Politics and facts are not necessarily good dinner companions. Both often stray from the same table, taking up with other, more suitable company. The Australian opposition leader, Peter Dutton, has never been discomforted by facts, preferring the chimera-like qualities demagoguery offers. His vision for Australia is admirably simple and simplistic.

In foreign policy, he supports US interventions in any theatre of the globe without question. Ditto such allies as Israel. To the distant north, the evil Yellow Horde is abominated. Domestically, matters are similarly one dimensional. Irregular boat arrivals are to be repelled with necessary cruelty. And then there is a near pathological hatred of renewable energy.

Needing to find some electoral distraction to improve the Liberal-National coalition’s chances of returning to office, Dutton has literally identified a nuclear option. Certainly, it is mischievous, throwing those wishing to invest in the problematic Australian energy market into a state of confusion. The business of renewables, as with any investment, is bound to also be shaken.

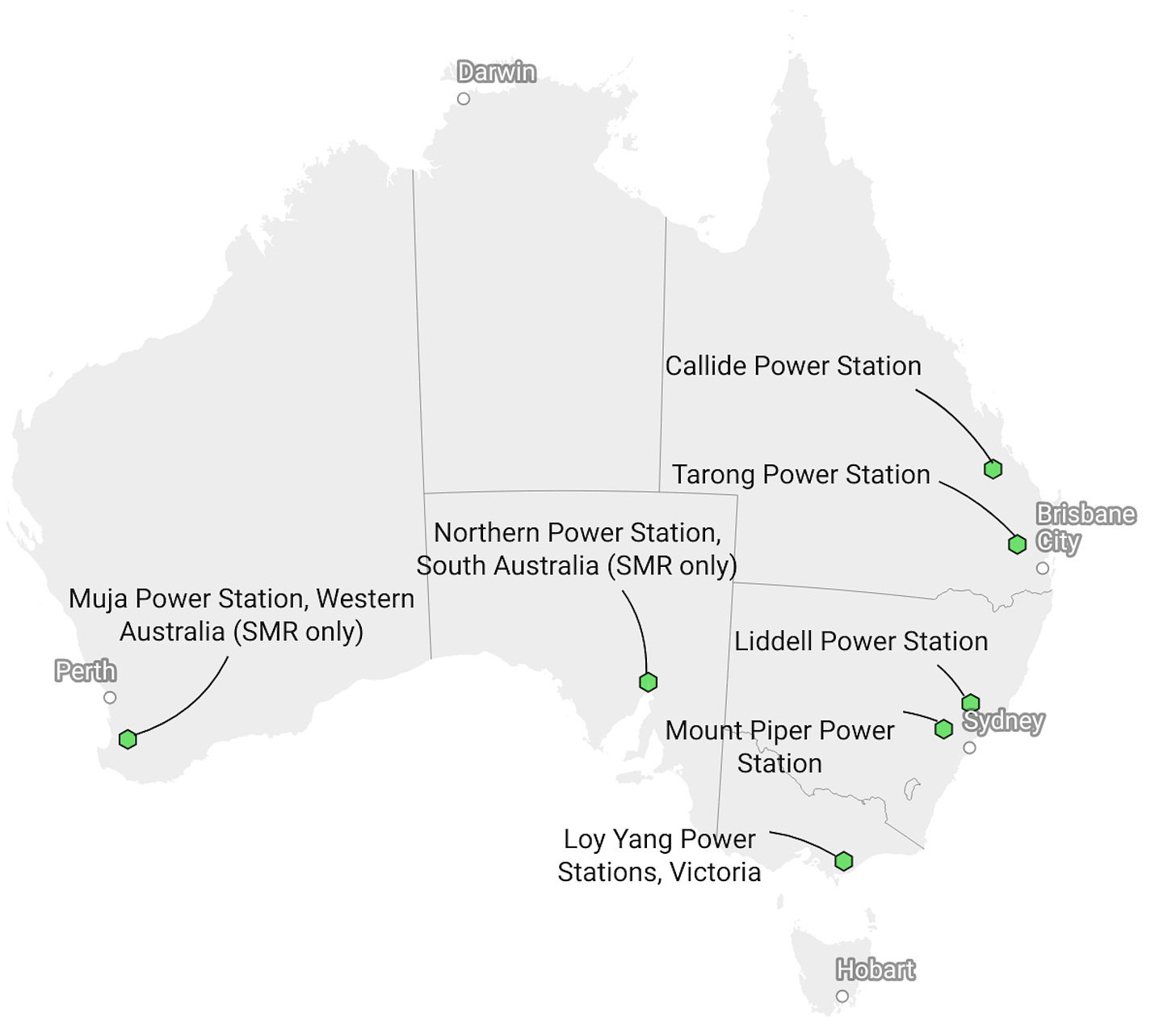

Last month, Dutton finally released some details of his nuclear vision. Seven nuclear projects are envisaged, using sites with currently working or shuttered coal fired power stations. These will be plants up to 1.4 gigawatts (GW) to be located at Loy Yang in Victoria, Liddell in NSW’s Hunter Valley and Mt. Piper near Lithgow, Tarong and Callide in Queensland. Small modular reactors (SMR) are planned for Port Augusta in South Australia and Muja near Collie in Western Australia.

The SMR gambit is particularly quixotic, given that they have yet to come to viable fruition. Besides, the entire reactor venture already faces glaring legal impediments, as nuclear power is prohibited by Commonwealth and state laws. (The ban on nuclear energy was, with sweet irony, legislated by the Howard Coalition government a quarter of a century ago.)

Already, the handicaps on the proposal are thick and onerous. Ian Lowe of Griffith University witheringly describes the proposal as “legally impossible, technically improbable, economically irrational and environmentally irresponsible.”

The greatest of all handicaps is the fact that Australian governments, despite tentatively flirting with the prospect of a civilian nuclear sector at points, have never convinced the citizenry about the merits of such power. The continuous failure of the Commonwealth to even identify a long-standing site for low-level radioactive waste for the country’s modest nuclear industry is a point in fact.

Aspects of the proposed program also go distinctly against the supposedly free market individualism so treasured by those on Dutton’s side of politics. If nuclear power were to become the fundamental means to decarbonise the Australian economy by 2050, it would entail crushing levels of debt and heavy government stewardship.

By its very nature, the Commonwealth would have to take the reins of this venture, given that private investors will have no bar of it. Tom Dusevic, writing in the otherwise pro-Dutton outlet The Australian, put it thus: “There is no other way because private capital won’t go anywhere near this risky energy play, with huge upfront costs, very long lead times and the madness that has pervaded our energy transition to meet international obligations.”

The extent of government involvement and ownership of the proposed nuclear infrastructure made The Age and Sydney Morning Herald search for a precedent. It seemed to have an element of “Soviet economics” to it, directly at odds with the Liberal Party’s own professed philosophy of “lean government that minimises interference in our daily lives; and maximises individual and private sector initiative.”

It would also further add to the already monstrous AUKUS obligations Australia has signed up to with the United States and United Kingdom, a sovereignty shredding exercise involving the transfer and construction of nuclear-powered submarines to Canberra costing upwards and above A$368 billion. The Smart Energy Council has been good enough to offer its own estimate: the seven nuclear plants and reactors would cost somewhere in the order of A$600 billion, securing a mere 3.7% of Australia’s energy share by 2050.

While draining the treasury of funds, the nuclear-in-Duttonland experiment would do little to alleviate energy costs. The CSIRO, Australia’s national science agency, along with the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO), have concluded that nuclear power in Australia would not be prudent in terms of cost relative to other sources of power. The obstacles noted in their 2023-4 report are impressively forbidding.

Australia, for instance, lacks existing nuclear power projects. “Therefore, although it is true that all technologies have extensive pre-construction development times, nuclear is unique in that it has an empty development pipeline in Australia.” Throw in the layers of legal, safety and security steps, any pioneering nuclear plant in Australia would be “significantly delayed,” rendering nuclear power’s role in achieving net zero emissions by 2050 a nonsense.

The Dutton plan is scratched of all empirical shape. Estimates are absent. Numbers, absent. Capacity, absent. Figures, if supplied, will be done immediately prior to the next election, or while in government. Such moves teeter on the edge of herculean stupidity and foolhardiness, at least in Australian conditions. The exercise is also, quite rightly, being seen as an attempt to stealthily retain coal fired stations while starving continued investment to the renewable sector.

Dutton’s junior partner, the Nationals, have also shown much candour on where they stand on renewable energy projects. Party leader David Littleproud nailed his colours to the mast on that subject early last year. By August 2023, he was explicitly calling for a “pause” to the roll out of wind and solar and transmission links, calling the Albanese government’s pursuit of their 82% renewables target a “reckless” one. His implicit suggestion: wait for the release of the nuclear genie.

The Coalition opposition’s nuclear tease continues the tendency in Australia to soil climate policy with the sods of cultural conflict. On any matter, Dutton would be happy to become a flat earther were there any votes in it. The problem here is that his proposal might, on some level, be disruptively attractive—in so far as the voters are concerned. With Labor dithering in office with the smallest of majorities, any disruption may be one too many.