The “West” is not just a term, but also a concept that acquires new meanings with time. To its advocates, it can be analogous to civilization and benevolent power; to its detractors, mostly in the “East” and “South,” it is associated with colonialism, unhinged violence, and underserved wealth.

The current, seismic shifts in world affairs, however—namely, the Russia-Ukraine war, and the budding conflict in the Strait of Taiwan—compels us to re-examine the “West,” not only as a historical concept, but also as a current and future idea.

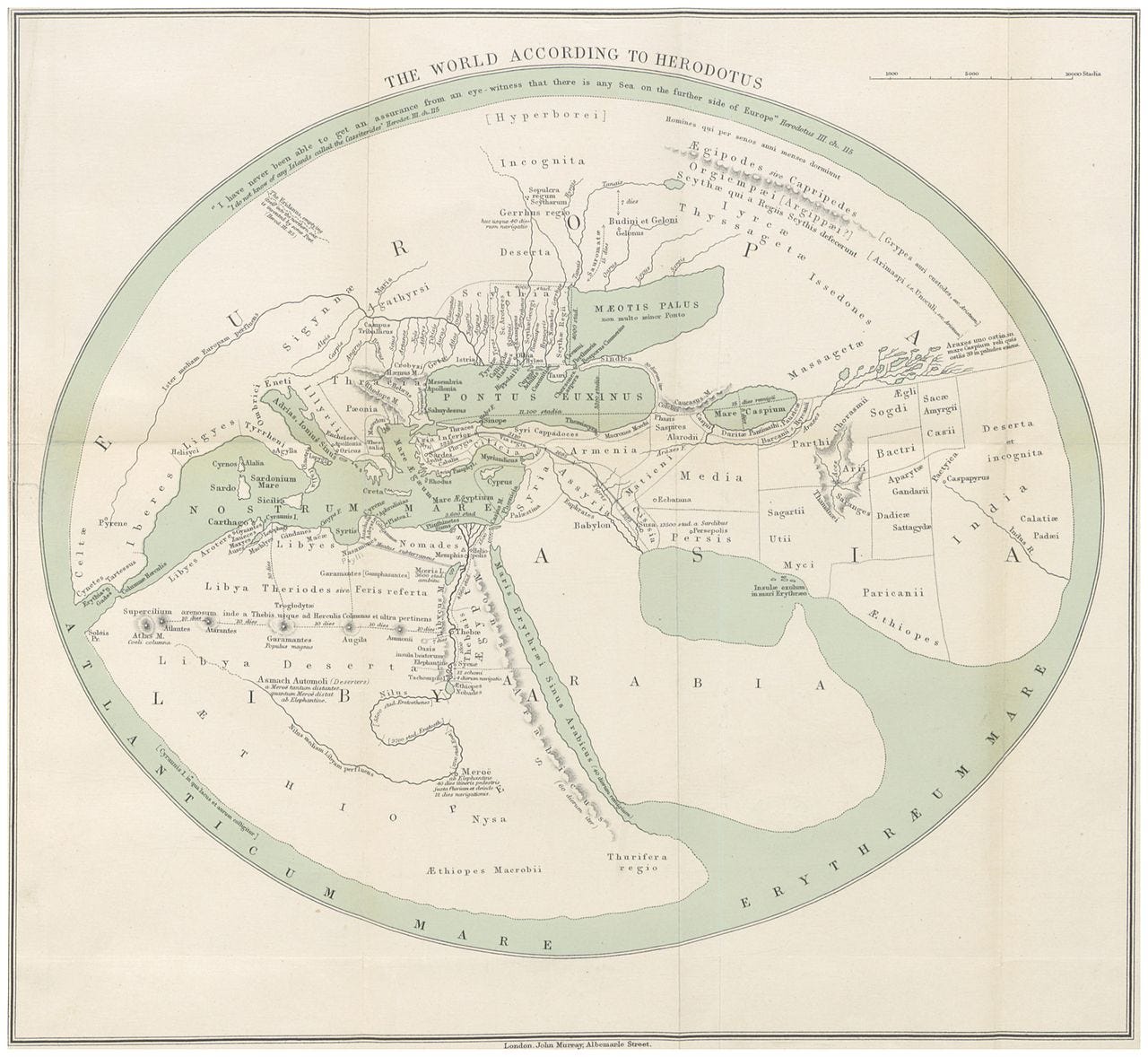

The ancient Greek historian and geographer Herodotus is often credited with the coinage of the term “West” in the 5th Century BC. The root causes of that coinage might have been mostly geographic. However, in the 11th Century, the division between West and East became decidedly geopolitical, when the center of power of the Catholic Church began shifting eastward, from Rome to Byzantium. While the Catholic Church represented the West, the Orthodox Church epitomized the East.

Of course, historical realities are never so simple, as history and its interpretations are written by individuals, with their own religious, nationalistic, and regional biases. Those who lived in the “East” obviously had no choice over the matter, the same way as those living in today's “Middle East,” for example, were hardly consulted before Western colonial powers tailored the world's geography to represent “regions of influence,” and the proximity of these regions from the centers of Western empires—London, Paris, Madrid and so on.

In the “Global South,” the West is hardly geography, but an idea and, quite often, a bad one. For the South, the West means economic exploitation, political meddling and, at times, military interventions. Southern intelligentsias are often divided between the need to “westernise” and their justifiable fear of “westernisation.” In countries like Nigeria, the “discussion” often takes violent turns. The name of the militant group Boko Haram translates to something like “Western education is forbidden.”

Of course, the West is far more encompassing than geography. At times, the connotation seems purely political. Australia and New Zealand, for example, are “Western countries,” even though they are located in the geographical region of Oceania.

In the past, Washington even shifted the very meaning of the West to accommodate its sheer military interests. In January 2003, then-US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld used the term ‘Old Europe’ as opposed to “New Europe,” with reference to newly incorporated NATO members of Eastern Europe who conveniently supported his country’s invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan.

At times, the US was willing to cancel the very idea of the West and demarcate entirely new geopolitical lines. When, in 2009, US President George W. Bush declared before the Congress, “Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists,” he had, though temporarily, walked away from the West to whole new uncharted geopolitical territories.

That designation did not last for long, as the “war on terror” took a back seat to supposedly more imminent threats, China’s economic rise and Russia’s growing military might. For Washington, the “West” now simply means NATO, and nothing else.

The eagerness in US President Joe Biden was palpable on 9 August when he ratified the US government’s decision to approve the applications of Finland and Sweden to join NATO. “Our alliance is closer than ever. It is more united than ever and ... we'll be stronger than ever,” Biden declared. Ironically, only four years ago, it was Washington that seemed to be leading a political war on NATO, with then US President Donald Trump warning US allies of “grave consequences” if they did not ramp up their spending, and threatening that the US could “go our own way.”

Despite the over-emphasis on closeness, unity, and strength by the US, not all Western NATO members are participating in the American euphoria. The cracks of disunity among European countries—both western and eastern—continue to make daily news headlines. And while US weapons manufacturers and energy exporters are making outrageous profits as a direct outcome of the war in Ukraine, other Western economies are suffering.

Germany, for example, is heading for a recession as its economy is forecast to shrink by about 1% in 2023. In Italy, the energy crisis has worsened, with diesel and other fuel prices skyrocketing, affecting important sectors of the Italian economy. Other countries, especially in Eastern and Central Europe, for example Estonia and Lithuania, are to face a worse fate than those of their Western and more affluent counterparts.

It is obvious that not all Western countries are sharing the burden of the war or its astronomical profits, a reality that potentially could redefine the geopolitics of the West altogether. Yet, regardless of where the West is heading, there is no question that the East is finally rising, a momentous historical event that could reinforce whole new political geography, and likely alliances as well. This might also be the South’s opportunity to finally escape the West and its unyielding hegemony.