Rwanda has become a curiosity as an African state. The mere mention of its name tugs the memory: colonial tragedy, ethnic violence, genocide. Then comes stable rule, for the most part. It is assured, iron fisted, and corporate. Since being elected in April 2000, the country has known one leader.

Paul Kagame has kept matters running as smoothly much like a well-oiled corporate machine, aided by his Rwandan Patriotic Front. At times, he treats his country as such. His model of economic inspiration is no less the city state of authoritarian Singapore, while such think tanks as the Heritage Foundation have found much to praise in terms of “economic freedom”.

The government also impressed officials at the World Bank sufficiently for Rwanda to be ranked above Switzerland and Japan in an Ease of Doing Business Report. The themes are development, returns, benefits, but the questions about how durable the modernisation program is, let alone how tangibly it deals with rural poverty and underdevelopment, remain.

While the Kagame regime is not quite the same as those inspired by the Chicago boys in the Chile of Augusto Pinochet—a monetarist playground of economic development overseen by a brutal authoritarian government—there are some parallels.

Dissenting troublemakers are to be hounded and Kagame’s opponents rarely end up well. As Michela Wrong has revealed with chilling precision, the president has shown lusty fondness in doing away with his rivals. Even former friends such as Rwanda’s former head of external intelligence, Patrick Karegeya, can be bumped off in retributive extrajudicial assassinations. (Karegeya’s murder in a hotel room in Johannesburg on January 1, 2014 delighted the then defence minister James Kabarebe: “When you choose to be a dog, you die like a dog, and the cleaners will wipe away the trash so that it does not stink for them.”)

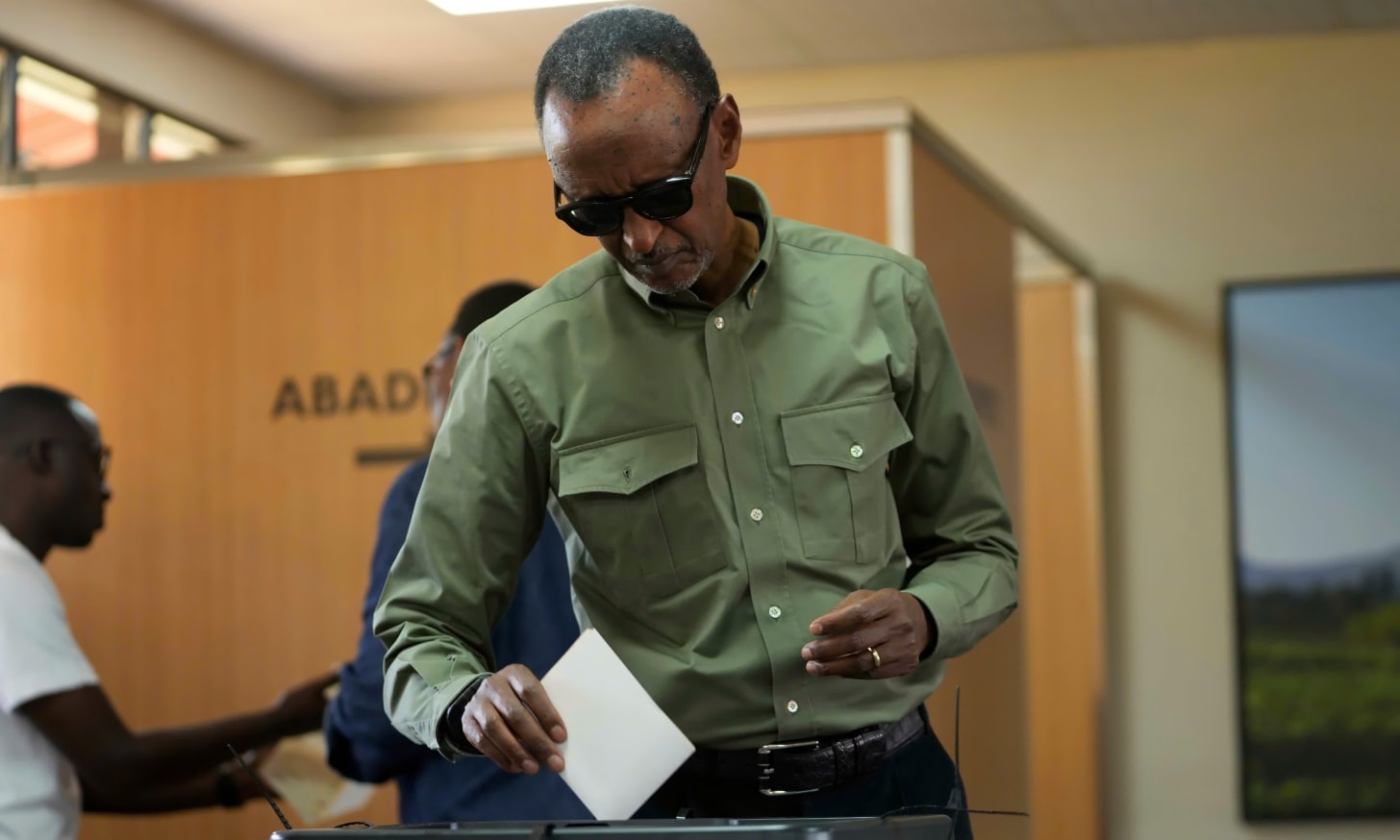

Any semblance of a viable opposition or boisterous civil society has ceased to exist and Kagame’s own wish to “join journalism in my old age”, expressed in April 2023, was barely credible. A far more accurate sentiment was expressed later regarding his intention to run in the July 15, 2024 election. “I would consider running for another 20 years. I have no problem with that. Elections are about people choosing.”

And some choice it turned out to be. Kagame eventually received the headshaking share of 99% of the vote. In the 53-seat Parliament, the Rwandan Patriotic Front secured 69% of the share.

Two candidates were permitted to challenge Kagame: Frank Habineza of the Democratic Green Democratic Party and Philippe Mpayimana, who counted as the token independent. Between them, they got 0.8% of the vote. Six other contenders had failed to cut the mustard for the electoral commission, which cited procedural grounds for barring them. Two opposition leaders suffered disqualification by virtue of having criminal convictions.

The Kagame government has spent much time exuding stability and reliability. It has contributed more troops than any other African state to the peacekeeping operations of the United Nations. It has held itself out, inaccurately and outrageously, as a safe third country to process unwanted asylum seekers and refugees, despite being itself the producer of asylum seekers. European governments have been particularly keen to overlook a tatty human rights record in that regard.

The regime’s copy book has been even more blotted of late. According to a UN report, some 3,000 to 4,000 Rwandan troops have been stationed in the neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo, aiding an insurgency led by the Tutsi-dominated M23 (Mouvement du 23 Mars) rebel group. (The M23 fighters have been in open rebellion in the eastern part of the DRC since late 2021.)

The summary of the report conveys the violent messiness of the conflict: “Heavy fighting continued between M23, alongside the Rwanda Defence Force (RDF), and the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of Congo (FARDC) together with the Wazalendo coalition of local armed groups, the sanctioned Forces démocratiques de libération du Rwanda (FDLR) and Burundi National Defence troops.”

The Ugandan military, deployed as part of a regional force in November 2022 intended to monitor a ceasefire with the M23, has shown itself to be strikingly ineffectual. In the solemn words of the UN experts, “Since the resurgence of the M23 crisis, Uganda has not prevented the presence of M23 and Rwanda Defence Force (RDF) troops on its territory or passage through it.”

Having laid waste to any viable, let alone sprouting opposition, the president has created conditions where any transition of power—when it comes—will be monstrously difficult. The shadow of the 1994 genocide is a long one indeed, and strong man politics is a perilous formula for a smooth succession. Whatever the broader stated goals of Kagame for his country, he remains motivated by a desire to preserve the position of the Tutsis, keeping the rival Hutus in check. Ethnicity, far from vanishing as a consideration, retains an aggressively beating heart.