It has become common fare to read ghoulish stories of child abuse in institutions supposedly created to care for the vulnerable. Orphanages, homes, and religious orders have tended to feature, along with their assortments of innumerable sadists and paederasts. But in December, another institution caused ripples for its alleged role in abusing children.

A Danish Radio documentary series, The Search for Myself, did not hold back in levelling claims against the US Central Intelligence Agency that it had financially aided experiments on 311 Danish children in the early 1960s. A good number of them were orphans or adopted, making them ideal subjects.

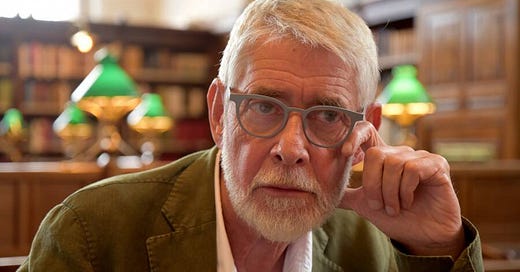

One such victim was the documentary maker Per Wennick, who claims that he was subjected to tests with no knowledge of their background in the basement of the Municipal Hospital in Copenhagen. These were supposedly designed to investigate links between heredity and environmental factors in engendering schizophrenia, work inspired by the psychologist Sarnoff A. Mednick.

Of particular interest in the experiment in question were the children of schizophrenic mothers. Of the 311 children in question, 207 had such mothers, while the rest, who constituted the control group, did not. Wennick was of the latter group.

As with previous experiments of such ilk, Wennick received shallow enticements without information. It was not difficult to convince him: he was 11, having grown up in the Godthåb orphanage with, he quipped, God and flogging. He was promised something exciting at the Municipal Hospital. For the pleasure of it all, he would receive 16 kroner. He sat in a chair, had headphones placed upon him, and was subjected to statements, screams and noises designed to frighten. Electrodes were placed upon his body, his heart rate, body temperature and sweat level measured.

Interest from US authorities was piqued given the attractiveness of Denmark’s central population register, something lacking in the US. The register enabled a tracking of individuals through the course of their lives and led to a lengthy collaboration between Mednick and the Danish professor based at the Municipal Hospital, Fini Schulsinger.

The latter would make much use of the project in his 1977 doctoral dissertation. Unusually, Schulsinger’s thesis was not subject to the usual public defence, with the Ministry of Justice permitting it to be held behind closed doors. The reasons were both disingenuous and dishonourable: preserving the anonymity of the children being used and ensuring their ignorance as to why they were being used as participants.

Till now, Schulsinger’s contributions as founder and director of the Psykologisk Institut at that hospital have been acknowledged with some admiration, with one author claiming he “made important contributions to the understanding of nature-nurture problems within psychiatry.” This clearly did not include the field of medical ethics.

The program Wennick participated in was almost certainly a violation of the Nuremberg Code of 1947, which stipulates that “The voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential.” Consent can only be ethically obtained where the person has the legal capacity to do so, has the exercise of free power of choice, and has “sufficient knowledge and comprehension of the elements of the subject matter involved as to enable them to make an understanding and enlightened decision.”

Disturbingly for Wennick, he remained a subject of interest for decades. In 1974, he participated in what he thought was the last trial but received no answer on what sort of research was being conducted. A decade later, seeking treatment for a skin condition in hospital, he discovered that he was the subject of interest to psychologists each and every time he used the health system. “I think,” he reflected, “that this is a violation of my human rights as a citizen of this society.”

An important source of funding for the Municipal Hospital project, supplied under the auspices of US health care, was the Human Ecology Fund, a CIA front overseen by Cornell University Medical School neurologist Harold Wolff. The Fund, which supplied the Danish program some $21,000, proved a vital source for underwriting research projects to better inform the agency about the use of torture and interrogation techniques.

The overall thrust of such programs lays in the realm of behavioural control, something which sprung from a concern that various powers in the Soviet bloc had used drugs or brainwashing techniques to conquer the human mind. By January 1952, the CIA had developed an offensive approach under the Artichoke program, described in a memorandum as “the evaluation and development of any method by which we can get information from a person against his will and without his knowledge.” Research institutions were duly co-opted in this enterprise.

Caught unawares by rude revelations that they had been duped, unwitting CIA grant recipients Alan Howard and Robert Scott could only rue the circumstances and suggest that their work had been noble, despite the ethically grubby source of funding. “All our contributions to the health and welfare literature have been written with the goal of alleviating human suffering, not using it to gain hegemonic advantage.” Academics and researchers can be such blithely ignorant creatures.

This has been a delicious revelation in the human rights propaganda wars fed by the Biden Administration in its battles against authoritarian demons and abusive bogeymen. (National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan dramatically, and offputtingly, describes human rights as “written deep in our country’s bones.”) The Chinese Foreign Ministry was delighted in turning the tables on such habitual cant, drawing upon the CIA-Danish project. In January, foreign ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian pointedly remarked that the US both apologise and offer compensation to the victims of such “secret experiments.”

Such compensation would lead to a hefty bill for the US treasury. For decades, unethical and illegal experiments have been conducted by US authorities upon unsuspecting citizens, often the most vulnerable. These have included infecting mental patients with hepatitis in Middleton and Norwich, Connecticut during the 1940s, nasally delivering the Asian pandemic flu to prisoners at Patuxent prison in Jessup, Maryland in 1957, and injecting cancer cells into chronically ill subjects at the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital in Brooklyn, New York in the 1960s. Any anthology of these ills would be weighty indeed.

Such practices pre-date the medical atrocities committed by Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan conducted during the Second World War. In 1932, the Tuskegee Institute, working with the US Public Health Service, commenced work on the natural history of syphilis that would do much to foster perennial suspicion of public health authorities and their ignoble intentions. The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male began with 600 Black men, 399 with syphilis, 201 without. Informed consent was not sought, the men being told that they were being treated for “bad blood.” Incentives were offered to the participants: free meals, burial insurance, gratis medical exams.

It took four decades before an advisory panel established by the Assistant Secretary for Health and Scientific Affairs found, with few traces of indignation, that the study had been “ethically unjustified,” yielding results “disproportionately meagre compared with known risks to human subjects involved.”

Wishing to be a true international citizen in such matters, the US imperium proceeded to expand such experiments beyond its shores. In 1946, the US government was involved in medical trials affecting at least 5,128 unconsenting and uninformed Guatemalans, including children, orphans, child and adult prostitutes, leprosy patients, prisoners, soldiers, mental patients and Guatemalan Indians.

Of these, some 1,308 were infected with syphilis, gonorrhoea and chancroid. Others had serology tests conducted upon them. “The researchers,” write Michael A. Rodriguez and Robert García, “systematically and repeatedly violated profoundly vulnerable individuals, some in the saddest and most despairing states, and grievously aggravated their suffering.”

A subsequent report on the experiments by the Guatemalan government, Consentir el Daño: Experimentos Médicos de Estados Unidos en Guatemala (To Agree to the Harm: Medical Experiments by the United States in Guatemala) found that such acts constituted “a crime against humanity.” The US Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues shied away from such language in its two reports but conceded that the experiments would be “impossible” to conduct under current ethical frameworks.

The response from Washington to the survivors of the CIA-funded program at Copenhagen’s Municipal Hospital is unlikely to be much more than a barely audible apology. Wennick and his similarly abused compatriots are probably best off focusing their interest closer to home, targeting the connivance and complicity of those Danish officials who enabled this sordid enterprise to go ahead in the first place.