Ambivalence is the way we recognize that someone or something has become significant to us.

—Adam Phillips

What do we inherit from the world and what can (and should) we change? Let us assume for the sake of it that three rough political positions exist in relation to this question: the revolutionary, the conservative and the reactionary. The revolutionary is determined, on the one hand, that everything that currently exists is wrong, and, on the other, that everything must be different. The conservative is more-or-less happy with things as they are, and demands only slow, piecemeal changes. The reactionary proposes a “return” to some earlier position, which may or may not, in fact, have ever existed.

All three positions presuppose a different relation to time and history—to abolish existing time and history, to accept time and history as it is (or was), or to reverse time and history. These approaches map on to certain psychological orientations, decisions, preconscious or otherwise, about the best mode or mood for politics—for the revolutionary, urgency, for the conservative, stasis (in the double sense of peace and civil war), and for the reactionary, nostalgia.

In In Defence of the Terror: Liberty or Death in the French Revolution (2003), Sophie Wahnich encapsulates this feeling of revolutionary urgency in the following way:

The Terror presupposed quick action so as to defeat the enemies before they destroyed the Revolution; so that the people would not be disgusted by injustice, and would not have to take up again for themselves “the sword of the law”; to spare the people from unheeding injustice in their exercise of the sovereign exception, and to effectively restrain this founding sovereignty. The exercise of Terror was thus a race against time.

This urgency for the revolutionary is also manifest in a potentially anti-social attitude, which is something akin to a kind of purist nihilism. As Sergey Nechayev puts it in “The Revolutionary Catechism”of 1869:

The revolutionary is a doomed man. He has no personal interests, no business affairs, no emotions, no attachments, no property, and no name. Everything in him is wholly absorbed in the single thought and the single passion for revolution. The revolutionary knows that in the very depths of his being, not only in words but also in deeds, he has broken all the bonds which tie him to the social order and the civilized world with all its laws, moralities, and customs, and with all its generally accepted conventions. He is their implacable enemy, and if he continues to live with them it is only in order to destroy them more speedily.

Sometimes, though, what looks like the desire to change the future, might itself be an attempt to arrest disaster. As Walter Benjamin states in 1940’s “Paralipomena to ‘On the Concept of History’”: “Marx says that revolutions are the locomotive of world history. But perhaps it is quite otherwise. Perhaps revolutions are an attempt by the passengers on this train—namely, the human race—to activate the emergency brake.”

The urgency felt by the revolutionary, that everything is wrong, that we are heading for disaster may well also encompass an emergency slowing-down, just as the reactionary might, on occasion, feel the need to speed things up. Where are we headed, after all? There is a sense in which we are already extinct—not only can we imagine the world without us (collective humanity), but we also live under the shadow of an extinction event (multiple, in fact) that we ourselves are perhaps already the author. There is barely time to tell the people that you love that you love them, let alone make amends for all the inequities of history.

But how can we tell today what is reactionary and what is revolutionary? Do these political appellations and oppositions even make sense anymore? There is an extent to which all political persuasions start to look meaningless in the face of everything that lies “outside” of politics, even for those who do not believe that there is an outside. To accuse the other of LARPing, of playing a role, in the theatre of politics, is a commonplace these days, a symptom not only of impotence in the face of decisions made, not by “a” or “the” people, but by others at some distance away, but also because technology has rendered “activism” virtual. Those who are volunteering, for religious reasons, or in their local community, are not as visible as someone launching an internet campaign to get someone fired for saying the wrong thing. Why does anybody stay online?

Do you ever just go outside and think, where is all this stuff happening? What is remotely real about any of this? In our everyday interactions with strangers, semi-strangers, acquaintances, friends, colleagues, there is no comparison with the vast majority of online behaviour. While internet activism sometimes has real-world effects, often hysterical and frequently negative, the slowness and complexity of normal life presents an entirely different prospect. We are operating on what Ivan Illich calls a “natural scale.”

“It is frequently argued that those who want equality want to change ‘the nature of man’.” Andrea Dworkin writes this sentence in Right-Wing Women: The Politics of Domesticated Females in 1983. Here she is channelling the US Right she is critiquing; this is their fear. But there are indeed “revolutionaries” who want to “change the nature of man,” which is to say, to alter humanity, either materially or ideologically, or both. There is, and perhaps always is, a war on nature—on our own as well as non-human nature. What of the revolutionary who wants to make better people through technology? To become engineers of human souls? Is it always reactionary to speak of “human nature”?

To invoke “nature” gives many people ostensibly on the left the heebie-jeebies—are you saying that there are essences? That we must just accept the hand nature (by which you really mean God) deals? But why would we ever give up on this discussion so that only those the left claims to oppose – conservative Christians, Aristotelians and hierarchists of all kinds – may have it? It hardly seems like an adequate starting point to imagine that we are only what we say we are, a linguistic squiggle in the air, or to imagine that we are unconstrained by corporeality. What would then differentiate the masturbation fantasy of a robot from the high-performance drug-induced crackpot-scheme of a Silicon Valley billionaire from a cry of despair in the face of an unbearable teenage embodiment?

So what (and who) can we really call “reactionary” today? The binary reactionary-revolutionary has been around since at least the mid-nineteenth century, with the French leading the charge against those who would seek to reinstate any aspect of pre-1789 thought. Monarchists, aristocrats, religious believers, property-owners, anyone who did not think that equality, liberty and fraternity were the necessary stuff of history were henceforth “on the wrong side” of it, and those that sought to enact these ideas by any means necessary were the righteous smashers of the clock in favour of a new conception of time. One can always say, though, that one is a “revolutionary” while, in fact, being entirely reactionary. Things that look new and shiny may in reality merely be the repetition of mistakes that humanity has already made multiple times, of errors that we have forgotten are errors. We have always been the same, even, or especially when we do not understand ourselves.

What would it mean today to “reclaim” reaction? Mary Harrington makes this move in a piece entitled “Reactionary Feminism” from June this year. She writes:

A reactionary feminism seeks to honor women by accepting as givens the things that make us human: our bodies and our relationships. It asks how we might frame our obligations justly, between the sexes, in the interest of the common good. Women must negotiate new social and economic conditions, not in a spirit of zero-sum conflict with men, but alongside our friends, husbands, fathers, brothers, and sons. The aim is not to return to some imagined perfect past, but to reach a future unshackled from the dystopian pursuit of progress. The only escape from a nightmare of atomization and war between the sexes is the recognition that we are embodied creatures, and that interdependence is not oppression but the very thing that makes us human.

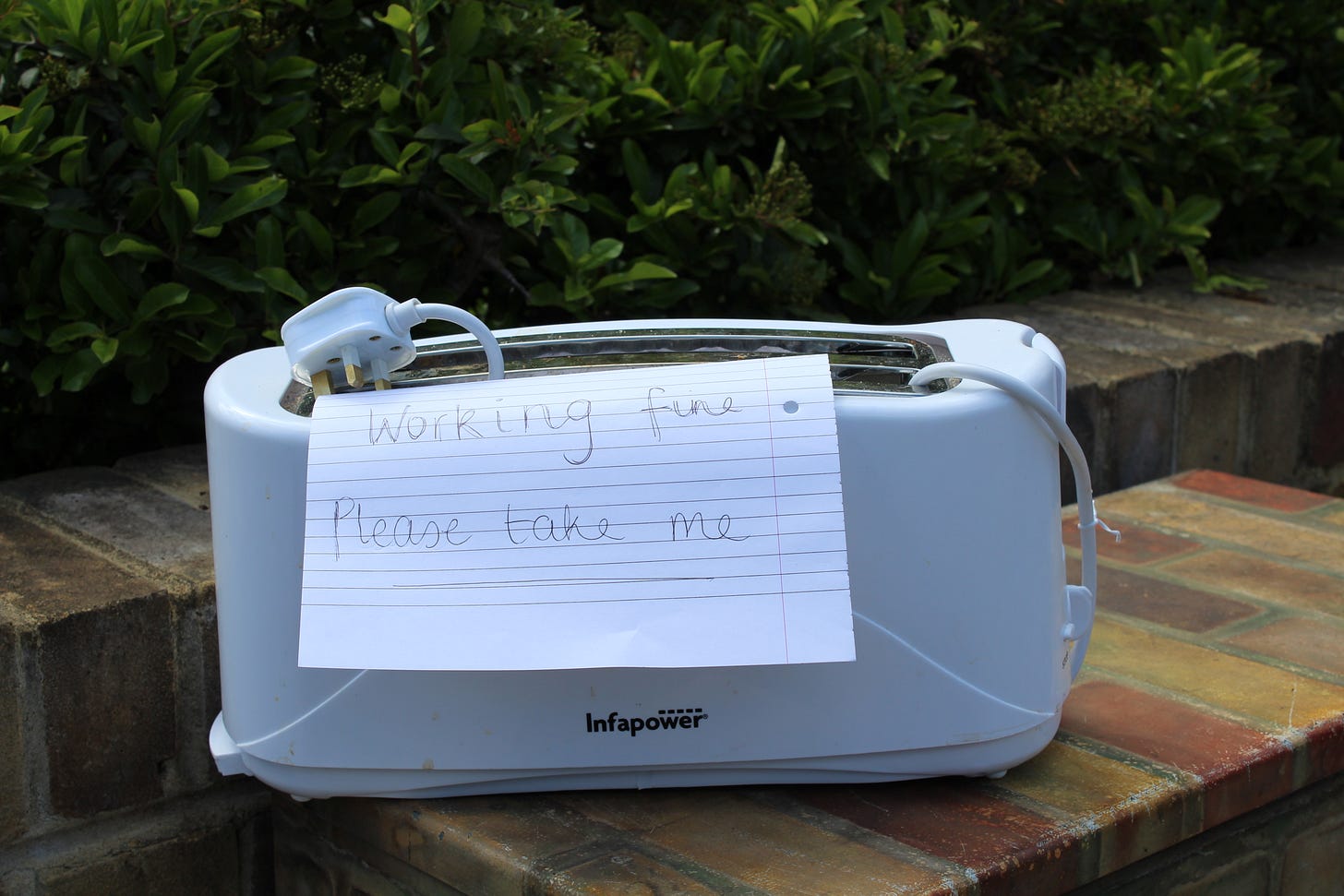

This “reactionary” feminism stands against the strain of contemporary “feminism” that suggests that men are always and implacably the enemy. It is anti-capitalist, insofar as capitalism contributes to a fantasy of progress, eternal growth, but in actuality is lived as atomisation, where increasingly virtual identities are stripped of any recognition beyond the flimsiest kind. There is a way of thinking about what matters, what is real, what we want to preserve, without barrelling headlong into a fully-automated hellworld. Look around. What is living and what is dead? This is a question worth asking quite literally.

Seeking virtue in the technological present is extremely dangerous: you will not be at the edge in even a short space of time, and will be back again with all the old realities. Arrogance is often a symptom of insecurity: but to imagine that the terminus of progress somehow resides in the present moment, and that history and our inheritances of all kinds, are merely to be disposed of, is itself a reactionary presentism. There is, in any case, no now, now, the instant always slides away – in this sense, anxiety is also a mood worth understanding, individually, collectively. Recall who you are. It is never too late to slam on the brakes.

I must be a conservative revolutionary to fit into this model.