“If you try to break the mold, you’re not going to last long,” famed linguist and cultural critic Noam Chomsky wrote in an essay published in Z Magazine in October 1997.

The essay, titled, “What Makes Mainstream Media Mainstream,” appeared before social media took off to the point it became essential to the formation of our modern culture.

Facebook arrived in 2004. A year later, YouTube was launched, followed by Twitter, now X.

With time, what may have started as creative or even juvenile digital phenomena became defining elements in our perception of ourselves, each other and the world at large.

Before the exponential growth of social media, the internet had numerous, but understandable, challenges pertaining to access, rules and regulations, financial viability, copyrights, social inequality and the like.

But none of this seemed to curtail our enthusiasm for the idea that the new media was rife with the kind of opportunities which would ultimately allow us to break free from the confines of mainstream media agendas, political selectiveness and outright censorship.

This makes Chomsky's article of 27 years ago particularly interesting. At the time, he criticized the “agenda-setters,” defined as the “elite media (which) set a framework within which others operate.”

The New York Times, for example, matters not just because of its content or the size of its readership, but the type of readers, the “privileged people,” who are wealthy "or part of something called the political class.” These are the “managers” of society, be it through government, corporations or media and academic circles.

Quite often, we are reminded of the few billionaires and their “Big 6,” the largest media companies that own most of the US media outlets. Many other countries follow the same logic of media control. Just imagine the sheer cultural and political hegemony that results from this skewed paradigm.

The truth is that most media organizations do not generally exist to tell the truth, but to tell their own truth, as in what they deem beneficial to their owners and their respective interests.

Back in the day, the hierarchy of information worked in such a way that large newspapers would create the standard narrative, according to which the rest of the media would be defined. Those to the right of the New York Times, for example, were the right-wing media. Those on the left were leftists, if not radical.

Thus, Chomsky's statement “if you try to break the mold, you’re not going to last long.” By “lasting long,” he was referring to those who wished to survive within mainstream media as a reflection of “obvious power structures.”

These kinds of limitations quickly allowed uncensored digital media, especially social media, to become a major source of alternative information and platforms for the exchange of ideas, political or otherwise.

The fact that it took governments a long time to decipher, let alone impose restrictions on the new phenomenon, allowed people the needed time to turn the initial digital chaos into a functioning system that brought peoples together beyond national borders, ideological polarization, cultural or religious backgrounds.

Censorship eventually caught up. But the early censorship was imposed on the social media platforms, not by the management of these platforms who, for years, continued to promote themselves as guardians of freedom of speech, fighting mainstream thinking, big government and oppressive regimes.

With time, things began to change, and disturbingly so.

During the early phase of the Covid-19 pandemic, Facebook was criticized for allowing “conspiracy theories,” as ideas suggesting that the deadly virus was “man-made.” Under heavy criticism, Facebook began censoring this kind of content, deeming it as falsehoods and fake news.

Only months after instituting a ban on these “falsehoods,” it backtracked, the Washington Post reported, alleging that, based on "ongoing investigations in the origins of Covid-19,” and following "consultation with public health experts,” claims as “man-made” virus will no longer be removed.

The decision was an outcome of political and business pressure, making Facebook operate the same way any mainstream media organization would behave, in the past or present.

If we apply the logic to many other heavily contested and censored topics, from Gaza to the Russia-Ukraine war, to US elections, to many others, we would realize that Facebook no longer behaves as a social media company, but an actual mainstream media organization with its own interests and agenda.

The difference between Facebook and New York Times is that, while the latter sets the agenda based on content it generates or commissions directly, Facebook sets the agenda based on user-generated content that it permits or bans. Unlike the New York Times over which we have little control, as Facebook users, many of us are unwilling participants.

This logic applies to all other major social media platforms, whether owned by Mark Zuckerberg, Elon Musk or any other.

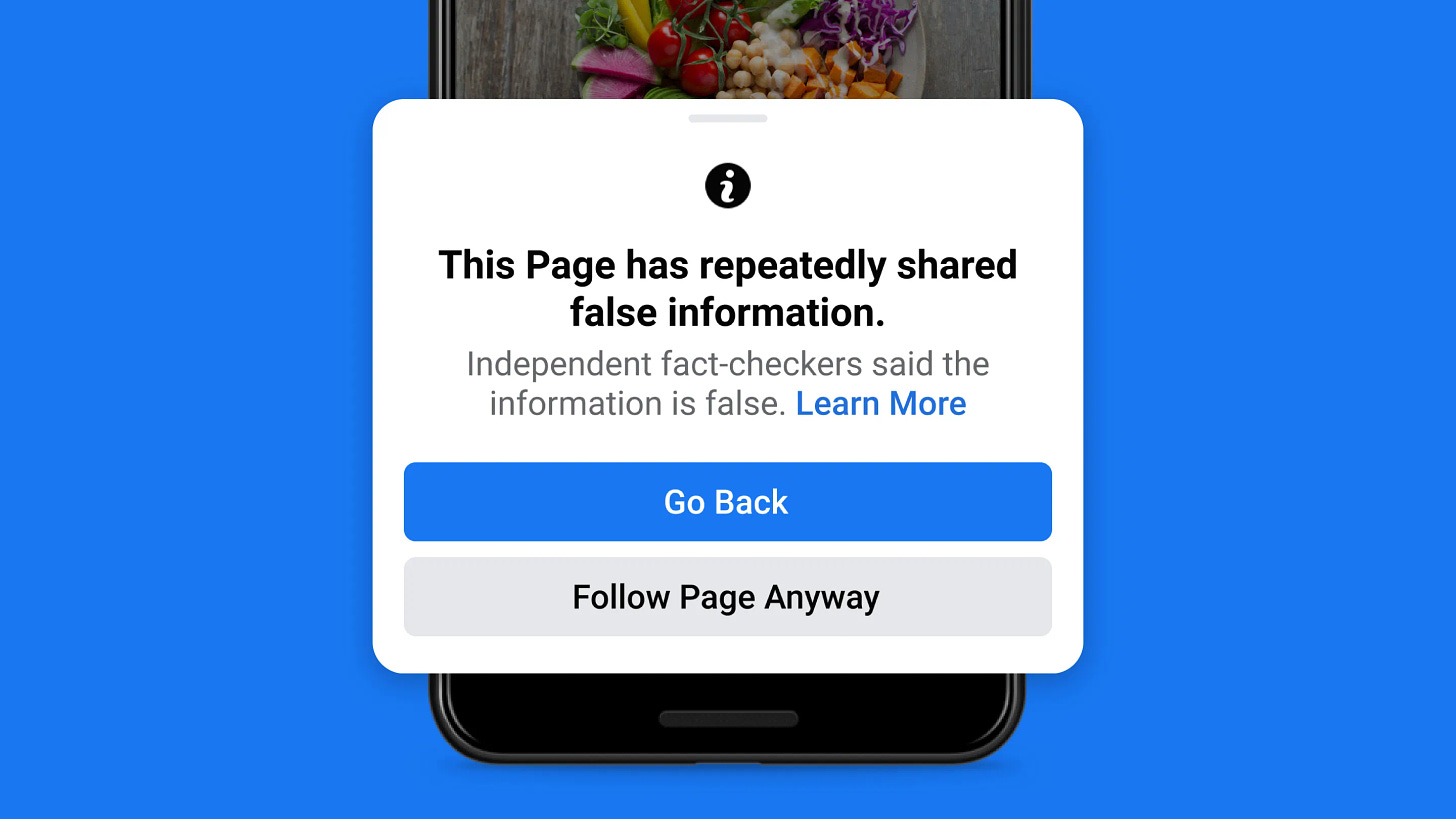

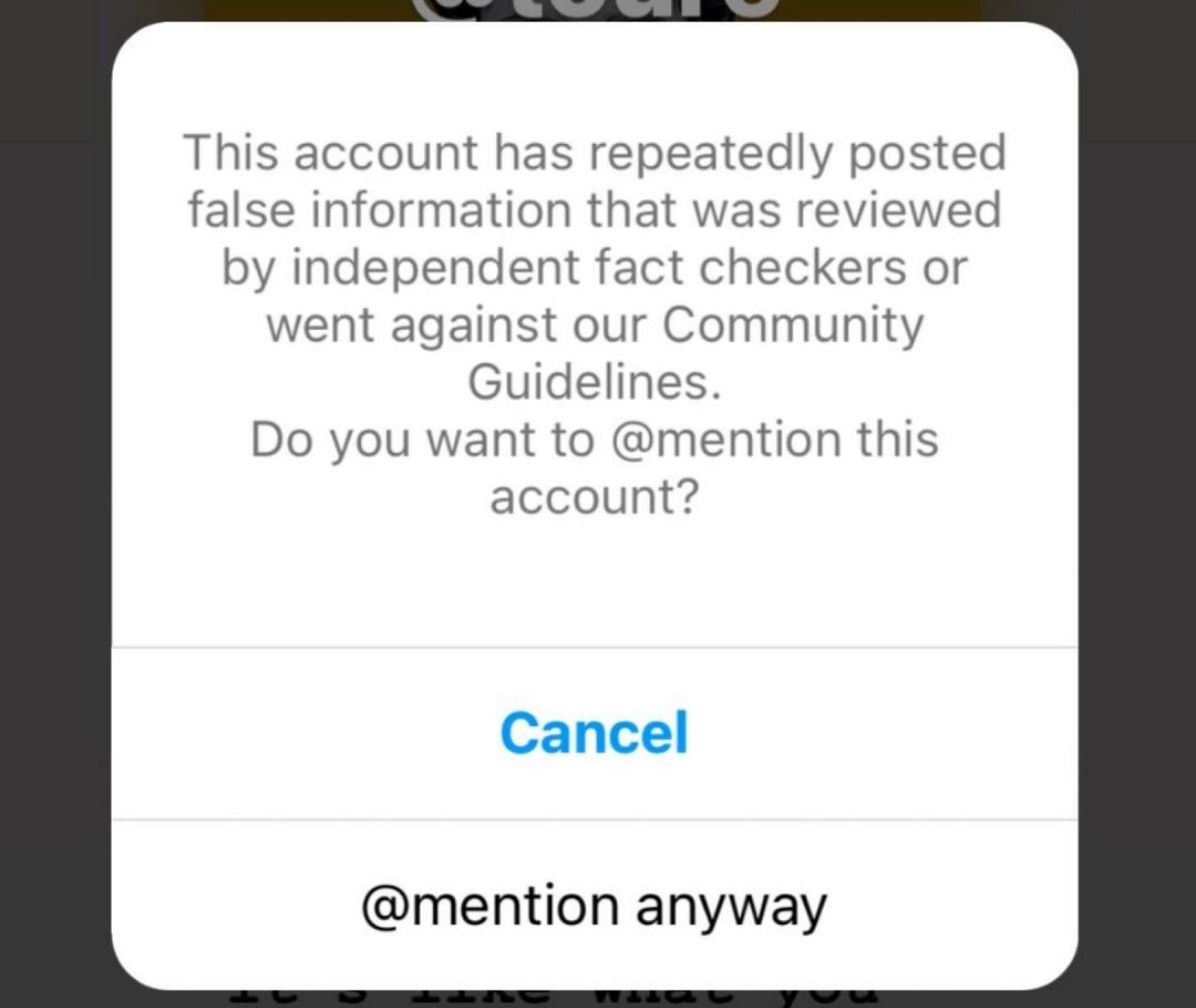

When I recently attempted to follow a user on Instagram, I received a note that asked me to reconsider my decision, since the company, or its “content editors,” have resolved that the person in question had disseminated what they deemed to be false information—or possibly the wrong opinion.

On LinkedIn or YouTube, posts are often removed if a certain number of people report them to the app administration, or editors, under whatever pretense. To reinstate the post, one would have to issue a complaint to justify his position.

In other words, social media platforms are replicating the old mainstream media behavior that controlled the flow of information since the invention of the printed press sometime in the 15th century. They are highly politicized, business driven, even ideological. They promote western interests, they care little for Palestine and they see western thought as superior to all others.

Though it will take more time for social media giants to find a permanent position with existing power structures, they will eventually get there.