In politics, the once in century tag is virtually unheard of. Miracles can take place in a matter of weeks if not months, but there is always an allotment of certainty that some things will never change, affixed in reliably sturdy stone. In the context of the Australian federal seat of Aston, located in Melbourne’s eastern suburbs, that tag rose with menace from the history books and chronicles, revealing that most unusual of phenomena: a swing of votes to the government of the day.

Usually, little can be made about by-elections. The electors can be a cranky lot. Given that Australia’s federal elections are a compulsory affair, being forced to vote outside standard national or state polls can make them even crankier. It’s an inconvenience, an interruption to the weekend routine, and made all the more biting by the fine that needs to be paid in the event of not turning up. In Australia, the vote is more rite and obligation than right and liberty.

Sturdy, dramatic swings against incumbents have assumed the properties of natural law and holy writ. Rarely does it go the other way. On 1 April, it not only went the other way, but dramatically so: some 6.5 percent in favour of the Albanese government and its Labor candidate, Mary Doyle, and away from the opposition Liberal Party and their candidate, Roshena Campbell. (Neither, it should be said, were of Aston, but Doyle, as commentators remarked, had lived in the nearby environs.)

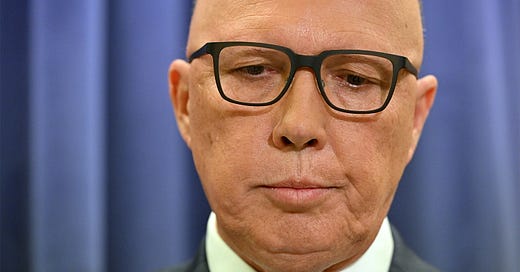

It is with little surprise that the event stirred psephologists, tickled the pundit classes and moved a goodly number of social mediacrats to suffer kaleidoscopic fits of analysis. It certainly left much room for raking through the credentials, and capabilities, of that most unappealing, unattractive of leaders, Peter Dutton.

First, the leader’s slant impressions, strained as they might be. It was, he explained, “a tough night for the Liberal Party and our family here in Victoria where … we have been out of government 20 of the past 24 years.” He conceded that much work lay “ahead of us to listen to the messages sent to us today from the people of Aston but listen to them, we will.”

The next day, on the ABC’s Insiders program, Dutton focused his attention on the peculiarities of Victoria: that state’s voters, not his leadership, was the problem. “Obviously, the difficulties for us in Victoria haven’t been germinated in Aston over the course of the last five weeks.”

He should know: for years now, Dutton’s own electoral appeal has been considered, even within his own party, poisonous in the southern state. As Home Affairs Minister in 2018, Dutton famously remarked on Sydney’s 2GB Radio that Melbournians were “scared to go out to restaurants at night time because they were followed home by these [African] gangs, home invasions, and cars are stolen.”

His knuckle-dusting anti-China rhetoric, which dovetailed into the Beijing bashing relish of the previous Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, has also done wonders for his Labor opponents. Aston has more than 22,500 Chinese residents, which make up 14% of the seat’s population.

Then came Dutton’s cumbersome, post-mortem assessment of Victoria as a “very difficult market for us,” prompting Federal MP Julian Hill to retort: “No, we are 6.7 million Australians who overwhelmingly reject your extremist, divisive anti-science policies.”

Victoria, as a whole, has certainly returned lean pickings for the conservatives: 16 out of 38 seats in 1998; 14 out of 37 in the 2007 election that went to Labor; 12 out of 2010 when Julia Gillard held the reins as Prime Minister. Even with the Coalition victory in 2019, the Liberals won a mere eight seats.

Then came the fool’s optimist, the mandatory allowance for anyone riding into the valley of death. Enter the stumbly Liberal MP Jason Wood, in blithe ignorance, who insisted that Dutton’s face be plastered everywhere. “He’s a great guy,” he explained to Sky News host Chris Kenny, “we just need to get the public to know him a bit better and get him out and about meeting people.” The one problem with such views is that Dutton’s face is everywhere, ridiculed on Labor posters and pamphlets.

Some old hands of the party, disgruntled and seething, also offered their fill. Former Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, sticking to his increasingly tatty script, condemned his party for veering too far to the right, goose stepping to the tune of the Murdoch press and its conspiracy vendors. (Dutton had been the chief knife wielder in his overthrow.) “Victoria is a small l liberal state and the Liberal Party egged on by the Murdoch media has moved further and further to the right. The last time the Liberal Party went ahead in Victoria was in 2016 when Julia Banks won Chisholm.”

Dutton’s party increasingly cradles the prehistoric. He speaks to a dying demographic and beats the drum of mummies in sarcophagi lost in political lore. Such views speak to cemeteries filled with deceased ideologies and false gods. Short of a purge within the Liberals, or electoral suicide on the part of Labor—something known to occur from time to time—this will remain so.