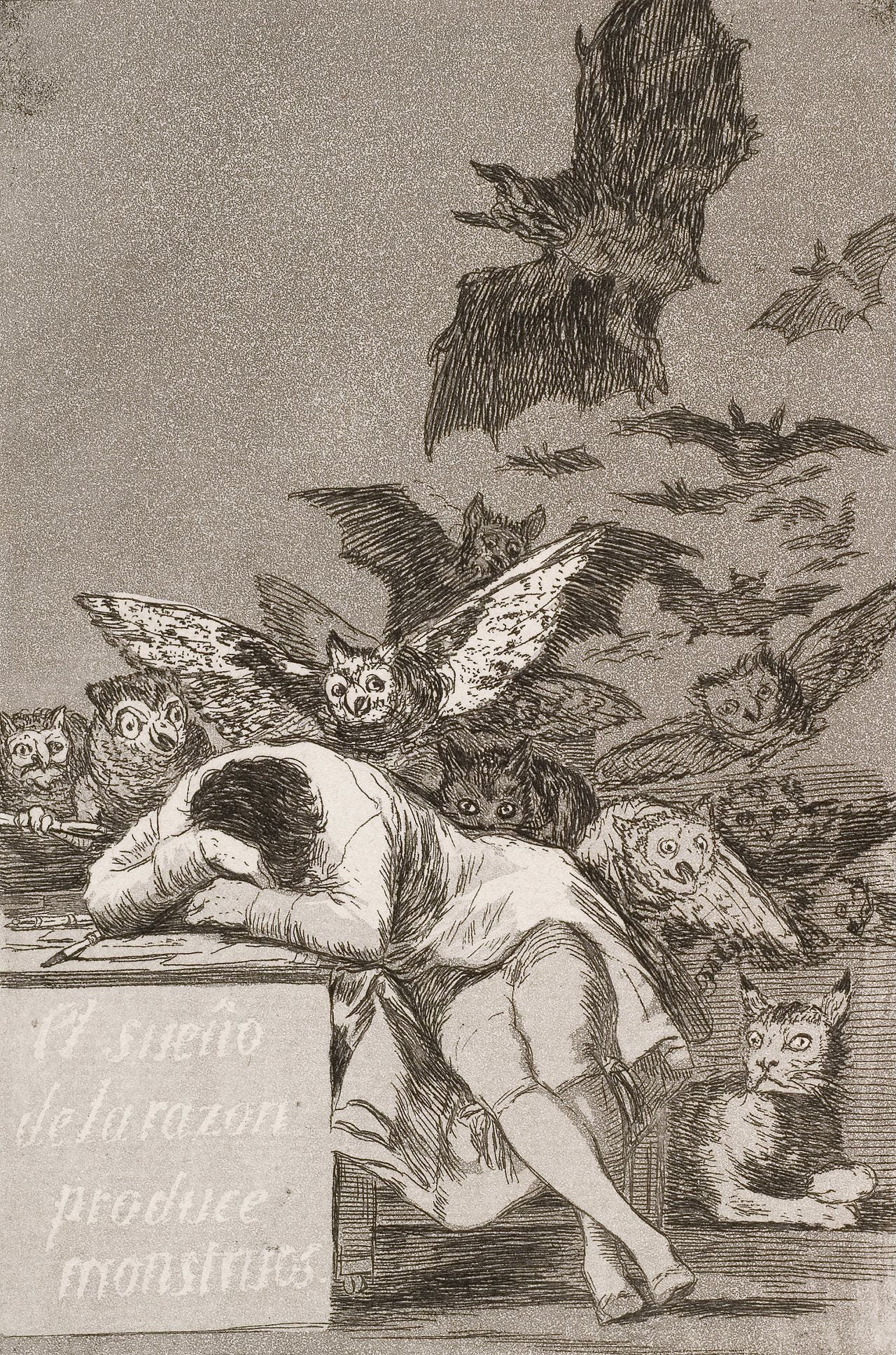

The world is moving inexorably towards war. Any imaginary poll of the world’s population would show that nobody wants war. But war will probably break out before the end of the decade. Most countries in the world claim to have democratic regimes, but no party with any electoral significance, from left to right, considers war an imminent danger and takes up the fight for peace as its main banner. Peace doesn’t win votes. War brings dead people and dead people don’t vote. No party can imagine carrying out electoral propaganda in cemeteries or mass graves. Nor does it imagine that without the living there are no parties. All this seems absurd, but absurdity happens when reason sleeps, as Francisco de Goya warned us 225 years ago in his aquatint El sueño de la razón produce monstruos. We don’t need to go that far back.

The lessons (or illusions) of history

Let’s go back to 1900. England was then the most powerful country in the world. But as every apogee means the beginning of decline, the peaceful competition of the US was beginning to be feared. Economic growth in the US was vertiginous, the latest inventions of the industrial revolution were taking place there and, among the many advantages over Europe, one was particularly precious: the US spent very little money on weapons. According to reports at the time, a country of 75 million inhabitants had an army of 25,000 men and a ridiculous defense budget for a country of that size. On the other hand, the most developed European countries (England, Germany and France) were in increasingly fierce competition with each other over colonial sharing and industrial superiority (Germany was increasingly in the spotlight) and were entering the arms race. In addition, between 1899 and 1902, England was fighting a sordid colonial war against the Boers in South Africa. At stake was the control of gold production and Cecil Rhodes’ imperial dream: from the railroad between Cape Town and Cairo to total control of the world so that “wars would become impossible for the good of mankind”. Imperial capitalist domination demanded war and the arms race, allegedly to make war impossible in the future. Are there any similarities with the current war speeches of the US and the European Union to defeat Russia and China? There are, but there are differences.

In the first decade of the 20th century, two movements were visible: one in public opinion and the other in business. Public opinion was dominated by an apology for peace against the dangers of a war that would be fatally deadly. The 20th century was to be the century of peace, without which the prosperity that was being announced would not be possible. In 1899, the first International Peace Conference was held in The Hague and, the following year, there was the World Peace Congress. From then on, there were many international congresses and meetings on peace. It was deplored that international cooperation was deepening in all areas (postal services, railways, etc.) except politics. Between 1893 and 1912, 25 books were published against the arms race. Who is Who in the Peace Movement was widely published. Recent inventions in war material (smokeless gunpowder, rapid-fire rifles, explosive substances such as lyddite, melinite and nitroglycerine, etc.) were said to make war not only very deadly, but impossible to win for either side in the conflict. War would always end in a stalemate and after much death and devastation. A journalist from the English Echo resigned from the paper so that he wouldn’t have to defend the war against the Boers, and 200 high-profile English intellectuals organized a dinner in his honor. Between 1900 and 1910, more than a thousand pacifist congresses were held: workers, anarchists, socialists, freethinkers, Esperantists, women. The growth of democracy in Europe and the USA was said to be incompatible with war and that the large number of arbitration agreements was the best demonstration of this. The Russian sociologist Jakov Novikov demonstrated that the well-being of the masses had never improved with the wars, quite the opposite. People wrote about “the illusion of war” and the publications sold many thousands of copies.

There was a current of opinion that the real illusion would be the “illusion of peace” if the struggle were not reoriented against capitalism. If this didn’t happen, war would be inevitable. This was the position of socialists, anarchists, and the workers’ movement, which socialists and anarchists sought to control. War was the great obstacle to social revolution. The general strike and the refusal of military service were two of the most frequently mentioned forms of struggle.

But the world of public opinion was one thing and the world of business was another. In the business world, since 1899 the arms race had been advancing at a rapid but discreet pace. At the 1907 International Workers’ Congress in Stuttgart, Karl Liebknecht revealed the extraordinary growth in arms spending, which meant that countries were in fact preparing for war. The profits of the big arms companies reflected this: Krupp in Germany, Vickers-Armstrong in England, Schneider-Creusot in France, Cockerill in Belgium, Skoda in Bohemia and Putilov in Russia. It was clear that the accumulation of weapons would lead to war. In fact, the big companies were beginning to use a new propaganda weapon: paying journalists and newspaper owners to publish fake news about the growing armament of their probable opponents in the coming war in order to justify spending more on weapons. Sounds familiar to today’s ears? Yes, but there are differences and for the worse, much worse.

The socialists were right: the fight is against capitalism

The apogee of US-led global capitalism came in 1991 with the end of the Soviet Bloc. Just like a hundred years before, the apogee of the most powerful power meant the beginning of its decline. And just as before, the most profitable industry in periods of decline is the one that produces goods whose use consists of destroying and being destroyed. Such goods have to be ceaselessly replaced by others for as long as the war lasts. The longer the war lasts, the greater the profits. Eternal war is therefore the most profitable. Now the big arms companies are no longer European, they are American, and the US, unlike a hundred years ago, is by far the country that spends the most on armaments and therefore has the greatest need to use them (that is, to use by destroying and replacing). The US spends a trillion dollars on armaments, but it’s certainly not enough because war entrepreneurs invent disadvantages for the US in relation to its enemies which have to be overcome promptly.

The struggle for peace is now more than ever a struggle against capitalism. Why more than ever? If, in the wake of Immanuel Wallerstein, we take the world as a unit of analysis, we can say that between 1917 and 1991 the world experienced a period of intense transnational civil war. It was a civil war because it took place within a single system – the modern world system. Although globally dominant, capitalism had to contend with another strongly competing economic system, state socialism, whose influence extended far beyond the Soviet Union. This civil war was fought by multiple means, including counter-insurgency, development aid to dependent countries and proxy wars (Korean War, Vietnam War, etc.).

The Second World War was a period of calm in this civil war, since the USA and the USSR were allies against German Nazism. With the end of the Soviet Union and the transformations that had taken place in China in the meantime, which would integrate the Chinese economy into the world capitalist economy, albeit with some specificities (maintaining national control of financial capital), the transnational civil war between capitalism and socialism ended. There was an interregnum, which lasted just over ten years, in which Russia was a capitalist country of intermediate development like any other and China was an economic partner, also of intermediate development, but with strategic value for US multinational companies bent on the monopolistic conquest of the world.

After the global financial crisis of 2008, a new transnational civil war began, this time between the capitalism of US multinationals and the state capitalism of China. In order to neutralize China, it was necessary to block its access to Europe for two reasons: Europe was, alongside the US, the other major affluent consumer in the world; through cooperation with China, Europe could have some claim to escape the increasingly evident decline of the US in the world economy and become an additional factor of competition and weakness for the US. In order to block China’s access to Europe and subject the latter to the US, it was necessary to separate Europe politically and economically from Russia (whose territory is mostly in Europe). Russia, with its thousands of kilometers of borders with China, is not only China’s access route to Europe, but also the strategic territory of Eurasia. The idea that whoever controls Eurasia controls the world has been around for a long time. This has led to a new transnational civil war, the first proxy wars of which are the Russia-Ukraine war and the Israel-Palestine war.

This civil war is totally different from the previous one. In the previous one, the struggle was between two economic systems (capitalism versus socialism), while now it is between two versions of the same economic system (multinational capitalism versus state capitalism). Nothing guarantees that this war will be less violent than the previous one. On the contrary, as we have seen, at the beginning of the 20th century, the dispute took place between countries with a long common past located in a small corner of Eurasia. Today, it is a struggle for global domination that extends beyond the planet. Monopoly capitalism was born in 1900 when US financial capital began to expand into railroads and from there into many other sectors and, potentially, into every country in the world.

For monopoly capitalism, the idea of a multipolar world is as threatening as the idea of competition with other economic systems, and the same destructive drive is present in both cases. What’s more, the potential and degree of destruction are now immensely greater than before. I’m not referring to the existence of nuclear weapons, a life-destroying technological innovation that makes the preoccupation of commentators at the beginning of the last century with the warlike inventions of their time ridiculous. I’m talking about the nature of today’s global capitalism and (dis)governance, and the emergence of two of its consequences. We are entering an era in which forms of potentially destructive power without limits are strong enough to neutralize, circumvent or eliminate any democratic process that seeks to put limits on them.

Global techno-fascism: Elon Musk

At the beginning of the 20th century, we saw that the struggle for peace and the peaceful resolution of conflicts saw sovereign states as the units of analysis and the privileged political actors. We know that sovereignty was an abstract good that only the most developed countries could really enjoy, and that much of the world was subject to colonialism or the tutelary influence of Europe. Today, however, technological development, neoliberal globalization and the concentration of wealth mean that the power to control human and non-human life is no longer subject to democratic scrutiny. At the beginning of the 20th century, the illusion of peace was based on the rise and strengthening of democratic governments. After all, democracy was based on replacing enemies to be defeated by war with political opponents to be defeated by voting. Hence the mobilizing capacity of the fight for suffrage. For many, democracy had the capacity not only to promote the peaceful resolution of conflicts, but also to regulate capitalism in order to neutralize its “excesses”.

Today, most national governments consider themselves democratic, but democracy, if it was ever capable of regulating capitalism in any country, is now strictly regulated by it, and is only tolerated insofar as it is functional for the infinite expansion of capitalist accumulation. Undoubtedly, the most powerful national states continue to exercise formal power, but the real power that controls their decisions is concentrated in a very small number of plutocrats, some with their faces blatantly visible, others, the majority, faceless. Real power is enhanced to an extent that is hard to imagine by a toxic fusion of the technological capacity to control the human life of vast populations down to the smallest detail and regardless of their nationality, with the financial capacity to buy, co-opt, blackmail or obliterate any obstacle to its purposes of domination.

This is a new kind of fascist power, a global techno-fascism that knows no national boundaries. Elon Musk is the metaphor for this new type of power. Unlike Adolf Hitler or Benito Mussolini, Musk’s specific personality, although repugnant, is of little importance, since what matters is the power structure that he commands today and that tomorrow may be commanded by another individual. The strength of this new global techno-fascism is well expressed in the worldwide dramatization of the struggle of a relatively powerful national state against a simple foreign individual simply because he is a global techno-fascist. When, on 31 August of this year, the X network was suspended in Brazil by a decision of the Supreme Court because its owner refused to delete accounts on the network that reached millions of people and whose content spread fake news, seriously violated the most basic democratic values and incited hatred, violence and even murder, it was news all over the world. Was it imaginable ten years ago that a lone individual, and a foreigner at that, could afront a sovereign state?

Global techno-terrorism: from the Trojan Horse to killer pagers

On 18 September, thousands of pagers and walkie-talkies exploded in Lebanon, killing dozens of people (including children) and injuring thousands. These transmitters had been bought by Hezbollah apparently because they are secure devices that allow communications without locating the users. This terrorist act has been attributed to Israel’s secret services and its origin was the implantation of an explosive substance next to the battery, coded to explode by remote control.

The killer pagers are not just a new edition of the Trojan Horse, the huge hollow wooden horse built by the Greeks to enter Troy during the Trojan War. The horse was built by Epeius, a master carpenter and boxer. The Greeks, pretending to abandon the war, sailed to the nearby island of Tenedos, leaving behind the false deserter Sinon, who persuaded the Trojans that the horse was an offering to Athena (goddess of war) that would make Troy impregnable. Despite warnings from Laocoon and Cassandra, the horse was taken inside the city gates. That night, Greek warriors got off the horse and opened the gates to let the Greek army in. The story is told in detail in Book II of the Aeneid.

The similarity between the Trojan Horse and the killer pagers lies only in the fact that the term “Trojan Horse” has come to designate subversion introduced from the outside. The visibility and transparency of the device, embodied in an object that was not in common use, prevented it from being realistically reproduced (if ever) effectively in the future. On the contrary, killer pagers signify a qualitative change in the technology of war and population control. The same technology and the same murderous complicity that insidiously installed explosive material in these devices could tomorrow install in any other electronic device (cell phone or computer) any substance that, instead of killing, might damage the health, create panic or alter the behavior of its user, without any possibility of control by the user. With the development and spread of artificial intelligence, any everyday device can be used for this purpose, whether it’s a car or a microwave.

The international conventions against terrorism, which the Gaza genocide reduced to a dead letter, will no longer even make sense in the future when any citizen not fighting in any war is condemned to live in a society in which the most trivial act of consumption can bring with it, in addition to the guarantee and the expiry date, your death certificate, your certificate of mental insanity or your compulsion to commit a crime.

The international division of the labor of war and Cassandra’s curse

In an environment of global techno-fascism and techno-terrorism, Euro-North American capitalism is actively preparing to move from cold war to hot war. Faced with the blank or revoltingly impotent gaze of its citizens, a strange international division of the work of killing is being prepared: Europe will take care of beating Russia while the US will take care of beating China. At almost the same time, the European Union’s first defense commissioner, Andrius Kubilius, former prime minister of Lithuania, says that Europe must be prepared for war with Russia in 6-8 years, and a high-ranking US Navy officer declares that the US must be prepared for war with China in 2027.

There is little point in predicting that the war will take place, but that its outcome will be very different from what is imagined by these war entrepreneurs intoxicated by the think tanks financed by arms producers. Cassandra’s curse hangs over the few who dare to see what is obvious.