated.

It is not simply that Diderot is projecting a European conception of private property and borders onto other, pre-enclosed, peoples, whom he anticipates will ultimately “realize that the arts and knowledge which had been brought to (them) were very favourable to improve (their) condition” (if Diderot is not being Eurocentric here, the term has little meaning). Nor is it merely that he is in effect providing guidance to states for improving, and thereby ultimately legitimizing, conquest. It is that he is justifying all this while assuming the authority to speak for the interests of others, marginalized peoples whom he does not fully understand. Even given the best of intentions, this dearth of humility, perhaps best exemplified in Graham Greene’s Quiet American, has been disastrous for the world.

Neiman proceeds to make the case for historic progress by asserting—ironically considering her criticism of standpoint epistemology—that a hypothetical African American man who had lived through the Jim Crow era would reject the claim that progress does not exist. While it goes without saying that Neiman’s hypothetical man would claim whatever his inventor wanted him to, on what basis should we, even if he were real, listen to him? Neiman, following Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò’s critique of standpoint epistemology in Elite Capture, questions whether suffering alone provides insight, while conceding that we ought to listen to people who have direct experience with matters that concern us. But what would it imply if Neiman’s hypothetical victim of Jim Crow met a younger African American man, who had been incarcerated in the 1990s for drug possession and who insisted that the War on Drugs and the era of mass incarceration were actually worse than Jim Crow? Those invoking the voice of the marginalized, a move regularly made by the woke, would be forced to explicitly do what they were already doing in the first place, make judgements about which marginalized voices to listen to and amplify and which to ignore, assuming the authority to decide who deserves to be heard.

In a similar vein, Neiman asserts that a victim of pre-Enlightenment torture would surely prefer contemporary prison to being burned alive or drawn and quartered in a medieval dungeon. Neiman condemns Foucault for not acknowledging what for her is unambiguous progress and for refusing to help the world progress further. A prison reformer, attempting to improve prison conditions and the lives of prisoners, would be exasperated, Neiman complains, by Foucault’s refusal to tell us what to do and his apparent collapse of all normative distinctions when discussing the evolution of institutional power. Neiman’s complaint here is quite familiar, echoing the complaint that liberals make when leftists, for example, refuse to vote for Democrats or otherwise support oppressive institutions whose only alleged virtue is being less oppressive than other oppressive institutions. As in those debates, Neiman does not adequately confront the fact that she and her interlocutors do not represent different points on a liberal-left spectrum, who want more or less the same thing, but instead have incommensurable values that inform, rather than merely reflect, different theoretical understandings. Putting aside that modern prisons’ use of solitary confinement is a harrowing form of torture that has been shown to cause brain damage, prisons’ fundamental purpose is domination. Adopting the values that would encourage us to “improve” such an institution can only mean that we have already lost.

Criticism of the Enlightenment of course does not mean that wokeness is designed or equipped to liberate us. On the contrary, woke ideology is fully enmeshed in institutional power, which it revitalizes with a moralizing force based in, as Foucault put it via Gilles Deleuze, the “indignity of speaking for others,” a practice that even its critics struggle to escape. Still, it was not long ago that conservatives, denouncing the violence and disorder of the French Revolution, called for a return to the Ancien Régime, where society was regulated by the traditions of centuries-old institutions. Their liberal detractors responded by asking how it was that a system that was so desirable and stable produced the conditions that led to its collapse.

1. Respectfully, always wary of those who teach political science/history. Usually means not a historian.

2. Only the 1% could understand any of this, so how does this speak to or for the oppressed masses of the West/world any more than Woke elites do?

3. Agree fully with the critique of that Woke assumption of speaking for the oppressed. They are doing a terrible job from their 3-bedroom suburban homes, earning capitalist paychecks while parroting Marx, Fanon, Freire and Said.

(This is why we can’t trust the far Left.)

4. Mamdani does not ‘show’ anything about colonial identities. He makes up whatever suits him, like Said, Foucault, Fanon did, and 95% of leftist scholars do. Hows that Uganda working out for you Mahmood? Or India for that matter? He is making it all up, due to his Afrocentrism and idealization of Uganda, Rwanda and well everywhere in Africa. Life is good at Harvard though!! Historians of all stripes on the other hand know very well how collaborative, cemented AND fluid, neither this nor that, and how packed with agency were all those ‘colonial identities’ – whatever that might actually mean for hundreds of millions of separate individuals over centuries across the whole planet. Which colonial government ossified all that glorious arcadian pre European identity fluidity? Colonial govts all differed, from year to year, state to state, governor to governor. Generalization is pointless, about ethics, or profits, let alone personal identities. How au courant.

5. These ever increasing claims about present day colonial consequences are never based on clear historical causation. They are assumed or at best correlative. How do you even calculate what caused this or that today, here in the US, in Ireland, Botswana, Chile or China. Its impossible.

6. Criticizing the Enlightenment is like criticizing capitalism, ‘politicians’ or ones parents. Its banal. Without the Enlightenment, there would be no freedom for the likes of those noted above (and todays Woke scholars) to express their partially Marxist, utterly partisan, selfserving, mostly made-up viewpoints. (Except Foucault of course, privileged party boy who could say what he wanted and do what he wanted…) To anybody who comfortably, loudly, fearlessly critiques the Enlightenment from their cushioned couches, their joyful 9 month jobs and their well-filled bellies, I say: tell me all about the other traditions around the world in 1800. In fact why don’t you go to those places now. Then call us, if you can, when you get there, and let us know how Woke scholars in the West can claim the Enlightenment was somehow responsible for all the authoritarian cultures worldwide that long preceded its emergence in Europe, that thrived alongside it, that repudiated it consistently against the best advice of well-intentioned Europeans, that gained from many of its precepts - all those authoritarian cultures that are now more than ever now thriving worldwide in oppression, abuses, corruption and censorship - except for in, well, the region the Enlightenment originated. (The US as ever is a mixed bag….but)

7. The Enlightenment WAS mostly responsible for the Haitian Revolution. That’s clear. And Wilberforce. And Quakers. And of course many brave enslaved people. But, oh have you read what happened when the rebels were left to themselves? Interesting history there, but never noted normally. Division, fraction, black on black difference, regional rivalries, fissures from those with slave to middling to free status, across ideology, across class status, and so on. Why do I mention this? Because that is how, if we must generalize, essentially every indigenous kingdom was prior to the arrival of the vile Enlightenment minded white devils. Just like Europeans. They were all the same. They were all weird early modern humans, from Paris to Manila, to Paraguay to Mali . The noble savage idealization is so 1950s, but it persists. “They were oh so happy before…!!!” Right. Give me some Azteca sacrifice partying over a Bud light anytime.

8. The Enlightenment was certainly NOT responsible for Nazism. That was the epitome of anti-Enlightenment, rightwing conservative nationalism gone to hell and its extremes.

(This is why we can’t trust the far Right.)

9. Why would Diderot NOT be Eurocentric? In 1780? Was Al Wahabi Islamocentric? Was the Qing Emperor Sinocentric? The king of Kongo Afrocentric? The Shogun Japanocentric? Why do we expect SO much more of 18th century Europeans? Its not as if they were racially or intellectually superior or anything ridiculous like that…His Encyclopedie is actually very Woke for the time. And pretty much any elite from the non-West then would have praised its incredible depth of knowledge, if they could read.

10. Wokeness is worse than conservatism for free speech. Hurts me to say that, but its obvious.

11. Neiman is right. Otherwise this is very very impressive, really.

Thanks for this piece and the useful queries set out so clearly by Salim Lennox. The latter is correct to link the new authoritatrinism of wokery with the left (especially in the USA with its unending capacity to re-vamp inividualism and commodify it for profit) as well as to distrust the far right and point up that Nazism was not a product of the Enlightenment. None of us need to idealise the latter but we can defend some principles of universalism in its wake. These include the defence of freedom of expression for all, which remember not too long ago was a purportedly a priority of the left in the USA. This has now flipped into reverse, so that bullying and silencing have been converted into virtues in all spheres of corporate capitalism, state run bureaucracies and third sector organisations, in the name of immediate social progress. Because the left have sold their heads to wokery, being on the left and being a democratic socialist or an anarchist have become disconnected in practice. This is a depressing scenario especially in relation to gender politics, which is a black hole everyone is falling into, while genuine redistribution has been abandoned and the planet gets hotter and hotter. Nancy Fraser has been commenting on this scenario for over 20 years. More heat than light continues to grow in all senses of this term. My take on all this is offered in Identity Politics; Where Did It all Go Wrong? (Phoenix Books, 2022). See also I'll Burn That Bridge When I Get To It by Norman Finkelstein (Sublation Press, 2023) and The Politics of the Underclass by Loic Wacquant, especially his coda on race (Polity Press, 2023).