Executive Donkeys and War Powers Reform

The Reaffirmation of the Status Quo and the Prerogative of the Executive

The decision to go to war should be as burdensome as possible. The more impediments to such folly, the better. Such a state of affairs does not characterise the Westminster system of government. It certainly does not apply to Australia, which is all the more troubling given a string of disastrous military interventions led by a slavish, ignoramus complex.

As things stand, the National Security Committee, comprising inner cabinet members including the Prime Minister, determines whether Australia goes to war. It replicates the British monarchical traditions of old, and speaks against, rather than in favour, of a Parliamentary voice.

Attempts to challenge such a convention have been previously made. The Australian Democrats made efforts to that end in 1985, 1988 and 2003, all in vain. The Greens have also made similar efforts, with similar results.

In December 2020, Australian Greens Senator Jordon Steele-John introduced a bill before parliament with the express purpose of curbing executive powers in favour of parliamentary debate. “Australia,” stated Steele-John in his second reading speech on the bill, “is one of the few remaining democracies that can legally deploy its defence forces into conflict zones without recourse to the parliament.”

The Defence Amendment (Parliamentary Approval of Overseas) Bill 2020 would require both the House of Representatives and the Senate to pass a resolution permitting troops to be sent overseas before any planned deployment. That attempt has passed into oblivion.

In 2020, a Roy Morgan poll found that 83% of respondents favoured reforms requiring parliamentary approval prior to any decision to go to war being taken. In 2021, a Digital Edge poll found that 87% of Australians were in agreement with the proposition that “war decisions should be subject to parliamentary approval always or unless there is immediate danger to Australia.”

In March 2021, the Australian Labor Party at its national conference determined that, should it find itself in government, hold a parliamentary inquiry into whether war powers should fall within the purview of parliament or continue to be a matter of the executive arm.

With such momentum, much was expected from the Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade. Its Inquiry into international armed conflict decision making promised a departure from convention. But for anyone familiar with Australian political life, committees and selected parliamentary inquiries are alpha signatures of the static. When it comes to challenging the ancient conventions of executive war making powers, it was expecting much to suppose any change in direction.

On looking at the submissions, this should not have been the case. The inquiry received 111 submissions, with 94 arguing for parliamentary involvement in the war making process. But it became clear in the months leading to the publication of the final report what direction the members were heading.

Foreign Minister Senator Penny Wong, in comments made in Parliament on 9 February, revealed that the inquiry would not derail or obstruct the accepted wisdom of executive war making powers. In her reply to a question posed by Senator Steele-Johns, Wong proved a figure of stale convention. “The executive should account to the parliament for such a decision.” That said, “it is, in our view, important for the security of the country that that remains a power and prerogative of the executive.”

On 31 March 2023, the Committee released its final report. It proved intensely underwhelming. Its members acknowledged Australia’s participation in “a number of wars over its comparatively short history, many of which have been tarnished by controversy.” Despite such a chequered history, the members merely affirmed “that decisions regarding armed conflict including war or warlike operations are fundamentally a prerogative of the Executive.” The role of parliament was deemed important, as was “the value of improving the transparency and accountability of such decision-making and the conduct of operations.” In other words, little would change.

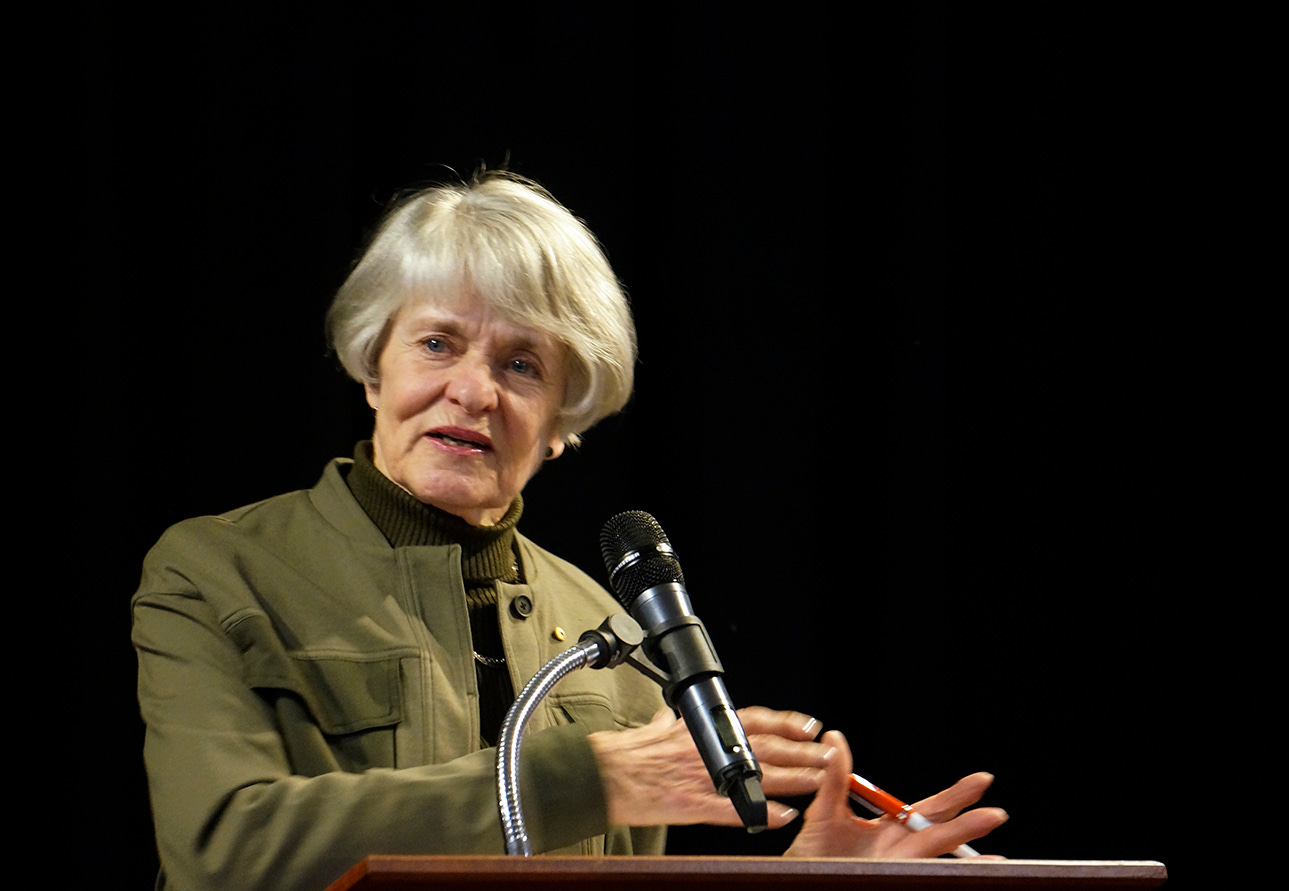

In her response to the report, the President of Australians for War Powers Reform, Alison Broinowski could only express resounding disappointment. “The first recommendation confirms our worst fears—it reaffirms the status quo by insisting that decisions regarding armed conflict are fundamentally up to the PM and the executive.” The implication of this was clear: “MPs and Senators will continue to have no right to vote on a war decision before troops are sent overseas.”

In his scathing account of the leadership overseeing the British Expeditionary Forces in France during the initial stages of the First World War, Alan Clark recalled a famous exchange between two German generals, Erich Ludendorff and Max Hoffmann. “The English,” observed Ludendorff, “fight like lions.” “But,” came the assuring reply from Hoffman, “don’t we know that they are lions led by donkeys.”

The failure of securing war powers reform, at least at this juncture, ensures that the executive donkeys will take Australians into the next needless conflict, fatuously purposed for the US war machine. And it will be done with Parliament gazing at a distance, irrelevant before the slaughter and homicidal impulses of the establishment.