Embracing Ambivalence

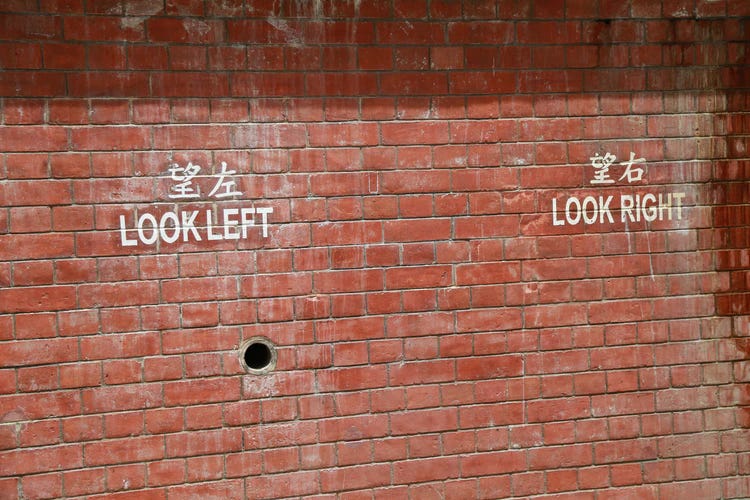

Thinking Beyond “Left” and “Right”

There have been many generations of humanity before this one. Many men and women who lived together and loved each other, sometimes, and had children, or didn’t and worked, or didn’t. These people inherited some wisdom from their elders, and would have had to confront developments in technology in their own lifetime. There would have been problems that they would have had to confront collectively and individually, drawing upon traditional or religious virtues, or invoking the law where necessary.

Major shifts in human history, mapping on to technological transformations, seem to be a paradoxical feature of our human nature—that is to say, we are creatures for whom tool-use is a central part of our being, to the extent that we in turn are transformed by technology, for better or worse. In that sense, then, it does not always make sense to oppose technology to nature, or humanity to the rest of the planet, imagining ourselves either masters or parasites. But to what degree are we unlike our ancestors? Whether we imagine feudalism, with its hierarchies and ties to land and rhythms of the seasons, or our supposedly repressed Victorian forebears, we inevitably imagine that we are superior in some way, more advanced, more ‘modern’.

Yet many of our problems are the same, if not compounded by the technologies adapted to make life easier. We struggle to be virtuous, even if we believe we are beyond religion. We struggle not to act in religious ways, even though we are supposed to understand that life is thoroughly dominated by the scientific worldview. We worry about the same things as our ancestors, feel the same emotions and confront the same kinds of suffering.

What does all this have to do with politics? After modernity, after the sexual revolution, after the internet, where do we find ourselves? How do and can we get on? All of the major universalising projects—Christianity, the Enlightenment, capitalism—have seemingly collapsed, with only the latter clinging on to its exchangeability and systematic commodification while tumbling through crisis after crisis. At the very least, we can say that capitalism does not provide us with any ideals worth preserving; on the contrary, it destroys all values, all tradition, as Marx makes clear.

Neither the “left” nor the “right” appear very strong today, though each blame the other and assume the other has power when it perhaps does not. Conservatism sold out long ago to free market capitalism, thus crumbling its ideological commitment to slow-moving politics and preservationist ethos from under itself. The left, where not a different colour of the free market, has lost a grip on the very people it is supposed to represent—the working-class, the dispossessed, those who would most benefit from redistribution. The “liberal left” has become instead pedantic and judgemental, and neglectful of poorer heartlands. The left has abandoned class, the right, tradition. Neither “side” really exists anymore. This both closes chapters and opens up new possibilities.

The technocracy that confronts us today of either stripe is a hodgepodge of bureaucracy, authoritarianism, incompetence, corruption, and it is bereft of morality. As the pandemic reveals, governments prefer to truck in fear than reason, or are perhaps incapable of explaining to people just like them why measures are being put in place, and why. In the UK, no political party has managed to consistently ask what the effect and consequences of the lockdown will be: there is no real opposition to speak of. Questions about what we value, or why we bother to stay alive, are absent: everything is calculation.

Meanwhile, another “culture war” consumes energy—whether of those mounting it, those suffering it, or those (incorrectly) denying it exists. Various figures, events and debates—Trump, Brexit, sex/gender, BLM, the lockdown, free speech itself—are mobilised as both distractions and pernicious dividers of humanity, creating enmity where there is likely more agreement than imagined.

I might be nostalgic, or misremembering, but I don’t think so, when I say that the “old left” was a defender of free speech, pro-freedom of association and for free expression against a censorious right. The old left had a sense of humour; that it was committed to kindness and forgiveness and equality. It did not seek to divide people, indeed, it spent much of its time pointing out that the ruling class and capitalists benefitted from precisely this tactic. It understood history from a materialist point of view: that is to say, it understood how real men and women were conditioned by their time, but also the power they had to shape it. It did not seek to cover-over history, or to sugar-coat it: rather history’s lessons, as well as its science and art, belong to all of us, and each of us are tied to it irreparably.

The new left does not resemble the old left. A curious combination of sadism, emotionalism and unearned moral superiority appears to dominate many of our institutions, and there seems to be little interest on the part of the righteous in listening to anyone older, or anyone who disagrees. It is a profoundly lazy position, imagining that people who live today somehow know better than everyone who ever came before them how life should be lived, what can be said, and how reality works. The real question is not perhaps where this outraged (largely) youth came from, but rather why institutions are not strong enough to hold onto greater values. When the bottom line is money, controversy starts to look frightening…

I don’t actually believe that most people think, act or feel so simply, though. I think a small number of narcissists have come to dominate political discourse at all levels, and we as a society are unable to recognise these motives for what they are, in part because we want to be sympathetic, and narcissists are excellent at playing on the kindness of strangers. This is why it is imperative to hold onto reality—think of the word “based”—whatever your politics are. Why it is important to be honest, and not to avoid complexity when difficult political problems, and disagreements, present themselves. How does the world seem to you? What do you really think? How would you like the world to work? How can we arrange things in the best way possible for everyone?

We are all complex creatures, driven in part by desire, in part by reason. We are also not so unlike those we seemingly oppose, and it is our want of similar things that often drives our animosity towards one another. How can we embrace our ambivalence, about ourselves, about others, and make it not in to the nihilistic dead-end of our politics, but rather the starting point for thinking of a new politics, beyond “left” and “right”?

After years of hurling inaccurate insults, the time has come to talk: what shall we speak about?