If you’re caught in someone else’s fantasy, you’re fucked.

— Slavoj Žižek

The first iteration of the Woman Question, on the role of women in society, emerged alongside industrial capitalism, bourgeois liberalism, and the early expansion of the public sphere in the early 19th century. It touched multiple interrelated domains—legal, political, economic, educational, moral, and sexual. The very emergence of this question—alongside others like the Jewish Question and the “Negro” Question—revealed the contradictions and growing anxieties constitutive of modernity.1

Since the Enlightenment—and increasingly compounded by the shifting forces of industrial capitalism and empire—entire groups have been reframed as questions whenever their otherness, both real and imagined, disrupts the fantasy of social coherence. To be turned into a Question is to be rendered a mix of threat, nuisance, deviance, fascination, and opportunity. The group becomes a site of anxiety, enchantment, or perceived aberrance—one that must be studied, regulated, homogenised, and even eliminated. This gesture serves an ideological function: it displaces the structural contradictions of capitalist modernity onto scapegoated groups, allowing bourgeois society to imagine itself as a rational whole by projecting disorder elsewhere.

The best-case scenario for groups turned into questions is to be answered through reform, tolerance, or inclusion. In the worst, they are answered with elimination—via exclusion, incarceration, sterilisation, or extermination. Mediators—those who speak for, organise, or manage the group in question—often emerge from within it. Typically drawn from the more educated, middle- or upper-class strata, these figures attempt to define the desires, norms, and future of the collective. They both represent and discipline while conterminously modelling proper conduct and gatekeeping “relations” with other groups and the state. This positioning allows them to accrue both influence and income. Historically, these insiders-turned-arbiters have included the Talented Tenth2 for Black Americans and secular (often atheist) Zionists for Jews—each seeking to reshape their group in their own image in terms of conduct and aspirations.

Feminism, far from disrupting this ideological structure, follows the same pattern by amending the Woman Question with its own: the Patriarchy Question. The Woman Question has produced its own version of the Talented Tenth and Zionism—feminism. Feminists maintain their monopoly over the category “woman” by invoking The Patriarchy Question. The Patriarchy functions as adversary, alibi, and defence—especially against the Class Question.

Rather than liberate women from being a problem to be solved, feminism internalises the gesture and turns it inward: the ideal feminist becomes the standard against which all other women are measured—and found wanting. Feminist non-conforming women are re-cast as problems to be corrected, saved, or denounced in order to protect all women from The Patriarchy. The feminist desire ostensibly to liberate women has always doubled as a desire to change women—and feminists do not typically respond well when women resist their narratives, prohibitions, or instruction. All this from a movement that has long claimed to be born of from the ground up, highlighted as “grass-roots” for much of its history, while maintaining absolutely no accountability regarding who has created this internal political ethos of mandatory membership, much less why.

Similar to the groups that promote gender ideology and “trans rights,” the women’s movement and feminism have never been grassroots in origin. Each phase or wave of feminism has been led by a coterie of women—often backed by powerful benefactors—issuing population-level judgements about the sexes and projecting their own, typically bourgeois, experiences, neuroses, and desires onto “woman” as such.3

To liberate is to change—not only society, but also the group being freed from some constraint or barrier to entry. Liberation necessitates its opposite: a new regime, a new superego, a new normativity. The feminist project, to be successful, involves inculcating a new disciplinary regime of the self. The flip side of feminists’ Patriarchy fantasy is the fantasy of the “free woman”—the feminist ego-ideal.4

Feminists elevated their personal into the political, their biographical into cultural destiny. This translation is not itself illegitimate—that’s politics. The problem arises when those attempting to hegemonise the field of sexual politics and the category of “woman” behave as if they are not doing politics at all, but merely stating moral fact or correcting obvious injustice. This elevation of the feminist worldview to universal truth licenses them to dismiss or demean dissenters as deluded, damaged, or traitorous. And to those who fall outside the sacrosanct category of woman: guilty at birth. Feminists reinvented the Bible by repeating the very paradigm they claim to dismantle—and this is precisely where feminism’s despotism rears its head most powerfully.

Look slightly askance at the celebrated practice of “consciousness-raising”—later amplified and monetised by pop culture, political parties, and the media platforming feminist leaders or icons—and feminist politics begins to resemble a hybrid of proselytising and gaslighting. It didn’t merely offer critique; it installed an ideology and a new set of sanctioned desires. The Patriarchy was cast not only as an external structure of oppression, but as an internal contaminant of “misbehaving” women as well. What Betty Friedan diagnosed as the “feminine mystique,” bolstered by Simone de Beauvoir’s “second sex” syndrome, needed to be expunged from the female psyche. The claim was not just that society oppressed women, but that women mistook what The Patriarchy wanted from them as their own desires.

This raises two inconvenient questions: if domestic life under The Patriarchy was so unrelentingly dreary, tyrannical, and life threatening, why did women’s consciousness need to be “raised” about it at all? And second, how is this not manipulation? These questions will be addressed at the close after a more thorough political psychoanalysis of feminism.

Feminist Jouissance and the Politics of Enjoyment

Ideologies include the fantasies that structure the field of desire by configuring what to desire and how, through the distribution of enjoyment. Fantasy is not an escape from reality but the structure through which we relate to it. It offers us a position, a role, a sense of meaning. To be trapped in the fantasy of The Patriarchy, for example, is to be inserted into the feminist libidinal economy—to have one’s desire scripted and one’s enjoyment formatted according to its narrative of lack, oppression, and redemption. Hence Lacan’s aphorism: Ne pas céder sur son désir—Do not give way on your desire.

Enjoyment and pleasure are not the same. Pleasure has a measure; enjoyment does not. When one is thirsty and drinks until the thirst subsides, they’ve been temporarily liberated from—or relieved of—thirst. That is pleasure. But if the person relishes complaining about being thirsty, about having been thirsty, and about the drink being too cold or too warm, we are in the domain of jouissance—Jacques Lacan’s term for excessive or transgressive enjoyment. Some of us—perhaps most of us—enjoy the act of complaining itself, independent of what we are specifically complaining about. There is no clean English equivalent, so enjoyment must suffice. Jouissance is surplus gratification, a kind of glee that is indifferent to the well-being of the individual, the group, or the public. And yet, we typically remain unaware of our economy of enjoyment. It is precisely this repressed or disavowed structure of jouissance—this surplus, unconscious enjoyment—that makes it such a potent force to tap and channel.

Feminism, like all ideologies, inaugurates a fantasy framework that scripts how women ought to understand their situation. It provides what Althusser called an “imaginary relationship to real conditions.” The “liberated woman” ideal is a narrative about what women should desire, how they should enjoy, and whom—and what—they should blame for their lack of fulfilment. Women who do not agree or aspire to this narrative are dismissed as “pick me’s” or diagnosed with “internalised patriarchy.” For noncompliant women, feminism oppresses by inserting these women into a fantasy that is not their own. It offers a script of freedom that demands the renunciation of unapproved desires—and punishes those who refuse to play along in rules to which they not only never agreed, but were never consulted in their drafting.

The public reaction to the “What is a woman?” UK Supreme Court ruling offers an illustration of the difference between pleasure and enjoyment and how the two operate in feminist discourse.5 When For Women Scotland and their allies heard the Court’s unanimous decision—that the legal definition of “woman” is “adult human female”—the pressure of not knowing, and the fear that the Court might conflate sex with “gender identity,” dissolved. Regardless of one’s politics, definitional clarity produces relief. The tension dissipates. That’s pleasure.

Now for the jouissance. Both sides, TRAs (trans rights activists) and TERFs (trans-exclusionary radical feminists), exhibited enjoyment—not in the ruling, but in its aftermath. The TRAs reacted to the decision as if it were a pogrom. TERFs, in turn, enjoyed the outrage of the TRAs—they relished framing the reaction as a “patriarchal tantrum.” What screams “rule of the Father” more than men pretending to be women pitching a fit about “cis oppression”?

TRA and TERF enjoyment fuel each other. The vocation of the drive is the compulsion to repeat whatever generates jouissance. Unconsciously, neither side wants this battle to end. There is every indication that this struggle has become an affective structure, a libidinal loop. And when the sex/gender war finally wanes, it will be marked by an uncanny mix of relief and grief: relief that the issue is resolved; grief over the loss of enjoyment it provided.

Enjoyment is political. Todd McGowan notes that while struggles take place all the time over what form of enjoyment will predominate, no politician, activist, or theorist wants to confront the politics of enjoyment. Conservative and reactionary politics enjoy excluding by positing enemies, and their witting or unwitting abettors, whose elimination or defeat sustains a fantasy of internal coherence. Emancipatory politics, by contrast, enjoys occupying contradiction, the sites the status quo deems impossible, such as the intelligent housewife or the sexually confident mother. Feminism, by this distinction, is contradictory: it is an ideology of liberation dominated by structures of enjoyment that get off by oppressing feminist non-conforming women and men. It codifies an inflationary list of acceptable and unacceptable actions, words, and desires.

Feminism requires enemies and scapegoats onto which it can project all negativity and contradiction. Around this symbolic figure and its female abettors, this master, phallic signifier organises feminist identity through a shared libidinal economy. That enemy of course, is The Patriarchy, which feminists find wherever they go in search of it: still more male than female CEOs? The Patriarchy. Men pretending to be women? The Patriarchy. Women pretending to be men? The Patriarchy. Trad wives and Only Fans? Also, The Patriarchy.

The contemporary feminist libidinal economy is dominated by obsessive and perverse forms of jouissance. Obsessive feminist jouissance substitutes administration for liberation: it replaces the Law of the Father with a neurotic Big Sister. This is a feminism driven by the fantasy of omnipresent male domination and violence which enjoys locating, documenting, and regulating that menace. Whereas perverse feminist jouissance substitutes moralising and shaming for liberation. It enjoys the exposure and reprimand of deviance. Together, these structures of enjoyment constitute a political form that shifts between conservative and reactionary valences. Herein lies the core contradiction: a movement claiming progressive intent but animated by authoritarian modes of enjoyment. Feminists enjoy control. There is a thin, porous line between liberation and control. Feminism disavows this ambiguity.

This contradiction—between a discourse of liberation and structures of repression—has marked feminism from the beginning. It is not a recent aberration but a persistent feature of what we call “the women’s movement,” though it would be more accurate to speak of it as some women’s movement. From Mary Wollstonecraft’s treatise on women’s rights to the first wave’s respectability politics, from second-wave feminism’s war on housewives to today’s warring sex/gender factions, feminism has consistently defined itself through an authorised ideal of woman—and a disavowal of women who fail to conform, or worse, who challenge its sacred cows and third rails. What follows is a historical overview of the feminism–defiant women dialectic.6

Late 18th Century Age of Enlightenment and Revolutionary Spirit

Mary Wollstonecraft in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) advocates for women’s emancipation through the cultivation of reason and virtue. “I do not wish [women] to have power over men,” she writes, “but over themselves.” She critiques the cultural emphasis on beauty and charm, arguing that such focus traps women in a cycle of self-objectification: “Taught from their infancy that beauty is woman’s sceptre, the mind shapes itself to the body, and, roaming round its gilt cage, only seeks to adorn its prison.” Wollstonecraft’s proposal, in effect, is that if women wish to claim the same political rights as men, they must change and devote themselves to the development of their intellect and moral reasoning. She does not rail against The Patriarchy, which didn’t become the evil Poohbah of feminist discourse until the 1960’s when the “smash the patriarchy” mantra tickled their fancy. Rather, she focused on what women needed to become in order to claim and be recognised as rights-bearing citizens.

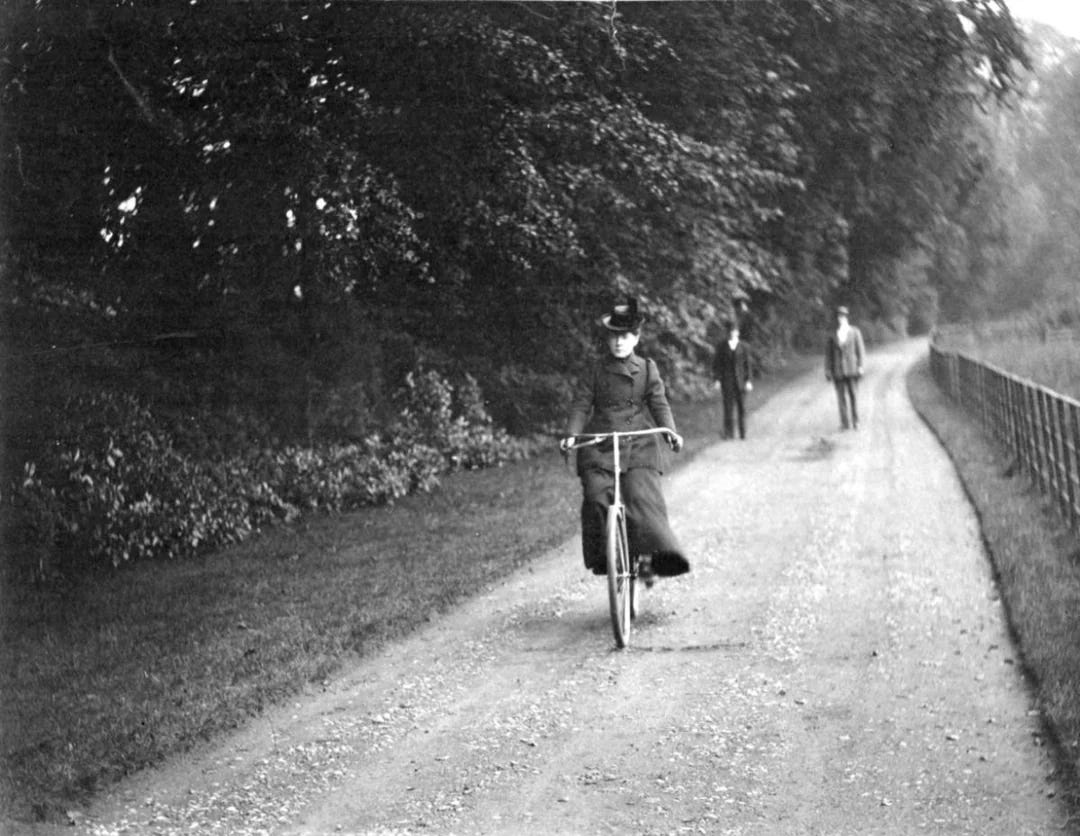

Wollstonecraft’s life (1759–1797), like that of many early feminist figures, undermines the narrative that women were completely oppressed until feminism and the women’s movement freed them from domestic servitude.7 She actively participated in the radical intellectual circles of her time, to include collaborating with figures like Thomas Paine. Wollstonecraft lived and moved with a freedom that feminist histories often make seem impossible for a woman in her era. She had love affairs, travelled to revolutionary France during the Reign of Terror, engaged in politics, and gave birth to a child out of wedlock. Wollstonecraft is rightly remembered as a pioneering Enlightenment intellectual. But her life also reveals a deeper contradiction: that a woman in the 18th century could write, travel, speak, and scandalise—without being forced “back into the kitchen” or erased by patriarchy. The usual feminist narrative would have you believe such autonomy was unthinkable before the movement. Wollstonecraft herself proves otherwise.

19th Century First Wave Women’s Movement: Suffrage and Temperance

The women’s movement in the United States gained momentum after the abolition of slavery, coalescing around two main causes: suffrage and temperance. Unlike Mary Wollstonecraft, who grounded women’s emancipation in rational self-discipline and equality with men, these women emphasised their moral superiority. They saw themselves not as political radicals, but as Christian women, mothers, and moral reformers. The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), under leaders like Frances Willard, argued that women needed the vote not to assert individual rights, but to protect the home from the destructive influence of alcohol and the vices rampant in tavern culture. Willard framed suffrage as a tool of “home protection,” enabling women to extend their nurturing influence into public life. She envisioned women as “citizen-mothers” who would, in her words, “come into government and purify it, into politics and cleanse the Stygian pool.” This was not the language of liberation, but of moral stewardship. These women justified their entrance into politics as an extension of domestic duty, not a rejection of it. Their claim to public authority rested on their natural and divine difference from men, not on equality with them.

Standing in contrast to these temperate, Christian reformers were the women found in the very taverns frequented by their sons, fathers, and husbands: madams, prostitutes, barmaids, singers, dancers, and tavern operators. These “intemperate” women were cast as threats to the moral fabric of society. Yet it was precisely these women who, in their personal lives, embodied the very freedoms that would later be claimed as feminist achievements—economic independence, sexual autonomy, property ownership, and freedom of movement. They ran businesses, navigated public space on their own terms, and formed social worlds outside the domestic sphere. However, because their freedom was tied to impropriety, they have all but been erased from the official story of women’s liberation. These women are not remembered as pioneers of sexual or civil freedom. Their pleasures and livelihoods were, and still are, treated as things to be banned, shamed, or rehabilitated. Ironically, some of the very women condemned by temperance “citizen-mothers,” namely successful madams and brothel owners—used their wealth to fund civic projects which suffragists would later claim as victories of progressive reform. Madams such as Lou Graham in Seattle helped fund the public school system and rescued elite families from financial ruin after the Panic of 1893, while others like Josephine “Chicago Joe” Airey and Anna Wilson financed hospitals and infrastructure projects.8

Although today it is commonly assumed that all women yearned for the vote and were held back solely by The Patriarchy, the historical record tells a different story. Large swathes of women—especially Catholic, working-class, and immigrant women—opposed suffrage throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. Organisations like the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (NAOWS) included women who believed that domestic authority and civic influence could be exercised more effectively through community, church, and family rather than the ballot box. Others simply did not identify with the tone or class position of the suffragette leaders, who were overwhelmingly white, Protestant, and bourgeoises. Suffrage, for them, was not obviously liberating—it threatened to unravel protections and norms they valued. Even Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony admitted that “the greatest obstacle” to the suffrage campaign was not men, but other women.9

20th Century Second Wave Feminism: Parasitic Housewives and Wrong Sex

No more sex arranged on the barter system, with women pretending interest, and men never sure whether they are loved for themselves or for the security few women can get any other way. (Married or not, for sexual reasons or social ones, most women still find it second nature to Uncle-Tom.) No more men who are encouraged to spend a lifetime living with inferiors; with housekeepers, or dependent creatures who are still children. No more domineering wives, emasculating women, and “Jewish mothers,” all of whom are simply human beings with all their normal ambition and drive confined to the home. No more unequal partnerships that eventually doom love and sex… A woman who prefers to be her husband’s housekeeper and/or hostess would receive a percentage of his pay determined by the domestic relations courts… Women with normal work identities will be less likely to attach their whole sense of self to youth and appearance; thus there will be fewer nervous breakdowns when the first wrinkles appear.

—Gloria Steinem, Time (31 August 1970)

The second wave of feminism kicked off in the late 1960s, and since then feminist discourse has evaluated every dimension of women’s public, economic, private, and sexual lives. Feminism—both unwittingly and wittingly—in alliance with capitalism, has helped engineer a cultural shift in which women’s jobs and economic performance have come to take precedence over domesticity and child-rearing as the primary measures of a life worth living. The role of wife and mother has been steadily demoted. Women with children are increasingly told that maternal care is fungible—interchangeable with that of fathers or surrogate caregivers: nannies, babysitters, daycare centres. The housewife who prioritised motherhood, especially those who prioritise being wives and mothers, were regarded as backward and the main impediment to women’s liberation as imagined by feminists. Betty Friedan, the founder of the National Association of Women, describes the 20th century housewife in the feminist classic The Feminine Mystique (1965) as a “parasite” who lives without using adult capabilities or intelligence and lacks a real function when devoting herself to children, husband, and home. She compares them to “male patients with portions of their brain shot away and schizophrenics.”

Feminism’s demotion of motherhood and domesticity dismisses what many women themselves testify to: the gratifications of maternity, which they experience neither as a patriarchal imposition nor as a lamentable biological burden. For them, reducing the aesthetic rituals of homemaking, the intimacy of raising children, and even the marital bed to “unpaid labor” is to diminish their value. These are forms of enjoyment that feminism, since the 1960s, has consistently derided—treating them as signs of false consciousness rather than valid sources of identity. Carolyn Graglia stressed, “I found joy and fulfilment in the very roles feminism declared degrading. I did not need liberation from my home—I needed liberation from feminism’s contempt for it.” She then asked:

Why, one must wonder, are feminists convinced that fulfilling the market demands of strangers is so much worthier an endeavour than attending to the needs of one’s own family? Is it too late to challenge this conviction? A challenge seems necessary because a life that requires the constriction of marital and maternal relationships in favour of materialistic pursuit of career achievement bears a remarkable resemblance to the pornographer’s world of sex without emotion. (1998, p.146 )

Again, feminism demands the repression and disavowal of the wrong kind of female enjoyment—and in the second wave, housewife enjoyment was the most loathed. This contempt is not incidental. In her dialogue with Betty Friedan, Simone de Beauvoir reveals the paternalism embedded within feminist liberation:

No woman should be authorised to stay at home to raise her children... Women should not have that choice, precisely because if there is such a choice, too many women will make that one.10

Here, the mask drops. The goal is not freedom, but compliance. Feminist liberation, stripped of its euphemisms and moral shield, demands the repression of maternal and relational enjoyment. It refuses the possibility that women might find power in interdependence, meaning in care, or pleasure in continuity. To efface or moralise procreation, sexuality, and housewifery is to declare women’s desire invalid—if it fails to mirror the latest incarnation of the feminist ego-ideal.11

On the topic of procreation, Shulamith Firestone, in her 1970 manifesto The Dialectic of Sex, wrote:

Childbearing is a temporary deformation of the body of the individual for the sake of the species’ that hurts and isn’t good for you…It’s like shitting a pumpkin, a friend of mine told me when I inquired about the Great-Experience-You-Are-Missing… Women were the slave class that maintained the species in order to free the other half for the business of the world.

For Firestone, liberation required nothing less than the abolition of the biological family, the end of childbirth, and the use of artificial wombs to free women from what she saw as the tyranny of reproduction. Her rejection of motherhood not only challenged patriarchal power—it disavowed the libidinal and affective structures through which many women actually find meaning.

On the topic of female sexuality, Andrea Dworkin, in Intercourse and Pornography: Men Possessing Women, stated:

There are dirty names for every female part of her body and for every way of touching her... Fucking her is the dirtiest, though it may not be as dirty as she herself is… Being female in this world means having been robbed of the potential for human choice by men who love to hate us.

Yikes! Both women held the female body in contempt: Firestone, for its reproductive function; Dworkin, for its heterosexual vulnerability. Feminists today might call this internalised misogyny, but it reads more plainly as misogyny or, in the parlance of our times, gender dysphoria. Both died child-free and isolated from a movement that had taken a very neoliberal turn. Firestone died alone, and it reportedly took days before anyone noticed and found her body. Cautionary tales or role models for young women? I will leave it to the reader to decide.

Second-wave feminism—despite its revolutionary branding—reproduced a secular Puritanism, this time, ironically, riding the coattails of 1960s sexual revolution. No one has diagnosed this more savagely than Camille Paglia (a sex-positive, libertarian feminist) who pushed back against this “reactionary phase of hysterical moralism and prudery.” In her view, the movement’s leading figures were not bold explorers of female sexuality, but anxious schoolmarms determined to police desire, pathologise eroticism, and blame men for women’s ambivalence about their own sexual power. She defended both the erotic and aesthetics of sexuality. She described Dworkin’s texts as “raging undifferentiated orality,” and “buckets of chicken soup spiked with spite.” For Paglia, this feminism wasn’t radical but reactionary—a fear-driven rejection of the very energies that make life and art stimulating. Beauty, seduction, exhibition—these were not about male domination, far from it. They are part of sexual repertoire, sexual persona to be enjoyed not rebuked.

Despite its rhetoric of freedom, second-wave feminism repressed the very libidinal energies it claimed to free. Its anti-beauty, anti-man, and anti-erotic posture, Paglia argued, amounted to WASP moral reformism in feminist drag. Under the guise of liberation, it carried out a perversion of the sexual. This feminism, according to Paglia, catastrophically misreads sexuality. It wants sex to be clean, safe, egalitarian, and therapeutic. But nature is none of these things. It operates beneath language, beyond reason, and certainly outside the sterilising categories of “enthusiastic consent” and “harm reduction.” What she refers to as academic, professional feminism like that of the National Woman’s Association, harbours a Pollyanna fantasy of Eros, while repressing Thanatos altogether. It dreams of a pain-free, risk-free utopia, achievable only through the despotic regulation of sexual life. As Paglia acidly notes, “The only way to make sex safe is to make it boring” by removing the thrill factor from our mating rituals and sexual personas. And this, for Paglia, is the supreme irony: in trying to protect women from the chaos of sex, feminism infantilises by casting them not as subjects of desire, but as perpetual victims. It doesn’t teach women to master their passions, it teaches them to repress them. It replaces sexual ethics with institutional management, turning the bedroom into a courtroom and pleasure into paperwork. In doing so, it robs women of the power to explore and own their sexual force. It is, at root, de-sexing, thus an insidious form of disempowerment that would likely make the most despotic of patriarchs balk.

21st Century Third Wave Idioms of Feminist Desire & Enjoyments

Don’t go along with The Patriarchy fairy tale? You’re a Men’s Rights Activist! Don’t want to work outside the home? You’re a regressive trad wife! Refuse to affirm gender ideology? You’re a TERF! Refuse to condemn gender ideology? You’re a Transmaid.12

There’s political lesbianism, the fantasy of female separatism—as if women who literally separate themselves from the “man’s world” could survive 48 hours without the built environment overwhelmingly produced and maintained by men. Then again, this isn’t about material reality or the division of labour. It’s about by enjoyment. They lament “toxic masculinity” to the point of even branding toddlers, with a feminist Mark of Cain—all carriers of some patriarchy gene. And women who don’t fall in line are cast as traitors: penis panders, ball palmers.

Say you do not ban your teenage son from listening to Andrew Tate (a fool’s errand by the way), but instead ask him what he finds appealing about the Tate brothers. Big Sister will tell you you are being a bad mother, a “rape-culture”-enabler, a handmaiden of patriarchy. Feminism, in its abusive form, isn’t satisfied with protecting women. It wants to control households, dictate affect, and pre-empt the sexual imagination of teenage boys. Again, what strange liberation is this?

I know feminists who are afraid to say they like Eminem lest they be castigated by Big Sister. Tweet that you had a blast watching Grease with your teenage daughter, and some killjoy will pop up whining about “Sandy changing herself for Danny” and “the male gaze,” while totally disavowing that Danny also changes for her. Let alone acknowledging the “power” Sandy was “supplying” that gave Danny “chills, multiplying” and had him dropping to his knees and following her about like a lovesick puppy? God/dess forbid we enjoy sexuality and mating rituals instead of the latest consent frameworks.

What, exactly, in this feminism appeals to mothers—the women who actually reproduce the species? University and online feminism now elevate three prototypes as avatars of “women’s liberation”: the frigid Big Sister bureaucrat type obsessed with language policing, ideological purity, and micromanaging sexual politics; the pro-porn, pro-prostitution, anti-family libertine type who casts commitment and responsibility as patriarchal traps; and the footloose, “child-free” urban professional who treats parenthood as a cage she cleverly escaped while framing consumption and hyper individualism as freedom.

If you observe closely, you’ll notice the obsessive and perverse enjoyment structuring their discourse and mannerisms. You’ll see the ritualism in their language policing, the constantly shifting taxonomies of who “womans” acceptably, and the compulsive moralising therein. What presents as political conviction is, in practice, a punitive and exclusionary libidinal economy driven by obsessive and perverse forms of feminist jouissance.

This libidinal economy alienates many women—especially mothers and mothers of sons—who were drawn to feminism to advocate for women’s and girls’ sex-based needs and rights. Increasingly, dissent retreats into private, encrypted, or pseudonymous digital spaces—hidden “cells” where women share concerns without risking a public struggle session or being accused of “hurting the movement.” Meanwhile, the public face of feminism, dominated by Professional-Managerial Class (PMC) women, insists there is no dissent at all amongst “real feminists”.

Smash the Sexiarchy!

I need to let all these ho’s know that none of their ni**as is safe.—Cardi B, “Bodak Yellow”

Cardi at the tip-top, bitch, kiss the ring and kick rocks, sis.—Cardi B, “Money”

Feminism rarely celebrates figures like the femme fatale, sex symbols or pop icons as avatars of feminine power or sexual sovereignty. Instead, it tends to dismiss them—revealing not political principle but libidinal envy and disavowal. The rejection of overtly sexually confident women sustains a moral project that alienates women from any form of femaleness that exceeds the feminist script.

Cardi B ruffles both femcel13 and incel feathers precisely because her music unapologetically maps the female hierarchy and sexual economy: where desirability is power and mating is a market. She doesn’t merely describe this system; she thrives in it, flaunts it, and capitalises on it. That’s what makes her so triggering. For incels, she’s the unattainable object. For femcels, she’s the unachievable ideal—someone they can neither be nor compete with. Perhaps when it comes to sexuality what many feminists call The Patriarchy is actually the sexiarchy—the cruel logic of the mating market, structured by both natural hierarchies and cultural beauty norms.

Trial by Media: Enjoy Allegations!

Feminists love a 21st-century witch hunt—so long as the target is a man who rubs them the wrong way. Say that “innocent until proven guilty” should apply in civil society as well as in court, and see how fast you’re labelled a “rape apologist.” Point out that media trials and clickbait headlines manufacture public opinion—and that due process is being replaced by trial-by-Twitter—and you’ll be branded a handmaiden of The Patriarchy. Why? Because in the feminist libidinal economy, due process is a buzzkill. The point isn’t truth—it’s jouissance. The thrill of accusation. The high of outrage. The glow of solidarity through shaming. You need not join in, but spoil the ritual and you’ll catch hell.

What matters is not what happened, but what can be hash-tagged. In the logic of virality, trending equals truth, and virality equals verification. Hashtags become liturgy: #BelieveAllWomen, #TimesUp. The accuser ceases to be a subject making a claim; she becomes a sacred vessel of collective female trauma. To doubt her is blasphemy. To request evidence is to re-traumatise. To speak for rights of the accused is to side with The Patriarchy.

This does nothing to help real victims of sexual violence—those without PR teams, clickbait appeal, or hashtag campaigns. “Believe women” began as a pushback against authorities too quick to dismiss allegations. But it quickly metastasised into a secular commandment. MeToo feminism didn’t so much expose “rape culture” as brand it, gamify it, and weaponise it. It replaced due process with trial-by-social media. No charges? Doesn’t matter. Think Louis C.K. Found not guilty? Still guilty in the court of public opinion. Remember Kevin Spacey? Turns out the man was the victim, like with Johnny Depp? Doesn’t matter. Real feminists are still die-hard Team Heard.

In this moral economy, the accusation becomes myth while the accused becomes a sacrifice. Moreover, feminists get to enjoy the trial, the ritual, the catharsis—again and again. Trump once said, “When you’re a star, they let you grab them by the pussy.” Here’s the feminist remix: When you’re a feminist, you can accuse anyone, destroy reputations, rewrite history—and call it justice. Why? Because every injustice, real or imagined, ever visited upon a woman becomes their conterminous cudgel and shield.

The way feminists enjoy The Patriarchy is, in this sense, conservative at best and reactionary at worst. The fantasy of The Patriarchy provides the certainties, grievances, and moral elevation that obscure the contradictions of modern sexual life. In 1970, Hannah Arendt gave us a framework of power that exemplifies how anachronistic feminism’s central antagonist is:

The rule of man over man—of the one or the few in monarchy and oligarchy, of the best or the many in aristocracy and democracy—has now been replaced by something more formidable: bureaucracy, the rule of Nobody. In this regime, no men, neither the few nor the many, can be held responsible… Tyranny, understood as government unaccountable to its subjects, finds its purest form in rule by Nobody. (16)

Feminism, like the Woman Question that birthed it, is a symptom of modernity’s rupture of tradition. The Patriarchy has become a fetish—an ideological decoy that allows feminists to repress, disavow or foreclose the truth: there are no men—neither the One nor the Many—who can be meaningfully held responsible for the state of womanhood. Certainly not as a coherent class in a world increasingly governed by market forces, bureaucracy, algorithms, and legal fictions.

Pervertgate & Feminist Blackshirts

Feminism disciplines to liberate and polices to protect. Has the line between empowering and controlling, between safety and surveillance, ever been thinner? Feminism conscripts women into their crusades irrespective of consent and then the vanguard acts slighted when women push back or fail to follow their lead. And Lilith help you if you prod the sacred cow—the sublime object of feminist desire: The Patriarchy™. When one pokes this fantasy—and asks what feminists want and how they enjoy—paranoia erupts. They enjoy their symptoms, the libidinal stakes of sexual politics.

While feminism generates volumes of discourse about oppression sourced to The Patriarchy—it resists confronting its own oppressive manoeuvres and ethos. It resists facing the enjoyment it derives from oppressing in the name of liberating or protecting. Case in point: the histrionic reactions to my original thesis that The Patriarchy is not a material structure, but a fantasy, one to which feminists are libidinally attached because of what their position within that fantasy affords them. One male ally of a coterie of feminists is compiling and posting a social media dossier against me and my platformers, presumably for submission to some Feminist Bureau of Investigation’s Special Heresy Unit. The crime? An unauthorised political psychoanalysis of feminism. Ironically, “Feminists to the Patriarchy: We Hate You, Don’t Stop!” was originally meant to be a one-off somewhat tongue in cheek provocation inspired by an illuminating back-and-forth on X with some gender studies professor who bristled over my response that patriarchy had become a chaotic and analytically useless concept.14 But the out-of-proportion responses indicated that I had hit quite the libidinal nerve. So, of course, I persisted.

The bourgeoisie, wherever it has got the upper hand, has put an end to all feudal, patriarchal, idyllic relations.

—Marx & Engels, The Communist Manifesto (1848)

“Feminist’s Fetishistic Disavowal” wondered why second wave feminism gave itself the task of “smashing the patriarchy” when, in historical and material terms, capitalism had already dispatched it. It went deeper into how The Patriarchy, this undead Father, structures feminist desire. “Enjoy Patriarchy!” took it further: what if feminist subjectivity today is not primarily concerned with combatting misogyny or safeguarding women’s rights—but with the jouissance that the surveillance, exposure, and condemnation of bad men and disobedient women the fantasy of The Patriarchy affords.

The use of established categories and concepts from political psychoanalysis—perverse, hysteric, and obsessive relations to ideological fantasy, desire and jouissance—brought accusations of “bullying,” and claims that I was a “vile denigrator” of beatified feminists—or, more bizarrely, that “women’s rights aren’t yours to give away!” Again, methinks the Feminists doth protest too much. Regarding Pervertgate, both Lacan and Žižek refer to Hegel as a “sublime hysteric.” There are also two documentaries, directed by Sophie Fiennes and featuring Žižek, titled The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema (2006) and The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology (2012). And no, this mode of analysis is not some misogynistic Trojan horse. Feminist legal scholar Jeanne Lorraine Schroeder’s The Four Lacanian Discourses: Or Turning Law Inside Out and feminist Lacanian Joan Copjec’s Read My Desire—which, incidentally, includes a philosophically devastating takedown of Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble—both work explicitly with psychoanalytic concepts such as the “hysterical subject,” the “hystericised position,” and the “perverse, fetishistic structure” of enjoyment.

So, to those scandalised by this vocabulary—that’s a you problem. This is structural psychoanalysis applied to collective discourse. It’s not personal; it’s about how subjects are bound to ideological formations through fantasies, defence mechanisms, and structures of enjoyment. We all relate to discourse through some mix of repression and disavowal. Everyone is a bit neurotic and perverse—some more than others, and some pathologically so.

One does wonder by what epistemic or political authority do these feminists presume to police which analytic frameworks are admissible when feminism itself is the object under examination? What’s the message being delivered here? That feminism is beyond critique, a closed shop? Are feminists a sacred caste? When critique is met with caricature, misrepresentation, smearing, and block-button tantrums, it doesn’t prove the critique wrong, it indicates a feminism that cannot withstand scrutiny. Or, is feminism revitalising The Patriarchy by becoming it?

Fortunately, I’m not under the jurisdiction of their kangaroo courts, nor intimidated by the feminist blackshirts and their farcical inquisitions. Quite the opposite. Punishing dissent and enjoying control is a perverse form of liberation. If jouissance is surplus enjoyment that operates unconsciously, then the intensity of the response is diagnostic. This is not about harm. It is about their enjoying being offended, and the opportunity to lash out that offence affords.

Feminist Drive to “Save the Phenomena”

The Patriarchy is not just an outdated term. It is an objective fiction: a fantasmatic construction that structures feminist discourse—not despite its lack of empirical coherence, but because of it. As theorised in Lacanian and Marxist traditions, objective fictions are not mere lies we believe out of ignorance. They are ideological formations that persist precisely because they organise desire, structure enjoyment, and stabilise contradiction within a social order. These are the fictions reality itself requires in order to function. To borrow from Žižek: these are not fictions we naively believe, but fictions we disavow while acting as if we believe. Feminists know very well The Patriarchy doesn’t exist like it used to but all the same…

That’s the logic of feminist disavowal. They know the Father is dead. But to maintain identity, mission, and moral legitimacy, they must act as if He still rules. The Patriarchy has become what Marx called a “real abstraction”—no longer a sociological structure, but a fantasy that exerts real effects. It organises policy, disciplines language, justifies repression, and directs moral-political aggression.

Feminists are not “wrong” about everything. As with conspiracy theorists who sometimes identify genuine grievances—economic inequality, political corruption—feminists do flag real issues. But The Patriarchy, as a totalising explanation, functions the same way the Deep State or the Elders of Zion do: it explains everything, which is to say, it explains nothing. Its power lies in its vagueness. It shifts, multiplies, and updates with each new offence. And like all good conspiracy theories, it is unfalsifiable. In other words: heads, it’s patriarchy; tails, it’s patriarchy too. This isn’t just a bad concept; it’s a libidinal structure. A fantasy feminists enjoy. It delivers moral high ground, a villain to oppose, and a justification for surveillance and discipline. But most of all, it allows them to enjoy: to enjoy complaining, to enjoy punishing, to enjoy being oppressed and superior, all at the same time.

Feminism clings to the fantasy of The Patriarchy not merely as political adversary, but as fetish-object—a sacred referent that legitimates its identity and authority. Faced with the collapse of grand narratives and stable subject positions, feminism doubles down on a single totalising signifier: The Patriarchy. This isn’t traditional conservatism, but what Wendy Brown calls “reactionary foundationalism”: the desperate preservation of a decontextualised fragment of a once-coherent worldview (here, male domination) as an untouchable anchor of meaning.

Just as traditionalists cling to “the family” or “Western civilisation,” feminism clings to The Patriarchy as its organising fiction. And like all reactionary foundations, it resists critique. It becomes scripture—beyond hermeneutics, beyond politics. Feminists know capitalist modernity has de-centred the Father. But they act as if he rules from everywhere. This is not ignorance—it is fetishistic disavowal, a libidinal investment in patriarchal domination as a symbolic guarantee. It shields feminism from the more traumatic truth: the symbolic death of the Father and the collapse of sexual order.

But this foundationalism is not only epistemological—it is libidinal. The Patriarchy functions as a fantasy anchor not because it explains the world, but because it organises feminist enjoyment. It offers a stable enemy around which outrage, identity, and moral superiority can constellate. Its very spectrality—its vague, shifting, shape-shifting nature—facilitates the repetition compulsion: an endless cycle of grievance, exposure, and righteous condemnation that delivers jouissance.

This is the terrain of the death drive, not the pleasure principle. Feminist discourse returns obsessively to The Patriarchy not to destroy it, but to fail to destroy it—again and again—because that failure sustains the very structure of feminist desire. In Lacanian terms, feminism installs The Patriarchy as its object-cause of desire ensuring the feminist subject remains caught in the loop of chasing liberation while unconsciously enjoying controlling and complaining.

Feminists do not disavow the death of the Father because they do not know it happened. They disavow it because they need him undead. He must linger—omnipresent, but never fully present—so the fantasy can recycle. And with it, the moralistic, punitive, and erotic thrill of being forever oppressed, forever resisting, forever right.

In the history of science, “saving the phenomena” refers to the effort to preserve an explanatory model even after it no longer matches reality. Think of Ptolemaic astronomy: as evidence mounted that Earth was not the centre of the universe, epicycles were added to explain certain anomalies. The model wasn’t abandoned—it was made more elaborate. Not to get closer to truth, but to protect the premise.

Feminism’s investment in The Patriarchy is structurally identical. As material realities shift, power becomes more abstract, and sexual norms fragment—feminism doesn’t rethink. It doubles down. It adds more epicycles: toxic masculinity, mansplaining, emotional labour, incels, woke bros, the manosphere. Everything is Patriarchy. Everything proves Patriarchy. The model explains its own failure. It becomes pure ideology. Feminists, like pre-Copernican theologians, are no longer trying to understand the system—they’re trying to save the sublime object: The Patriarchy. The feminist death drive orbits it. So does their double jouissance—as victim and vanquisher.

Tell me: have you ever heard a feminist say, “Turns out we got that one wrong. It wasn’t The Patriarchy.” I didn’t think so.

The Feminist Question: What Is To Be Done?

The State of Israel was not the goal of Zionism. It was just the bat and the ball—the means to their end. The end goal of Zionism was to change the Jewish people. Having a state—and a language and a culture and an army—were just useful tools to facilitate the desired equalization between Jews and gentiles. The Zionists wanted the Jews to change. The medinah was going to help facilitate that change. As the Zionist Yosef Chaim Brenner explains: “In order that our character be changed as much as possible, we need our own environment.” Character change of the Jewish people was the primary objective of Zionism, and the State of Israel was merely going to be the “new environment” that was to bring about the character change in the Jewish people…They do not want to shmad [change] the Jews in order to create a state. They want to create a state in order to shmad the Jews.”

—Rabbi Yaakov Shapiro, The Empty Wagon: Zionism’s Journey from Identity Crisis to Identity Theft (2018)

Feminism’s relationship to women increasingly mirrors Zionism’s relationship to Jews: it claims to speak for us—whether we want it to or not. Like Zionism, feminism cloaks paternalistic entitlement in the language of emancipation. Speak out of turn, and you’re not just mistaken—you’re a traitor. Act out of sync, and you’re accused of internalised misogyny or branded a “handmaiden.” Deviate from the doctrine, and the inquisition begins. Feminists anoint themselves guardians of “women’s liberation,” yet turn punitive the moment real women think or act outside their drawn lines. What kind of liberation is this—one that replaces the fading Father with the neurotic vigilance of a perverse Big Sister? Hard pass.

Feminism has a freedom problem—perhaps a terminal one. It appoints itself the supreme guardian of the category woman, past, present, and future, analogous to the role Zionists claim over the category Jew. Like Zionists, feminists grow punitive and paranoid toward dissenters. Zionists denounce Jews who reject their colonial-imperial Greater Israel project; feminists denounce women who reject the dogma that The Patriarchy exists and is ultimately to blame for every obstacle women face—for every nuisance, injustice, or crime involving a human male.

In this context, The Patriarchy becomes a fantasy-object—an imaginary construct that retroactively restores coherence to a fractured sexual and political order. In Lacanese, we might say The Patriarchy functions as the subject obliged to oppress: the structural villain onto which feminist discourse projects its contradictions, disavowed desires, and surplus-enjoyment. It gives feminism orientation—a cognitive map of the social. In this sense, it exemplifies what Fredric Jameson called the political unconscious: an imaginary, symbolic “resolution” of real social contradictions. The political unconscious doesn’t clarify—it narrates. It lends ideological form to disorienting flux: meritocracy, patriarchy, race, globalism, Islamism. These ideological fantasies share a crucial function in modernity: they externalise the contradictions of liberal, now neoliberal, capitalism.

Since the bourgeois revolutions of the 18th century and the industrial upheavals that followed, one rule has remained operative: anything but class. You can blame a religion, a race, a culture, “toxic masculinity,” or fate itself. You can indulge conspiracy theories about secret cabals. Just don’t point the finger at a society structured around private capital accumulation and the socialisation of risk.

Feminism mistakes the anarchy of modern sexual politics and economic life for a patriarchal conspiracy—and in doing so, it enjoys castigating an imaginary obstacle to women’s freedom. This isn’t just strategic misrecognition; it’s a libidinal structure. The repetition of the gesture—naming, shaming, denouncing—delivers satisfaction precisely through its failure to ever dispatch The Patriarchy. They enjoy beating the dead horse. Psychoanalysis calls this the death drive: the compulsion to repeat whatever delivers jouissance, regardless of cost, logic, or outcome. Notice how feminism keeps rebooting with new stand-ins for the missing Father: Dylan Mulvaney, Jordan Peterson, Andrew Tate, Donald Trump. The casting grows more farcical, but the ritual remains intact. This is the logic of the drive: it doesn’t aim at resolution. It circles. It repeats.

This feminist libidinal economy raises an impossible question—impossible because feminist discourse cannot ask it: has feminism, in practice, degenerated into an identity-politics protection racket? Is the main goal defending women and girls—or defending a particular mode of feminist enjoyment? Can this Big Sister despotism and hashtag-influencer activism—which punishes dissenting women under the banner of “smashing the patriarchy”—be reformed? Or should it be left to wither on the vine?

Feminism wants to control women to control men: some feminist sects instruct women to “think, act and fuck like a man” while others try to rid the mind and body of all sexual desire. For example, temperance campaigns, consciousness-raising that demeans housewifery and reframes motherhood—and thus children—as a burden, and the mantra that gender is a social construct. These all converge around the feminist desire to change women at the level of subjectivity. As Wollstonecraft, Willard, de Beauvoir, Friedan, Steinem, Firestone, and Dworkin each convey in their own idioms, the problem was never really The Patriarchy. The problem is the majority of women enjoying “wrongly”—too many refusing to give way on their desire. Feminism does not seek to shatter traditional roles merely to liberate women. It seeks to hegemonise the entire field of relations between and among the sexes—and sex itself. The aim is not emancipation, but installation: to replace their imaginary Father with an all-too-real Big Sister.

Tara van Dijik is a run away train and this is brilliant! Grab a cuppa, because it is long, but it also ferociously intelligent, challenging, commanding, and thoughtful at a time when thinking often stirs outrage.

Brava!

Imagine writing this insightful piece so that most of our mothers, or sisters who could not afford college, could understand a word of it? Imagine it in the mainstream?

That said, aside from its abstruse language and reliance on theorists who themselves just made things up, as nearly all do, this is fascinating.

One thing I assure you> every time a woman uses the word Patriarchy now, particularly as a catch all for 'my world as a woman', let alone if she bothers to, or can indeed, articulate what is meant by her use of it, every time its used or overused or badly used, another man, another woman center or right of center, thinks, yes, I do hate liberals, and radicals, and feminists. - "Yes, I do like this orange buffoon and his worldview."

Caution is the way forward. Teaching young boys and men the lived experience of women - that is the way to change 'structures' through human minds.

PATRIARCHY has little to no use as a notion. Its use in the West is certainly incredibly ahistorical, and like SJW language and its laughable terms, does more harm than good.