The Society of Conformism

Different Psychosocial Types of Conformism and the Failure of Critical Thinking

The last hundred years have been years of intense conflict that have resulted in countless wars, in addition to the two world wars. The classes and social groups that intervened in these conflicts did so in the name of objectives so broad that they did not allow for an easy connection with the concrete individuals who fought in these conflicts and for which they often gave their lives. Goals such as nationalism, internationalism, revolution, socialism, racial superiority and the civilizing mission were the ultimate expression of non-conformity and always presupposed bodies that in the name of such goals would suspend their normal lives to fight against the status quo. Many millions would never return to normal life. Perhaps less noticed, this period was also the scene of another phenomenon that is reaching alarming proportions today: there are individuals who, for various reasons, are not interested in fighting the status quo or, if they are, they don’t have the conditions or legitimacy to do so. Whether they like it or not, they have to resign themselves to the consequences of what is happening: the world happens to them; there is nothing they can do to make it happen. There have been many types of individuals subjected to this condition. I will distinguish five because of their relevance today: the stranger, the maladjusted, the assimilated, the acedic, the obsolete.

The stranger

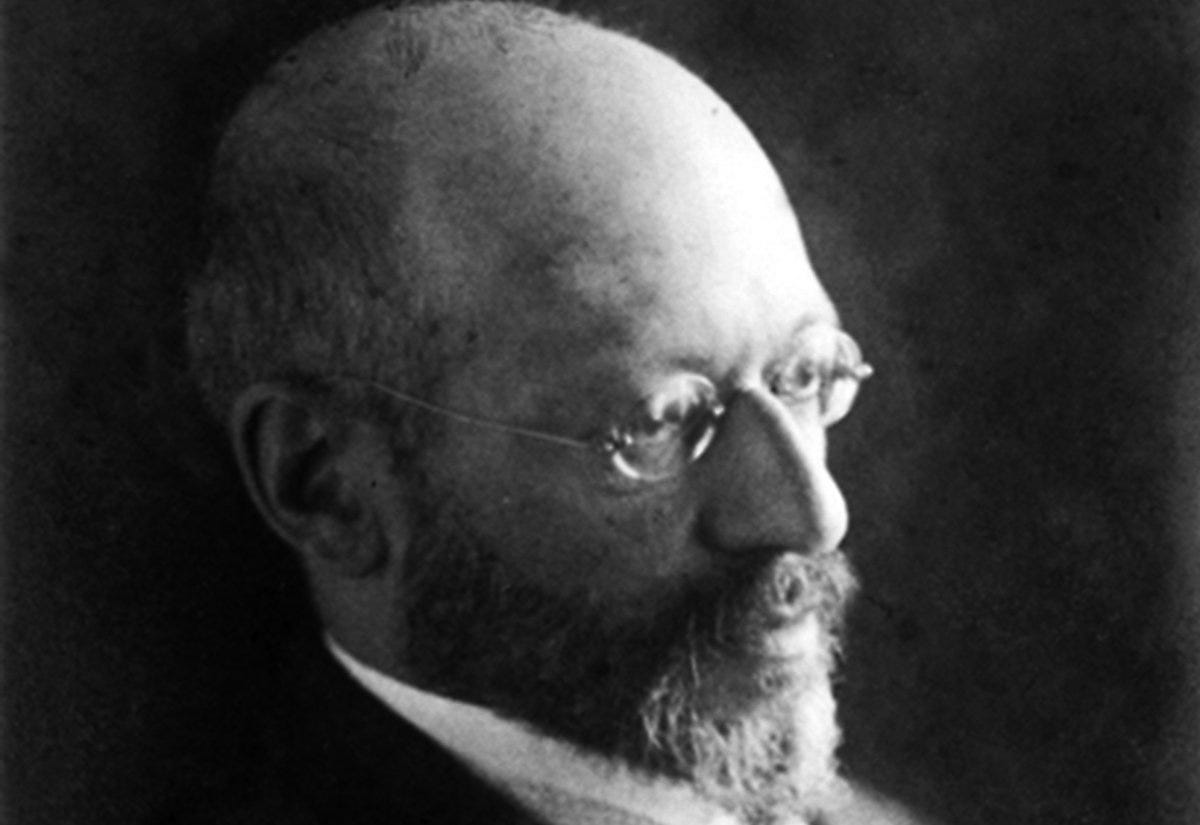

The German sociologist Georg Simmel dedicated an eloquent text to this figure. The stranger is someone who is among us, but doesn’t belong to society in the same way that “we do.” He is both near and far, inside and outside. You have to deal with him, but you don’t trust him. Simmel shows that, historically, the merchant was a stranger, someone with whom traditional society was in contact, but with whom it was not connected by stable ties of kinship, place of birth, occupation or culture. Simmel was Jewish and knew what he was talking about. He was referring exclusively to the European society of his time. The colonial world was outside his analysis, but it was there, as Tocqueville had warned us, that the true dimension of strangeness in European society could be assessed: the colonized was the paradigmatic stranger. Today, new types of individuals have joined the category of the stranger, the most important being the immigrant in the societies of the global North, the workers of the global South employed by the large multinational companies of the global North and, all over the world, the workers of the app economy, namely food delivery workers. We depend on all these people, sometimes intensely, but the intensity of the relationship ends the moment the relationship ends.

The relationship between stranger and neighbor changes with the changes in the construction of relationships of strangeness and closeness, and it doesn’t even cover all the nuances of relationships. For example, the intimate is the closest neighbor, while the neighbor in the biblical sense is the strangest of neighbors. Closeness, strangeness and intimacy are undergoing profound transformations today, especially due to the growing role of social networks in interpersonal relationships. The intimate may be someone with whom you share nothing but the words and pictures you exchange on your cell phone. The stranger is someone who the intimate agrees is hostile, unintelligible, an enemy, in short, someone who doesn’t belong, even if you need them. The maximum strangeness occurs when the stranger’s services are not even considered necessary because they are provided by new close ones, which social networks allow almost instantaneously.

The maladjusted

The issue of maladaptation to industrial society was one of the great themes of the first decades of the 20th century in Europe and the USA. Many will remember Charlie Chaplin’s film Les Temps Modernes. Industrial society brought with it an enormous acceleration of social life at all levels, not only in industrial work but also in mobility, interpersonal relationships, ways of living together, eating, talking, walking, and loving. This problem sparked passionate discussions and two main positions emerged. According to some, human nature was not infinitely flexible and industrial acceleration meant such violence to people’s physical-psychic metabolism that sooner or later the consequences would be evident, both interpersonally and socially. Democracy itself would eventually suffer. According to others, human nature was infinitely plastic and would easily adapt to new rhythms. After all, the Olympic Games were proof that humans were capable of surpassing all the limits previously considered insurmountable. It wasn’t a simple subject; it rather involved deep philosophical questions about human nature and the future of democracy. In the US, the Walter Lippman-John Dewey debate summarized well the two fundamental questions: the nature of human nature and the social function of democracy. Writing in 1922 on the new barriers that prevent citizens from gaining access to truth—mainly the news media—, Lippman criticized the “artificial censorships, limitations of social contact, the comparatively meager time available in each day for paying attention to public affairs, the distortion arising because events have to be compressed into very short messages and the difficulty of making a small vocabulary express a complicated world.” Basically in agreement on the diagnostics, Dewey was opposed to the reliance on experts compensating for the incapacities and irrationalities of human nature, the strength of collective and reflective intelligence, and the project of building deeper forms of participatory democracy. While the discussion was taking place, American society was changing rapidly and, in the midst of deep crises such as the Great Depression, it was leaving behind all those who were not allowed to adapt to modern times. John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath is a clear testimony to the internal trauma that occurred under the overwhelming slogan of progress.

The maladjusted were forgotten and only re-emerged in the struggle of African-Americans for civil rights , in the opposition to the Vietnam War, and in the hippie culture of the 1960s. The hippie movement was the counter-culture of the maladjusted; against war and competitiveness, the hippies opposed peace and love. But they were also the expression of a historical defeat. The version of the infinite ductility of human nature had triumphed and they were just a marginal cry, whose original subversive tone would end up being co-opted, becoming yet another production line for the emerging entertainment industry. This, by the way, was not the end of the maladaptation syndrome, it was its transformation from a political-cultural movement into a psychological problem. Solvent maladjusted now fill the offices of psychologists, psychiatrists, and psychoanalysts. The others fill prisons, drug recovery centers, and the streets of the homeless. They don’t necessarily conform to the world they live in, but they don’t imagine revolting because they don’t have the strength to do so, because they don’t even know what other possible world might be, or because they have a paralyzing fear, knowing the price you pay today for being nonconformist.

The assimilated

The category of the assimilated has colonial origins and was invented to designate that small group of colonized people who, through colonial education, abandoned (and rejected) the “savage culture” that had been passed down to them by their ancestors, learned the colonial language, culture and ways of living together, and behaved (in appearance, at least) as if they assumed the relationship of colonial domination to be natural. By definition, the assimilated person was not the same as the settler. They were an intermediate category between the “savage” and the “civilized European.” They had certain rights, as long as they conformed to the colonial status quo. With the independence of the colonies, this category disappeared. But it has somehow re-emerged in other forms, both in the global South and in the global North. In the global South, it is made up of the emerging globalized middle classes for whom traditional or ancestral culture governs the special rituals of collective life (weddings, funerals), but not much else. Not being governed by ancestral culture doesn’t mean that they don’t know and value it. They just think it’s out of step with “modern urban life,” i.e. Westernization. In this case, assimilation is a very complex phenomenon because it contains a healthy element of revolt against the elites who invoke traditional culture to cover up their corruption, incompetence, and privileges. The second case of assimilation is that of immigrants in the global North who lose or reject their original cultures in order to better adapt to a society that they know is hostile to them and will do anything to reject them. Assimilation here is the most psychologically tolerable form of conformism.

The acedic

The monk John Cassian, writing in the 5th century BC, was the first to draw attention to the psychological condition of many monks in Palestine, Syria and Egypt in the early days of Christianity, a condition he called acedia (from the Greek: akedia, indifference, absence of care). It was a state of permanent lethargy, inability to concentrate on study or worship, mental and spiritual exhaustion, apathy, melancholy, torpor, dispersion or loss of thought (theperuagatio cogitacionum of medieval rhetoric). Evagrius Ponticus called acedia the “midday demon,” because it was at midday that the monks were most restless in their cells, the day seemed to last fifty hours and their lives seemed to have no meaning. Cassian understood acedia to be the result of the monastic conditions of social isolation, spatial confinement and monastic silence, an enormous deprivation that contrasted with the immense task of getting closer to God. Later, acedia was converted into one of the seven deadly sins, laziness. But it was always much more than that. The acedic is the indifferent individual, not by cynical choice, but out of a deep sense of inability to transform the world. It is easy to assimilate acedia to burnout, to depression, just as in a previous period it was assimilated to ennui or Weltschmerz. But acedia is more than that. It’s an attempt by the so-called post-baby boomer generations (born between 1945 and 1964), i.e. the generation of millennials (born between January 1983 and December 1994) and generation Z (born between January 1995 and December 2003), to adapt to a disproportionate and even absurd world, whose irrationality, especially in ecological terms, is as dramatically experienced as the inability to fight it. The new generations are not reaching adulthood as quickly as their parents or with the same certainties. Humanity is no longer livable in the abstract, job insecurity weighs (sometimes heavily, sometimes lightly) on their choices and investment in education does not guarantee the kind of benefits it used to (job and career security). There is the will to give meaning to life to the exact extent that this will coincide with the ability to transform it. This capacity has a personal and interpersonal scale. Identity is a form of belonging which, because it is naturalized (gender, race), is easier to obtain and mobilize. The important thing is not to transform the world, but to eliminate enemies so that belonging is more recognized. Conformism stems from giving up on getting to the roots of modern domination: capitalism, colonialism, and patriarchy. Easy consensus for easy victories.

The obsolete

This vector of conformism is the most recent and stems from the development of so-called artificial intelligence (AI). AI refers to machines that perform cognitive tasks—such as thinking, understanding, solving problems, and making decisions—based on learning systems that are not explicitly programmed. The key element is the abundance of data (big data) and the algorithms that develop from it. The automation of tasks that today provide employment for humans is the best-known dimension of the transformations taking place under the impact of generative AI, i.e. AI that learns and corrects itself in ways unimaginable to humans (deep learning). Quite apart from employment, politics, love, religion, economics, art, communication, creativity, sexual activity—in other words, life in general—could be decided tomorrow by non-human means. While the industrial revolution created the problem of human maladaptation, the AI revolution creates the problem of human obsolescence. If we humans become obsolete, the problem no longer concerns conformism/nonconformism but functionality/dysfunctionality. The dysfunctional is not nonconformist; it is discarded noise. Some people think that nonconformism can be reinvented by AI, but no one can guarantee the ethical or political meaning of nonconformism. So much so that nonconformity can be aimed at destroying the human species.

When today the different psychosocial types of conformism are attributed to the failure of critical thinking, we need to reflect on whether it wasn’t modern Western thinking (critical and non-critical) that failed by splitting the links that united three fundamental modes of existence: the body, ethics, and transcendence.