Few would have staked their political fortune, let alone any other sort of reward, on a return of the British Conservatives on July 4. The polls often lie, but none suggested that outcome. The only question was the extent British voters would lacerate the Tories who have been in office for fourteen years, presiding over a country in divisive decline, aided by policies of austerity, the galloping cost of living and the lunatic tenures of Boris Johnson and Liz Truss. Predicted numbers varied from a return of 53 seats to what was forecast in the more accurate Ipsos exit poll of 131 seats.

As the night wore on, the laceration became a ballot massacre. It was clear that most voters were less keen on Sir Keir Starmer’s dour Labour team, supposedly reformed and devoid of dangerous daring, as they were of voting against the Tories. Any other option would do.

A whole brigade of senior Conservatives suffered a rout. Commons leader Penny Mordaunt lost her seat, as did defence secretary Grant Shapps. That manorial relic of Tory tradition and privilege, Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg, was also ousted from his seat. The Liberal Democrats made huge inroads into traditional Conservative territory, winning seats held by two former prime ministers—David Cameron and Theresa May.

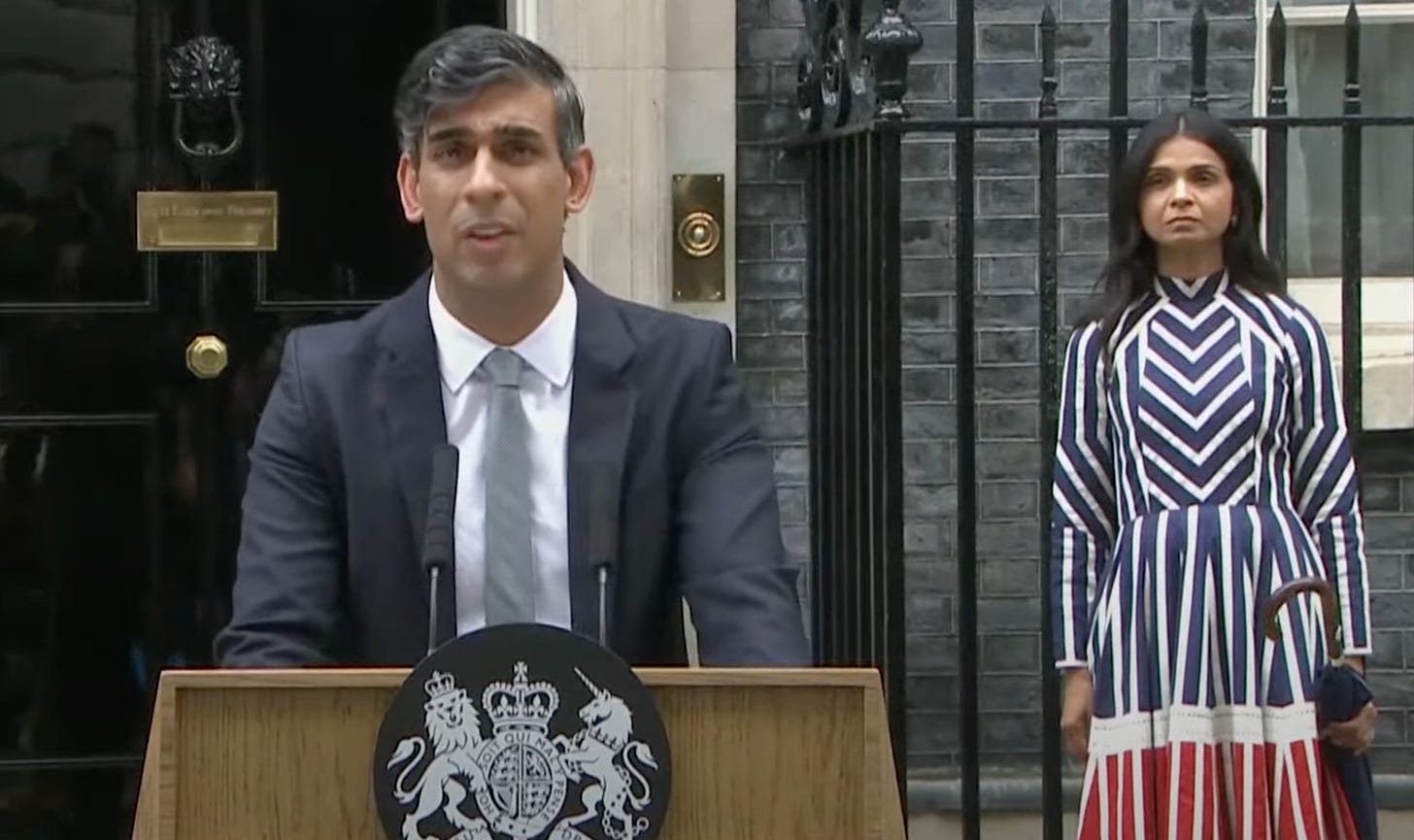

Recriminations, long readied in reserve, came out. Former party chair, Sir Brandon Lewis, pointed the finger to his leader, Rishi Sunak, whose decision to call the election was considered monumentally ill-judged. “I suspect right now that’s weighing on him very, very strongly … He will go down as the Conservative prime minister and leader who had the worst election result in over a century.”

Other Tories thought Sunak’s efforts to push the Conservatives further to the right to stem the leaching of votes to Nigel Farage’s Reform UK a serious error of judgment. Former Tory universities minister Lord Jo Johnson, also famed for being the sibling of that buffoonish wrecker-in-chief Boris, called efforts to make the Conservatives “a Reform-lite kind of party” a “big mistake”. Only a return to the “centre-ground of British politics” would spare them a lengthy spell in the wilderness.

The strafing of the more liberal Tory members does, however, place them in an unenviable position. Are they to, as Lord Johnson suggests, alter course to “appeal to metropolitan, open-minded, liberal voters”? Or should they, as Rees-Mogg insists, dig deeper into the soil of Conservative values, what he calls “core principles” that had been essentially pinched by Reform UK? Amidst the debate, former lord chancellor Robert Buckland could not resist quipping that this Conservative “Armageddon” was “going to be like a group of bald men fighting over a comb.”

The most staggering feature of these elections, leaving aside the ritualistic savaging of the Tories, was the wholly lopsided nature of the share of votes relative to the winning of seats. “This election,” the Electoral Reform Society solemnly declared, “saw Labour and the Conservatives receive their joint lowest vote share on record, with a combined 57.4%.”

That did not prevent the two major parties from snaring the lion’s share. Labour received 33.7% of the vote yet obtained 63.2% (411 seats) of the 650 on offer, making it the most disproportionate on record. The Tories, despite the bloodbath, could still count on 121 MPs with 23.7% of votes winning 18.6% of seats in the House of Commons.

The Lib Dems burgeoned in terms of representatives, gaining a record number of MPs (they now stand at 72), despite only having a vote share of 12.2%. It was a modest percentage hardly different from the 2019 election.

Reform UK, Farage’s rebranded party of Brexiteers, had every right to feel characteristically foiled by the first past the post system that is always defended by the party that wins majority, leaving smaller contenders to chew over its stunningly unrepresentative rationale. Having netted a higher percentage than the Lib Dems at 14.3% (over 4 million votes), they had only five MPs to show for it. “That is blatantly not a properly functioning democratic system—that is a flawed system,” a resentful Richard Tice of Reform remarked on BBC 4 Radio’s Today program. “The demands for change will grow and grow.”

The Greens, similarly, received 6.7% of the vote (just under 2 million), but returned a mere four MPs to Westminster. Despite this, the strategists will be seeing these wins, the most successful in their party’s history, as stunning, bettering the heroic if lonely exploits of Caroline Lucas. Tellingly, the party pinched two seats off Labour, and one from the Conservative stable.

Given that Labour proved the largest beneficiary of a voting system that should only ever apply in a two-way contest and given the prospect of Reform and the Greens posing ever greater threats from either wing of politics, appetite for electoral reform is likely to be suppressed.