Entering the Resistance Phase of the Surveillance Education Cycle

Finding Ways to Protect Privacy in Schools

In August 2022, two important acts of resistance hinted at a sea change in attitudes toward invasive surveillance technologies. First, New York University’s Brennan Center sued the Department of Homeland Security for violating a Freedom of Information request regarding how the agency utilizes social media to monitor US citizens. Days later, it was announced that the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is suing data brokerage company Kochava for the sale of geolocation information that may violate the privacy of women seeking reproductive health care.

In The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires, technology scholar Tim Wu argues that throughout US history, communication technologies progress in a cycle from a universally accessible medium that brings pandemonium and creativity to a homogenised, sanitized, and pasteurized vehicle that serves industrial interests. At the start of the cycle, the public has a positive view of the medium, believing it will deliver a utopian future, but by the end of the cycle, the public is left with scepticism and scorn toward the medium.

Digital technologies have followed this trajectory, going from an information super highway that promised individual autonomy to a monopoly of platforms that surveil and exploit users. Indeed, responding to the revelations from whistleblowers and investigations that revealed the ways in which tech companies mislead the public, amplify false information on their platforms, engage in inconsistent content moderation practices, knowingly exacerbate mental health issues for users (particularly young girls), ignore privacy concerns when it comes to sharing user data, and prioritize profits over user safety, users have soured the public on tech companies. Only 34% of the public has a positive view of big tech companies.

Surveillance technologies in schools do not seem to foment the same collective ire. Students, families, administrators, and community members are deeply concerned about the inclusion of these invasive technologies in classrooms. Within moments of publishing an article on the connection between surveillance technologies and book burning, we received copious messages from concerned readers with examples of educational surveillance infractions in their communities noting that they feel isolated in their knowledge of surveillance invasion and powerless in how to respond.

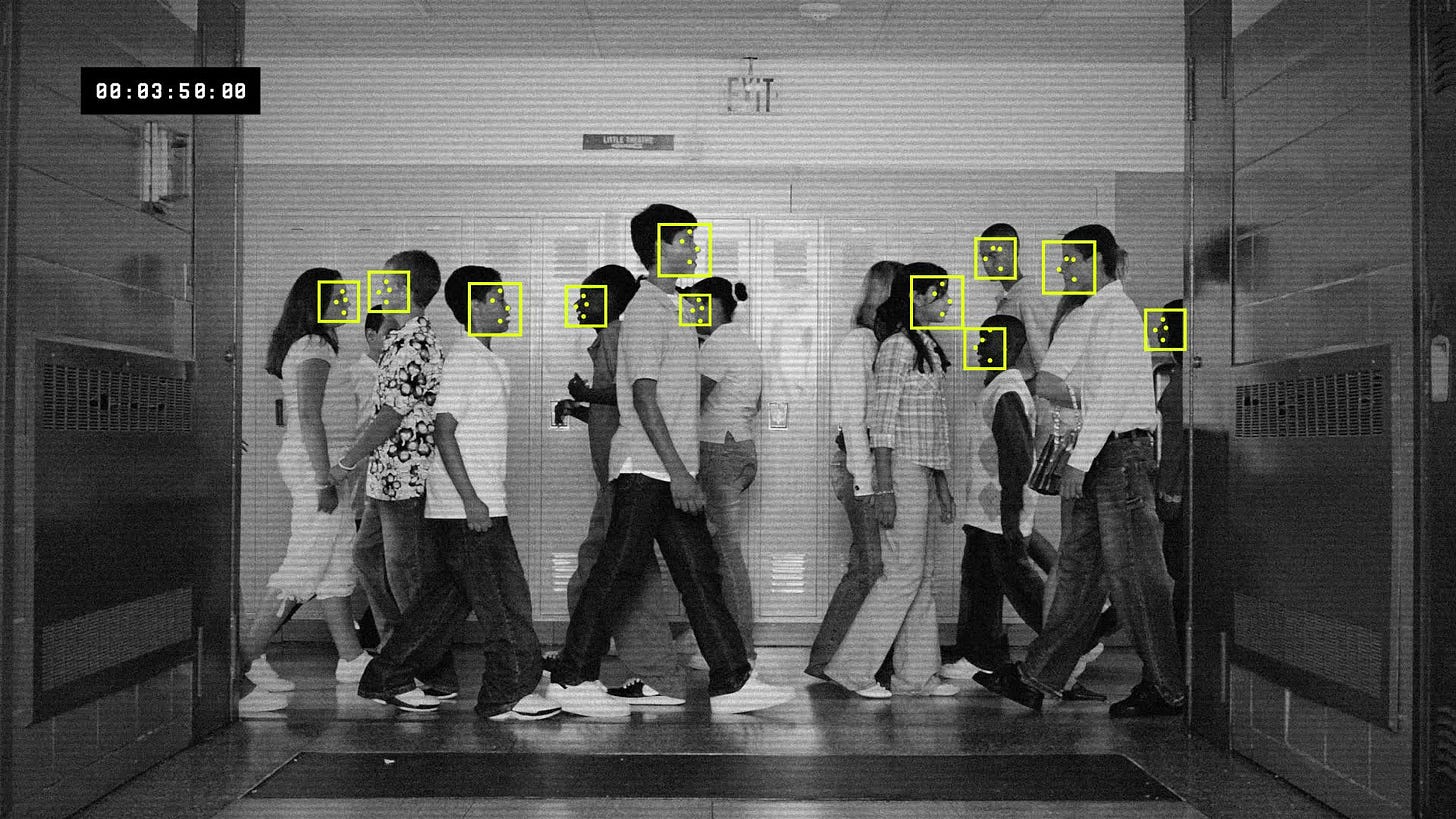

Schools use digital technology such as facial recognition software and school-issued devices to monitor students’ social media use, mental health, mood, and almost every movement on campus. Big tech companies have long tried to enter the classroom, and have found success by offering economic incentives to educators and “free” devices for students such as laptops and Chromebooks. Big tech has exploited loopholes in the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) of 1974 and the Children’s Internet Protection Act (CIPA), by adding and collecting data from monitoring tools to all school-issued devices. Under the auspices of helping schools Gaggle, GoGuardian and Securely offer packages to filter content on school-issued devices.

The data collected from these devices can be sold to third parties such as the US Military and intelligence agencies, both of which are known to receive and share data with big tech. Student data also becomes available through data breaches, which occur frequently—1850 breaches since 2005, or about 108 per year. Data can be used by law enforcement to prosecute students, data brokers and advertisers to predict or modify student behaviour, stalkers to target individuals, and by powerful institutions to disrupt activism.

The shift to online learning during COVID-19 saw privacy advocates voice concerns for teacher and student privacy, but the subsequent response has ramped up student surveillance. For example, a Washington State programme aimed at screening young people for mental health concerns was sharing extremely sensitive information captured from the students with third partners. Unfortunately, most current pushback is largely weak and toothless legislation. This is typified by a Maryland proposed policy that aimed to set boundaries for data collection but left students vulnerable to data breaches.

As a 2019 judgment against Google reveals, there is little incentive to end problematic practices. Even when legislation holds companies financially responsible for compromising user privacy—such as Children’s Online Privacy Protection Rule (COPPA) or California’s Children’s Online Safety Bill—the profits made from collecting and analyzing student data far outweigh the fees paid for the violation.

Some of the student awareness and frustration with digital surveillance in schools has actually thwarted the learning process because they practice resistance in the form of less classroom engagement and self-censorship. In a rare example of resistance, in August 2022, a federal judge ruled that Cleveland State University violated the US Constitution when it allowed instructors to use video and other third-party software to scan a student’s home while taking an exam. The lawsuit was brought about by Aaron Ogletree, a matriculated student, and represents a major win for students and privacy in schools.

It remains to be seen if these are the early stages of the final phase of Wu’s cycle, but these collective efforts represent significant resistance to big tech’s efforts to normalize surveillance and user isolation.